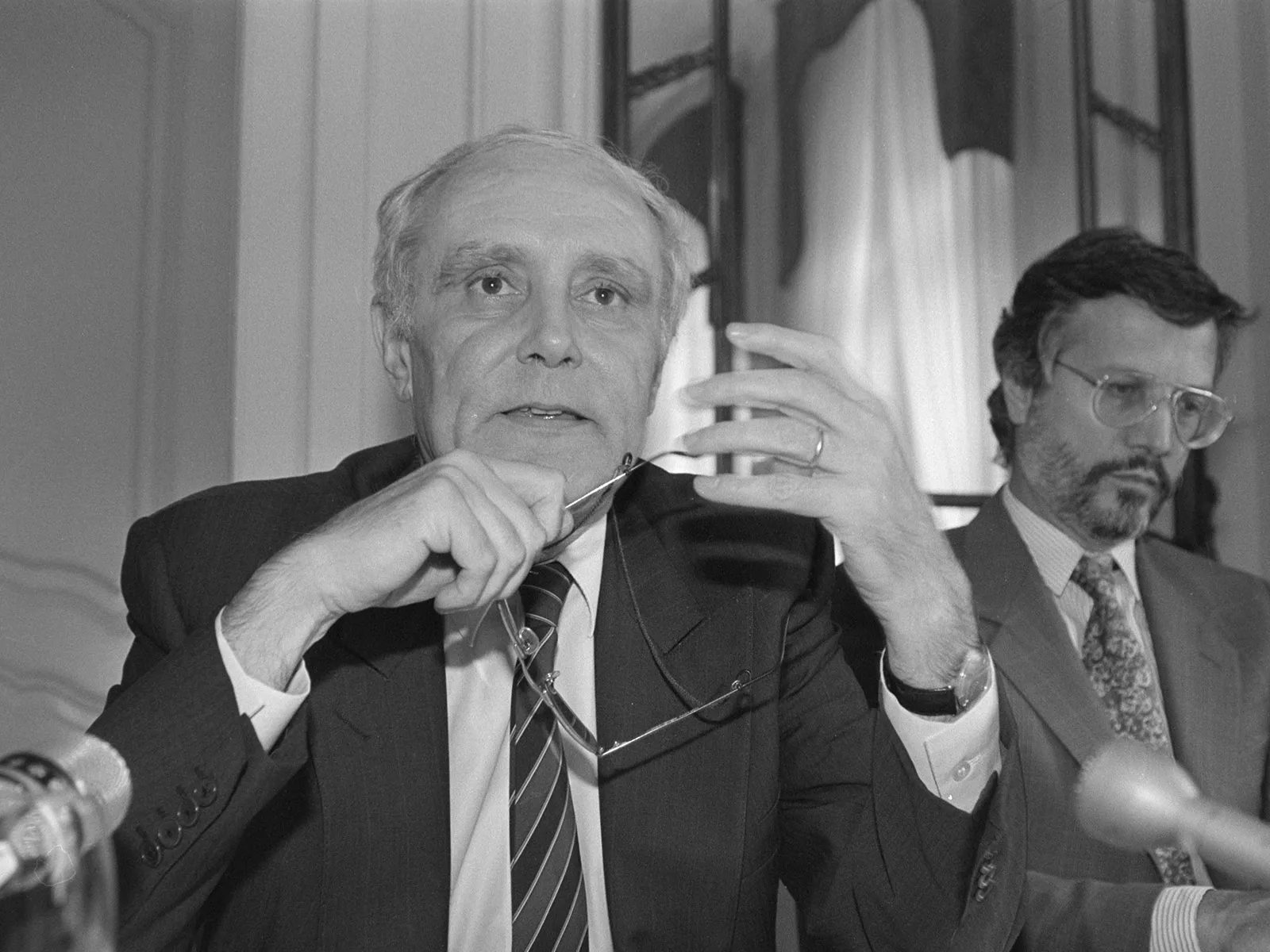

Ogi’s European charm offensive

In 1993, the Federal Council launched a charm offensive, fronted by Switzerland’s president Ogi, to pave the way for bilateral negotiations with the EU following the historic outcome of the EEA referendum of 6 December 1992.

EC or EU?

The European Community (EC) was formed in 1967 as an amalgamation of the European Economic Community, Euratom and the European Coal and Steel Community. The entry into force of the Maastricht Treaty on 1 November 1993 made the EC the main pillar of the newly established European Union (EU). The European Free Trade Association (EFTA) was founded by Switzerland and another six nations in 1960 as a reaction to the process of European integration. The European Economic Area (EEA) was originally conceived in 1989 as an umbrella covering the EC and EFTA. After Switzerland rejected the EEA Agreement and fellow EFTA member states Austria, Sweden and Finland joined the EU in 1995, its significance waned rapidly.

Adolf Ogi enticed François Mitterand to Kandersteg (in German). SRF

Joint research

This text is the product of a collaboration between the Swiss National Museum (SNM) and the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland Research Centre (Dodis). The SNM researches images relating to Swiss foreign policy in the archives of the Agency Actualités Suisses de Lausanne (ASL) and Dodis contextualises these photographs on the basis of official source material. The files for 1993 were published on the Dodis internet database on 1 January 2024. The documents cited in the text and other files from the volume Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland 1993 are available online.