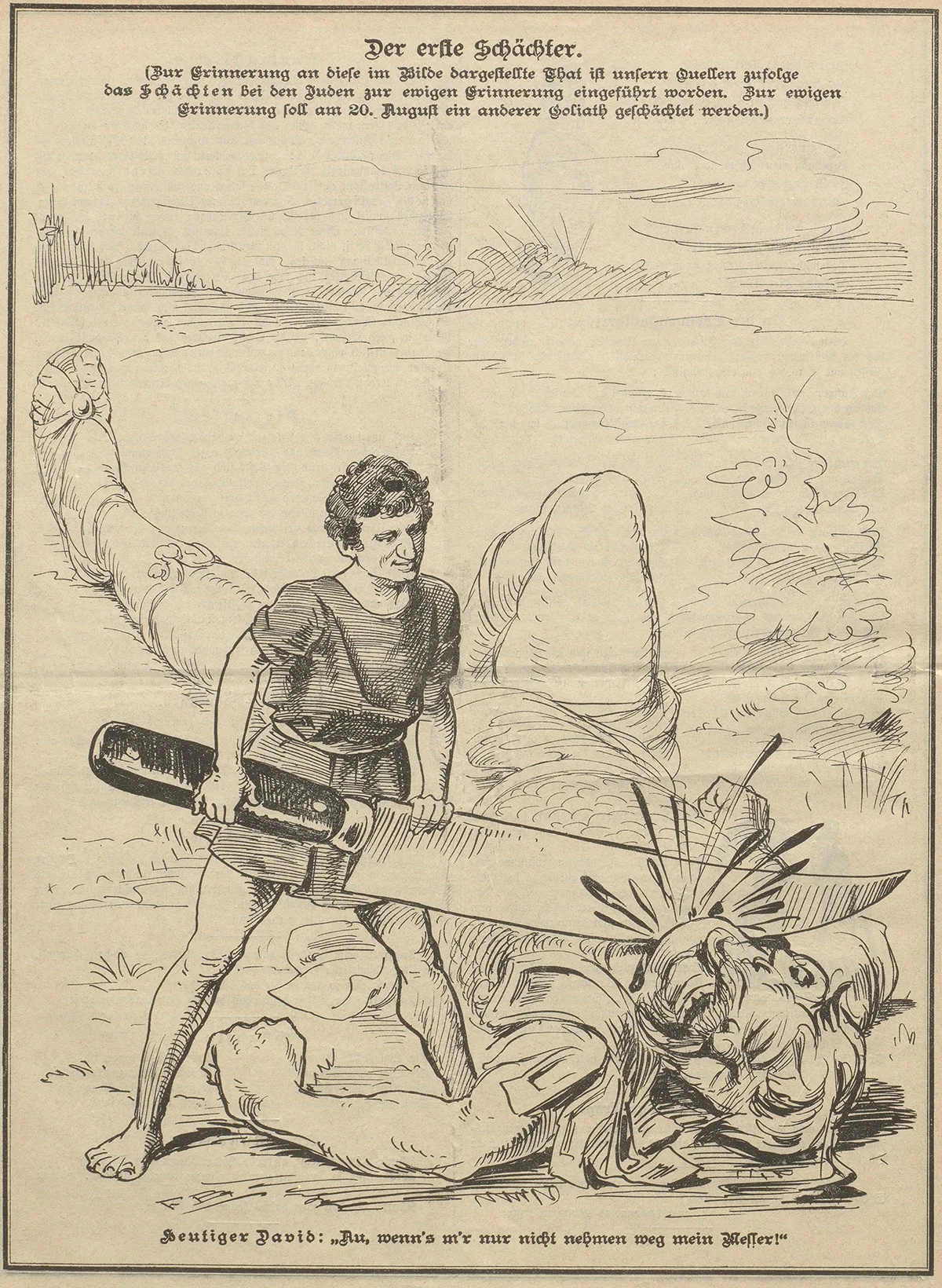

Switzerland’s rocky road to religious freedom

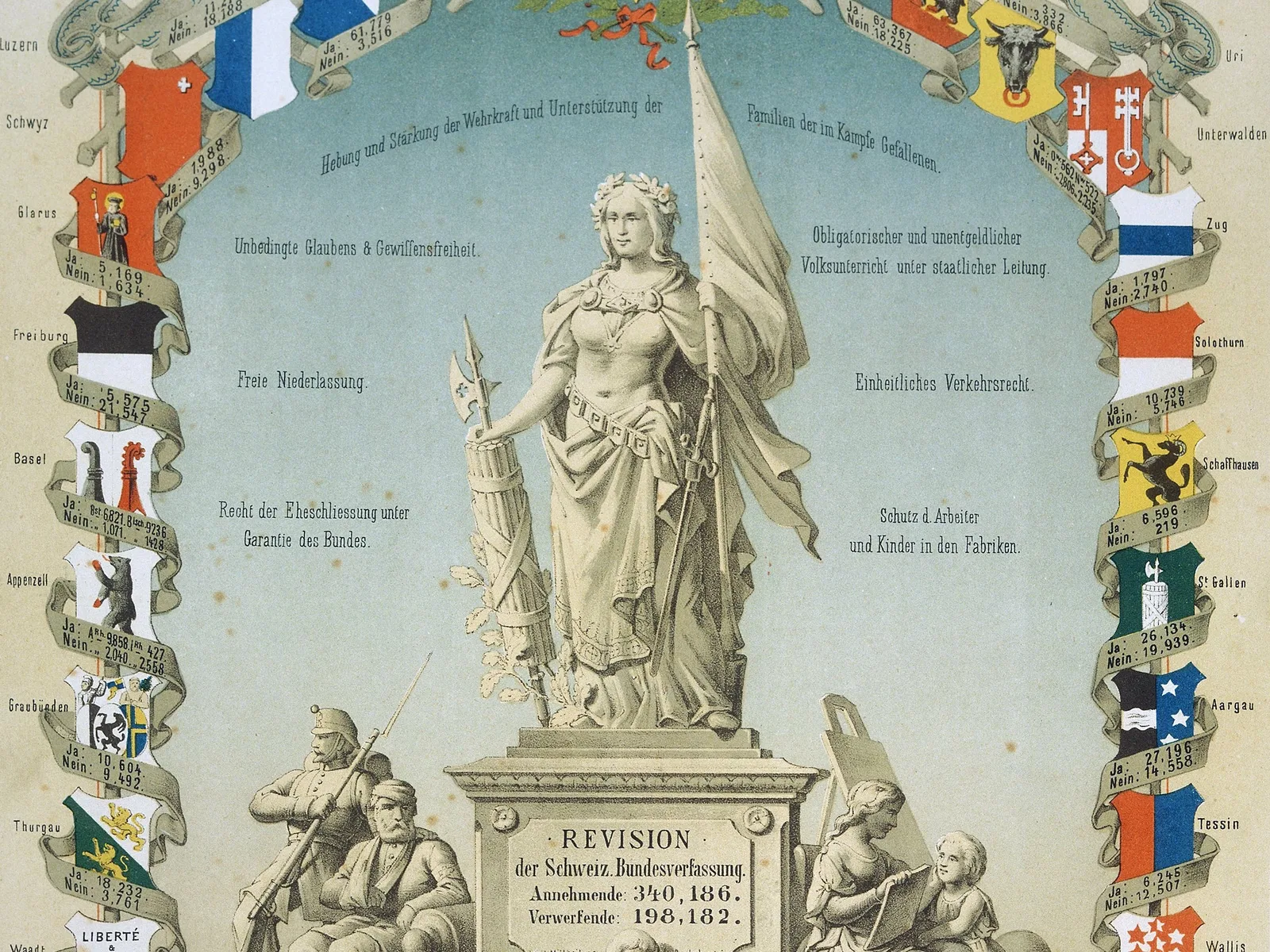

