The human right to be cold

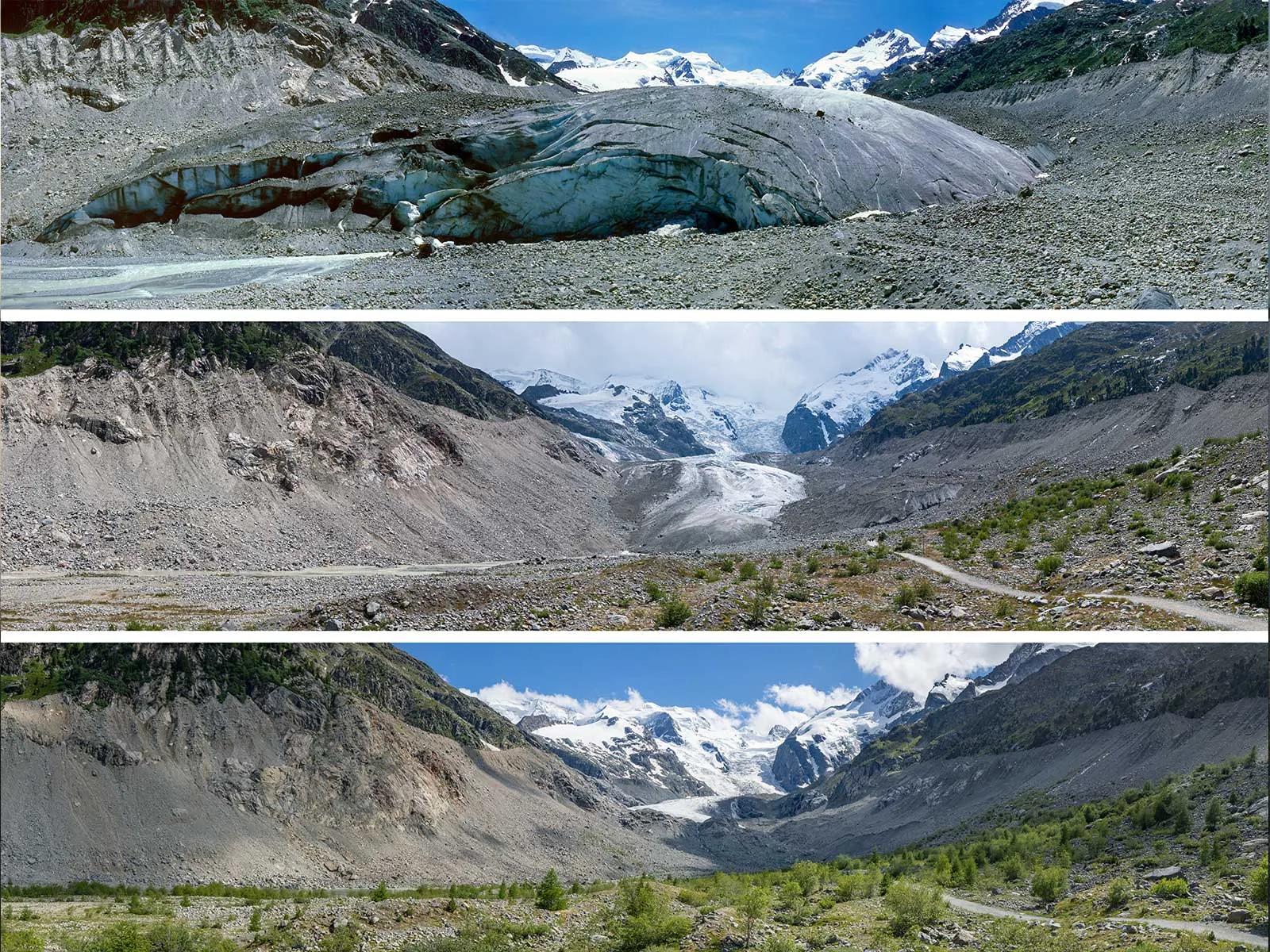

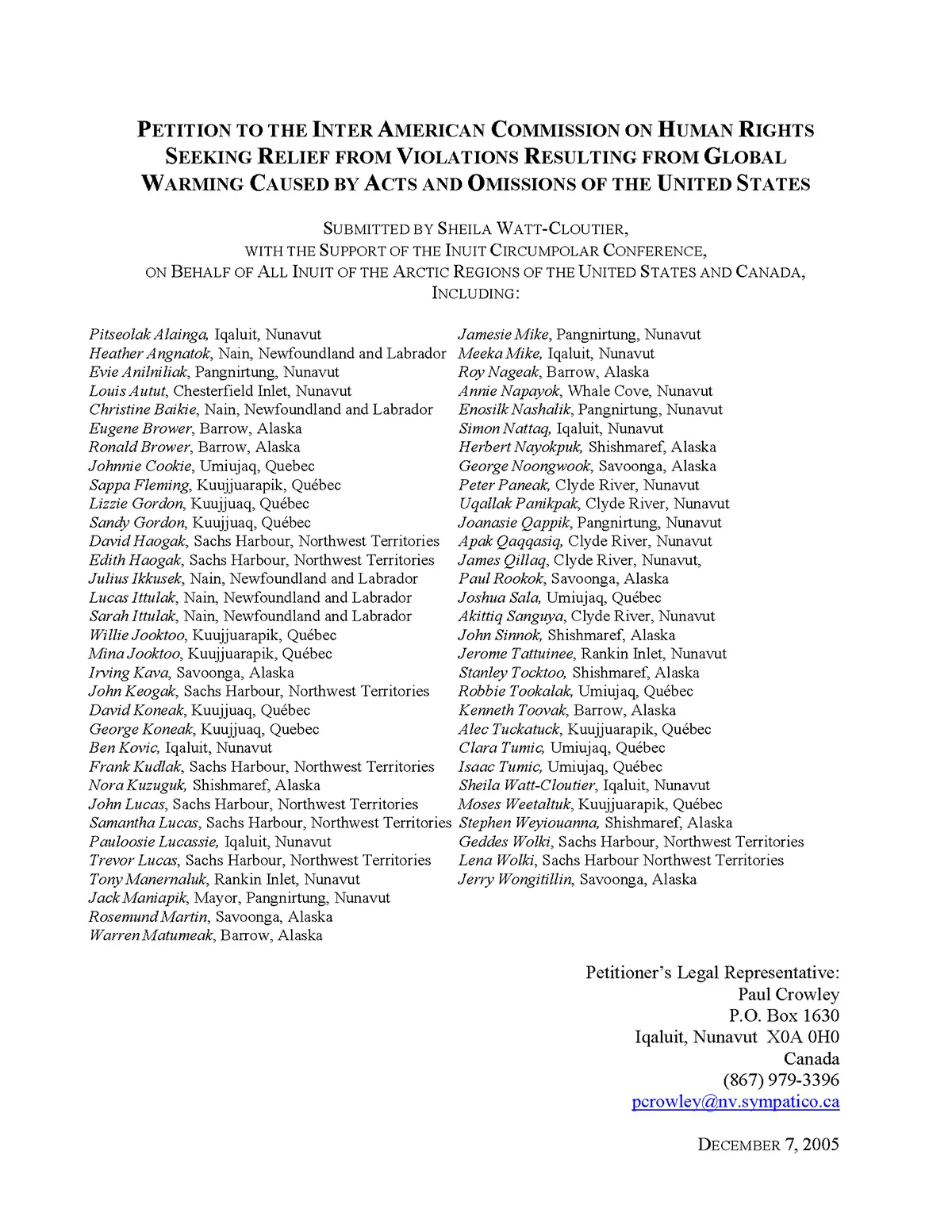

The climate-induced melting of Switzerland’s glaciers is not just an environmental issue, the legal implications are also huge. National sovereignty, the cornerstone of fundamental constitutional rights, is suddenly on thin ice (pardon the pun). Climate change impacts a whole host of international human rights. This raises the question of how we in Switzerland can guarantee the next global generation’s right to be cold irrespective of national borders.

