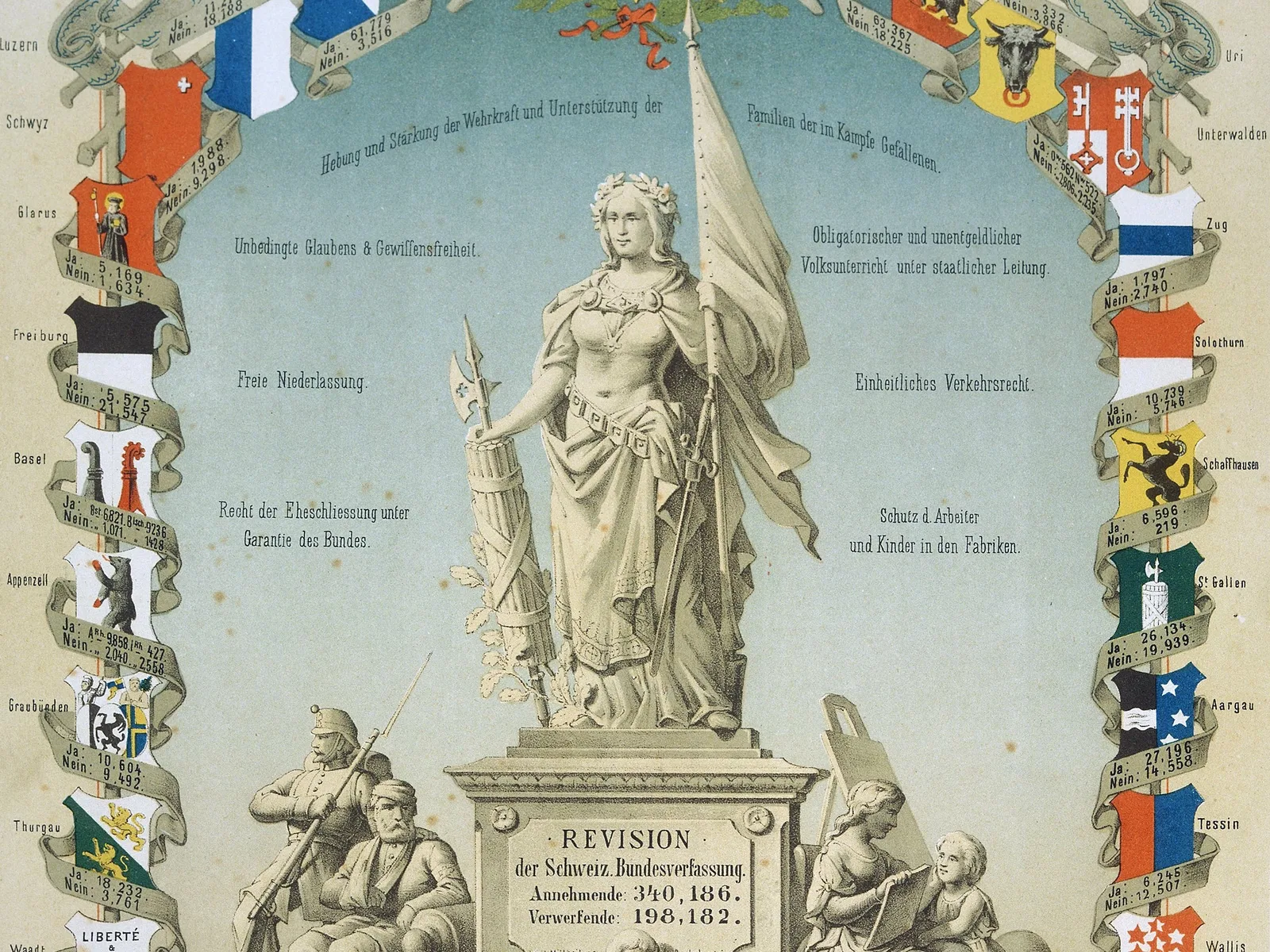

The Federal Constitution: helping ensure a fairer naturalisation process

The communes play a key role in accepting or rejecting applications for Swiss citizenship, which poses a risk of arbitrary or discriminatory decisions. The fundamental rights enshrined in the Federal Constitution serve as an important corrective.

![The stately room where the second-generation immigrant was subjected to questioning by the naturalisation committee in 1963. Her application for citizenship was turned down. The City of Basel authorities would later justify their decision by stating that "above all, [the candidate] does not have significantly strong ties with her adoptive country". Council Chamber at Stadthaus Basel.](https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/app/uploads/burgerratssaal.webp)

The Confederation shall regulate the acquisition and loss of citizenship by birth, marriage or adoption