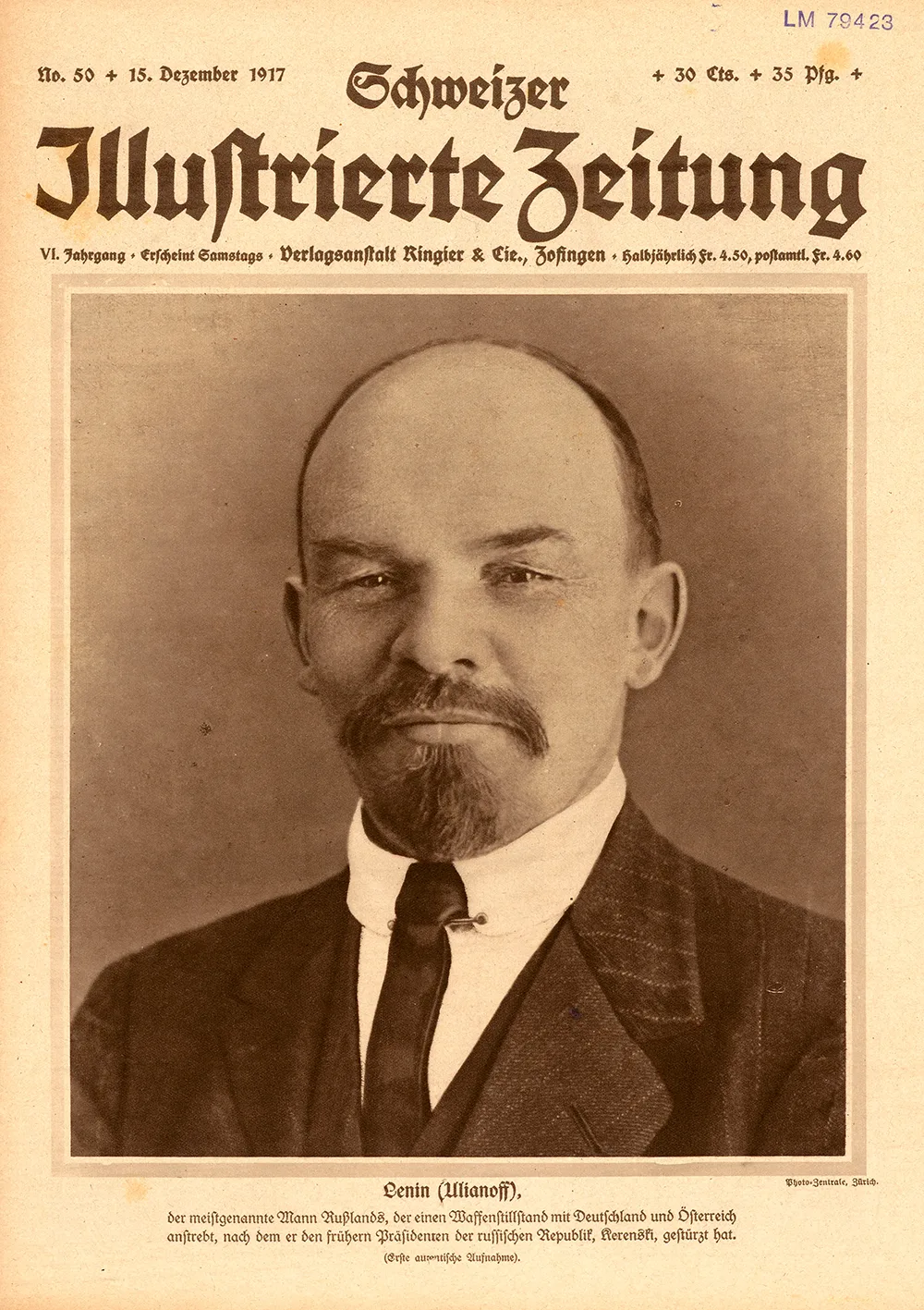

From Zurich’s backstreets to the centre of world revolution

Lenin’s explosive ideology, which would go on to shake the world, was partly concocted in Bern and Zurich. Yet he considered his Swiss comrades social romantics and opportunists.

