Saluting one of the first Federal Councillors, Stefano Franscini

On 16 November 1848, the first Federal Council elections were held – a unique event in Europe at that time. The composition of the first national government is striking. And who wouldn’t have wanted to be friends with Stefano Franscini?

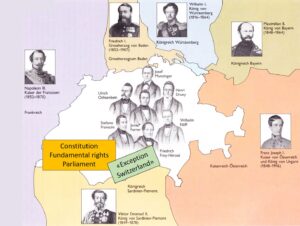

Revolutionary fire breaks out

Switzerland, a case apart

So that’s what you call federalism?

Centres. Margins. Unwritten laws

Federal Councillor Stefano Franscini. A passion for education and learning

One for all, but not all for one

And suddenly the penny drops

Liberalism born of enlightenment

![He holds a manuscript in his right hand, while his left rests on three books that embody his achievements: STATISTICA, [STORIA], ISTRUZIONE. Stefano Franscini monument in Faido (detail).](https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/app/uploads/stefano-franscini-statistica-225x300.jpg)