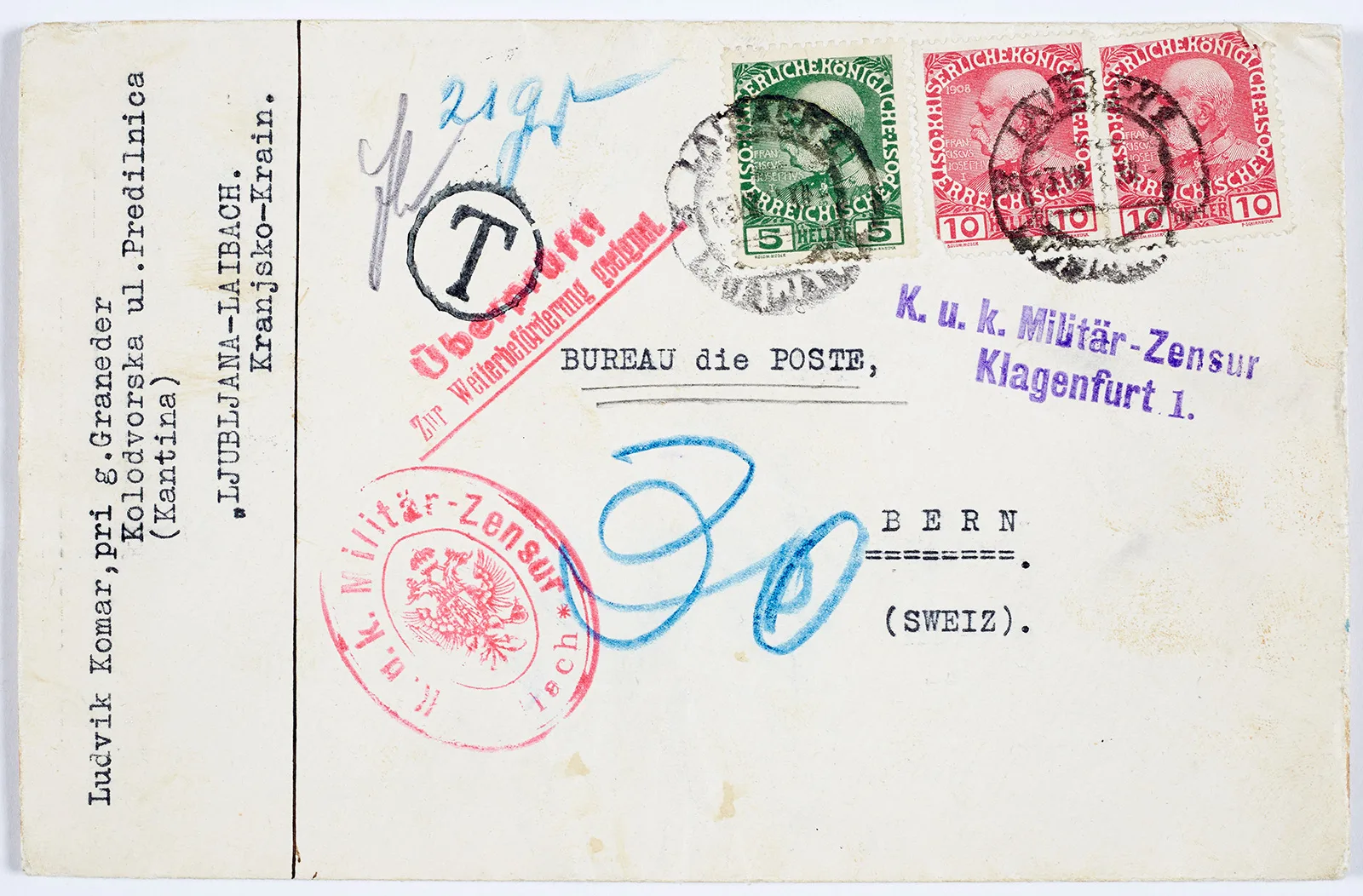

Privacy – a contested fundamental right

The Federal Constitution guarantees the right to privacy. Yet, time and again, this fundamental right has been restricted – in state security, the education system and taxation.

Every person has the right to be protected against the misuse of their personal data.