Radicalisation in exile

At the end of his exile in 1900, he travelled around Europe to read, write and campaign, by now having adopted his nom de guerre, Lenin. In 1903 he went to Geneva, and then to Munich, where he published his manifesto What Is To Be Done? and made the case for a tightly organised vanguard party. He then went to London to continue his work, where he made the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ part of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party’s political manifesto, and positioned his radical Bolsheviks (‘the majority’) against the moderate Mensheviks (‘the minority’).

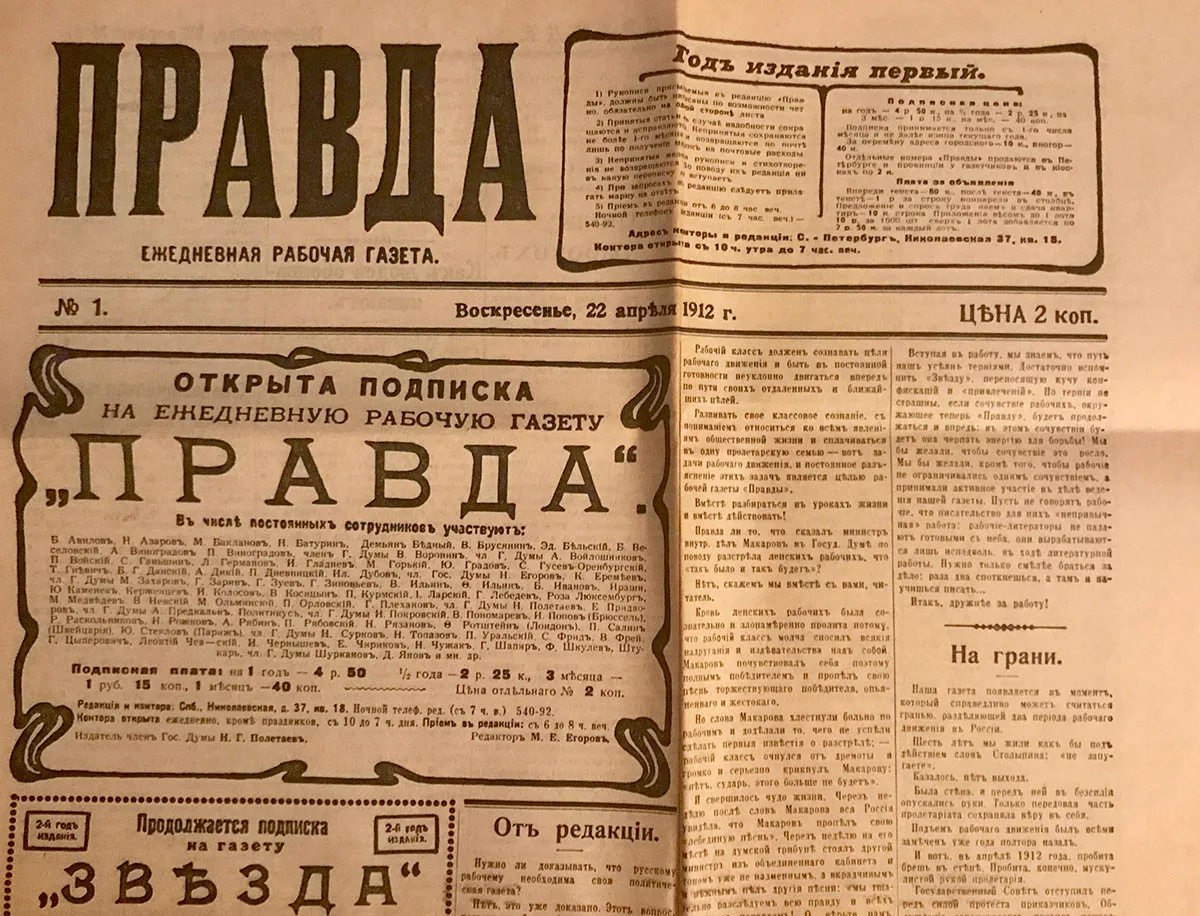

When the first Russian revolution broke out in 1905, he moved back to Russia, before fleeing to Finland in 1907 and then to Geneva in 1908. He worked from Paris for a time, turned up in Poronin near Krakow, and in 1912 helped launch the newspaper Pravda (meaning ‘truth’) while in exile. When the First World War broke out in the late summer of 1914, he was in Galicia in the Austro-Hungarian empire and immediately regarded as a hostile foreigner. In the end he was allowed to travel to a neutral third country.

