Secret agents at Lake Geneva

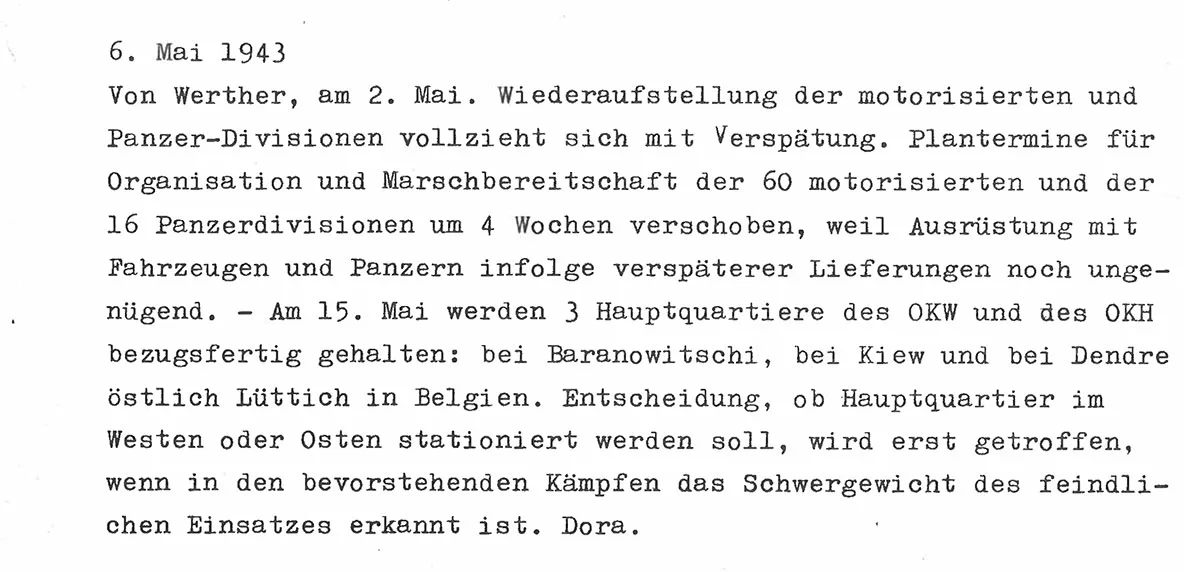

The Soviets received vital information from Switzerland during World War II. The spies of the ‘Red Three’ knew exactly what Hitler was up to.