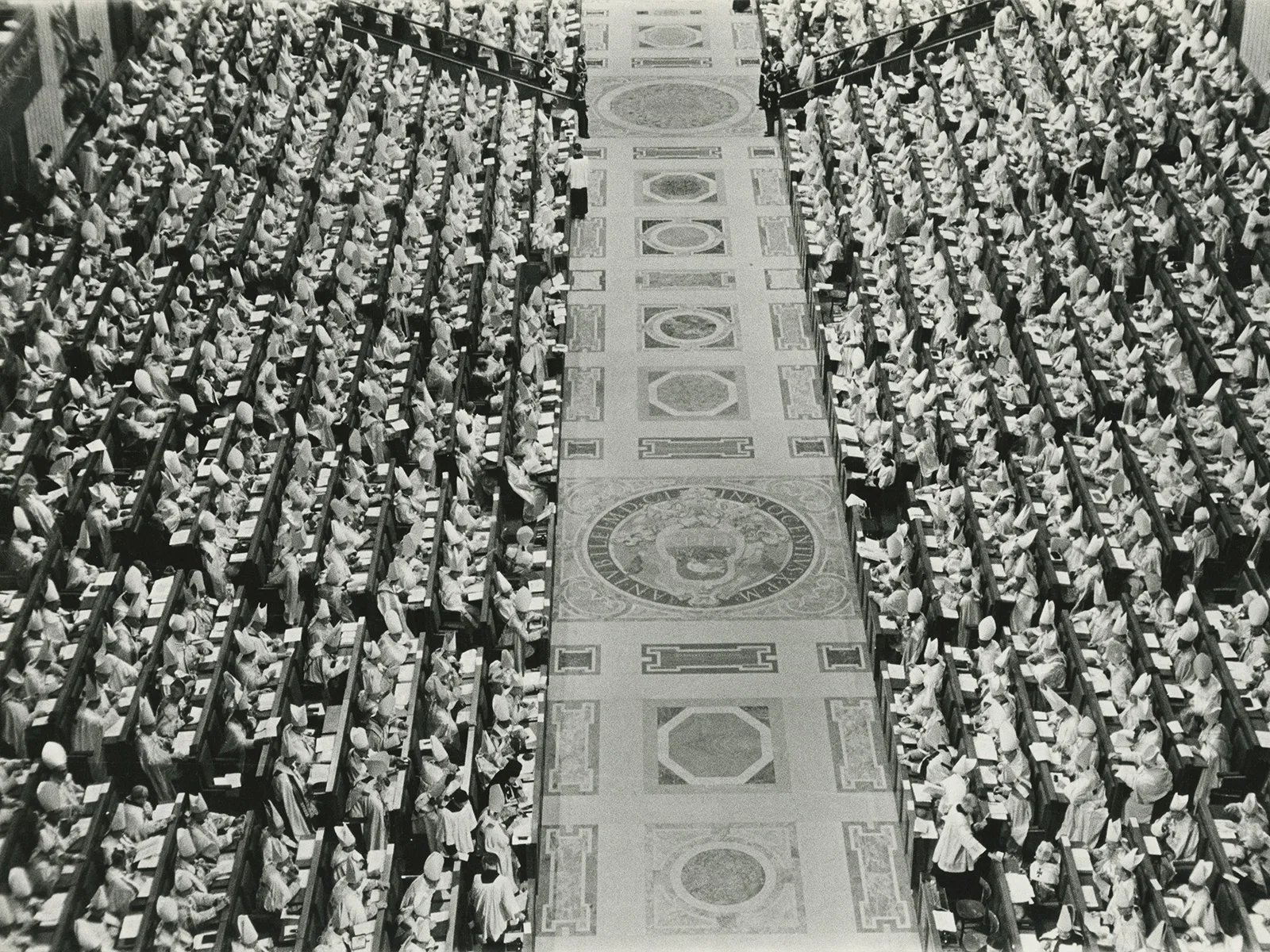

The Federal Constitution only became secular in 1874 when it granted religious freedom to the Jewish minority. In the current version, there are still two exemption clauses concerning Muslims.

Freedom of religion and conscience are inviolable.