“Soaked in petty-bourgeois dullness”

He had some trouble with the Swiss social democrats. Robert Grimm, the influential politician from Bern, engaged with him but rejected revolutionary violence and the notion of the proletarian dictatorship. Ernst Nobs, on the left of the party at the time, distanced himself from Lenin. Others, such as the National Councillors from the French-speaking part of Switzerland, Charles Naine and Ernest Paul Graber, shunned him. Outside of his small circle of followers, he was seen as a “hopeless, obsessive sectarian” and as a “mischief maker and oddball”. Conversely, he considered his Swiss comrades to be pacifists and tame opportunists.

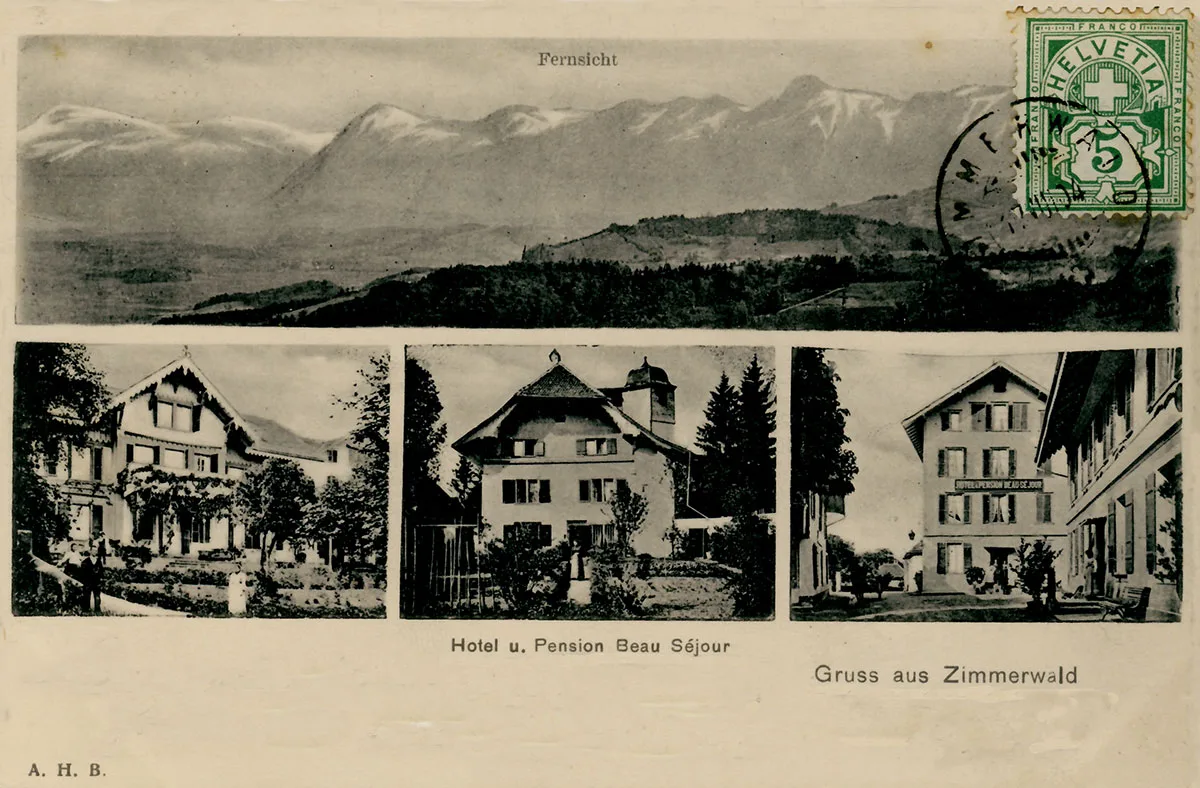

Under the guise of an ornithology society in Zimmerwald

Lenin failed to win much support with his calls for civil war, both in Zimmerwald and at the subsequent conference in Kiental in 1916. However, his star was rising among revolutionary socialists elsewhere in Europe. From then on he called his movement the ‘Zimmerwald Left’, which was synonymous with Bolshevism. Trotsky, who sided with Lenin, later wrote: “In Zimmerwald, Lenin was tightening up the spring of the future international action. In a Swiss mountain village, he was laying the cornerstone of the revolutionary International.”