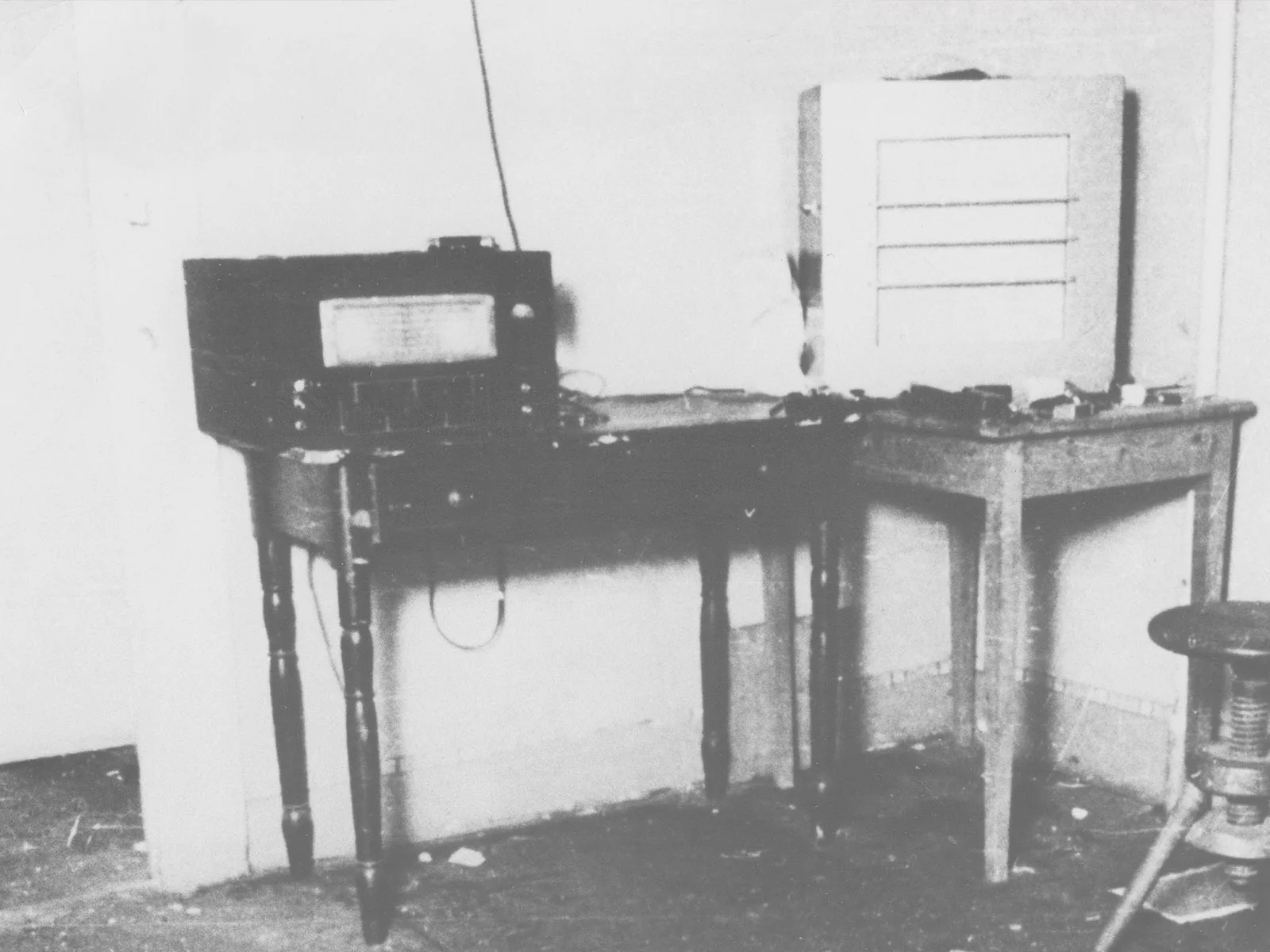

A chalet as spy headquarters

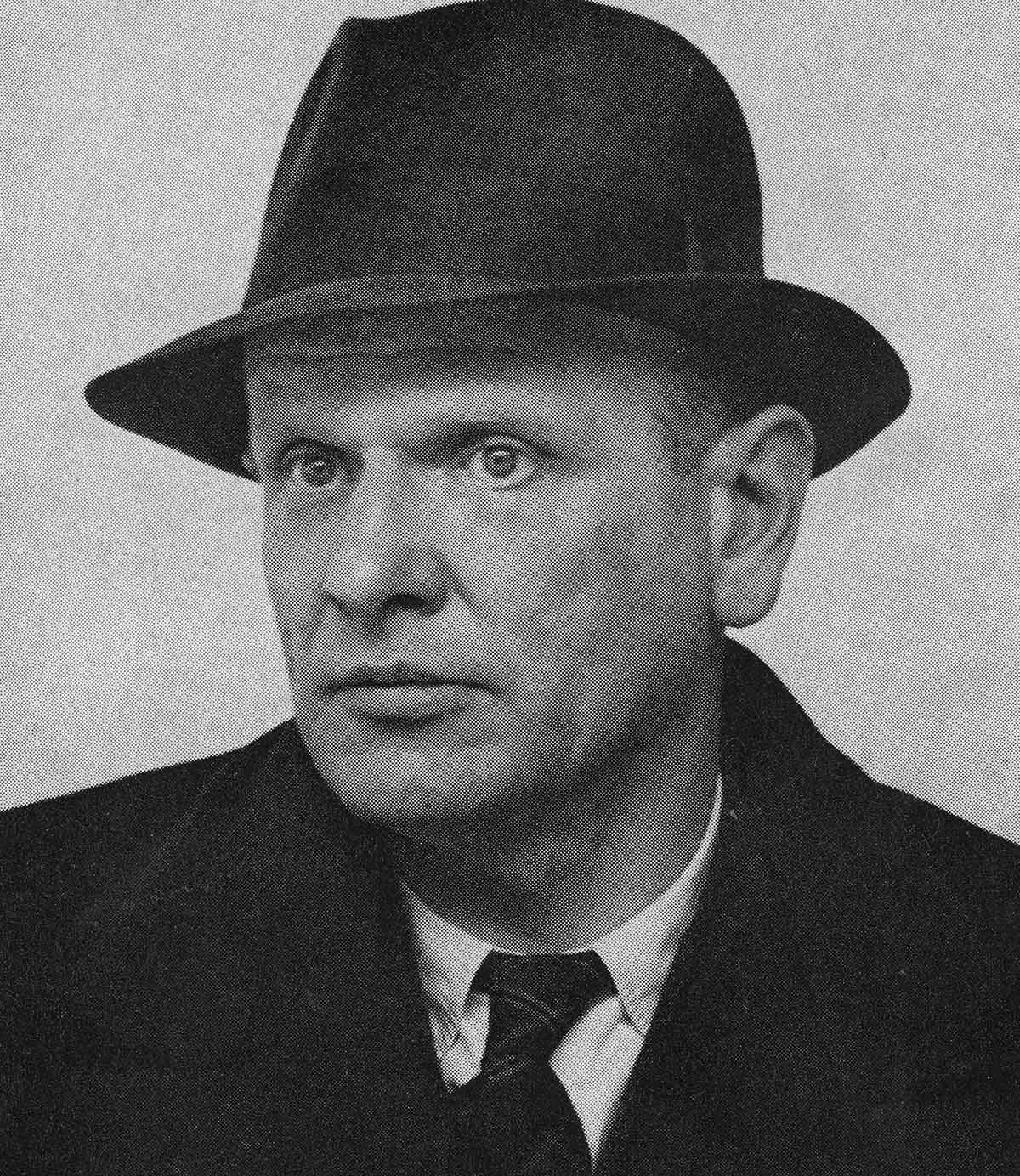

What happened to the spies…

Alexander Foote fled to Paris after Radó’s group was shut down. He was ordered to return immediately to Moscow. There, Foote was subjected to intensive interrogation (torture) to determine his loyalty and to uncover any potential double agent activity. After surviving the questioning, he was given a new identity as Major Granatov.

In Switzerland Sándor Radó was sentenced in absentia to three years’ imprisonment and 15 years’ expulsion from the country, in 1947. From his exile in Cairo Radó was taken by force to the Soviet Union, where he was promptly interned. Stalin later reprieved Radó, commuting his punishment to ten years in a labour camp. After serving this sentence, he was released in 1955 and returned to Budapest.

Rachel Dübendorfer was briefly jailed in Switzerland in 1944. In October 1945 a Swiss military court sentenced her in absentia to two years in prison. She fled via Canada to the Soviet Union, where she was imprisoned until 1956 and then released into the GDR.

Otto Pünter passed on important information to the Soviet Union via the Chinese legation in Bern before the Red Three group was terminated. After the Second World War, Pünter was President of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Bundeshausjournalisten (Association of Federal Parliament Journalists), and from 1956 to 1965 Head of Press and Information for the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation (SRG).

Margrit Bolli was sentenced by a Swiss military tribunal (Division Court 1A) in 1947 to ten months’ imprisonment on probation and a fine of 500 Swiss francs for intelligence activities against foreign states. Otto Pünter paid bail for her, and the radio operator was released.