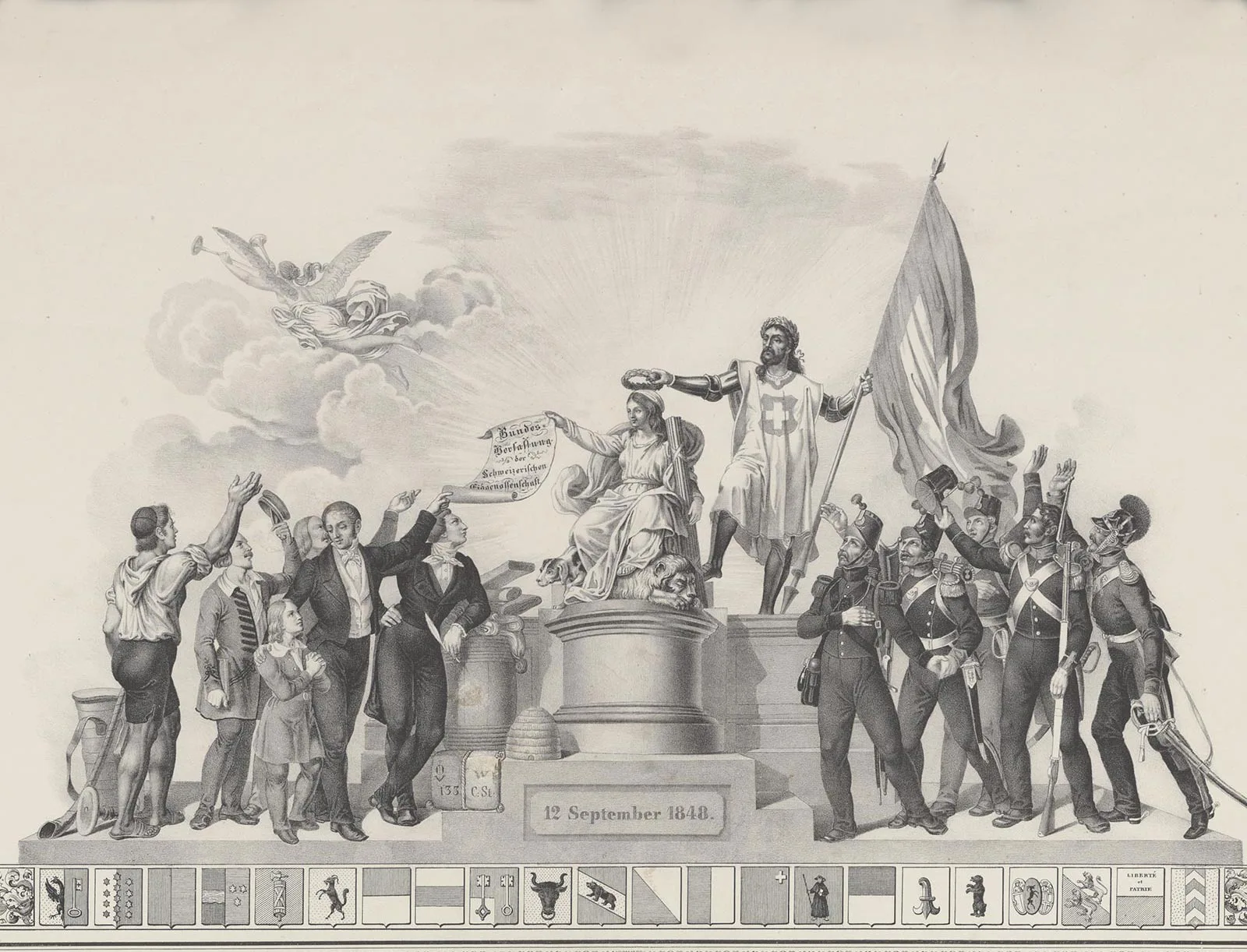

The Swiss Confederation is committed to the long term preservation of natural resources.