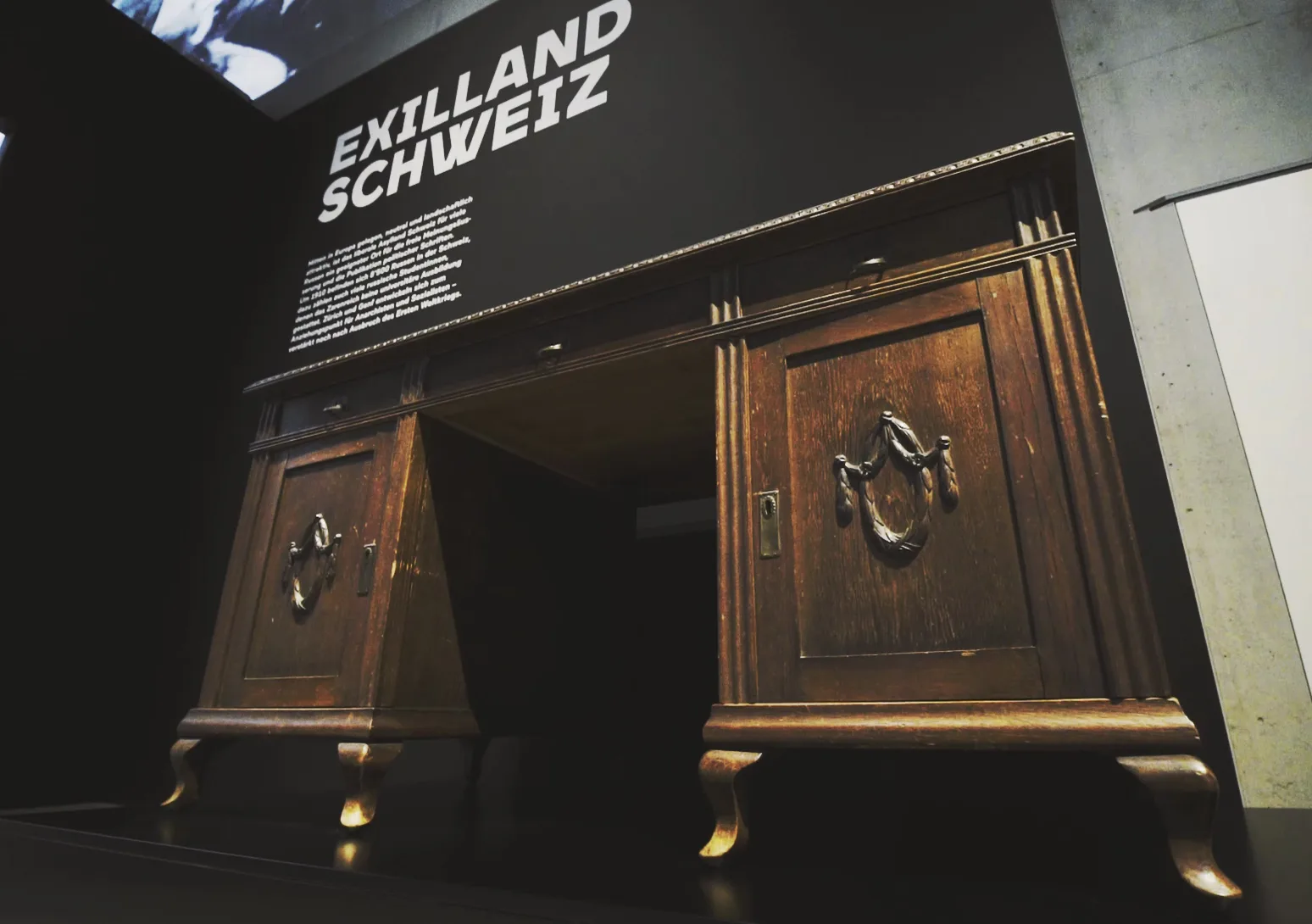

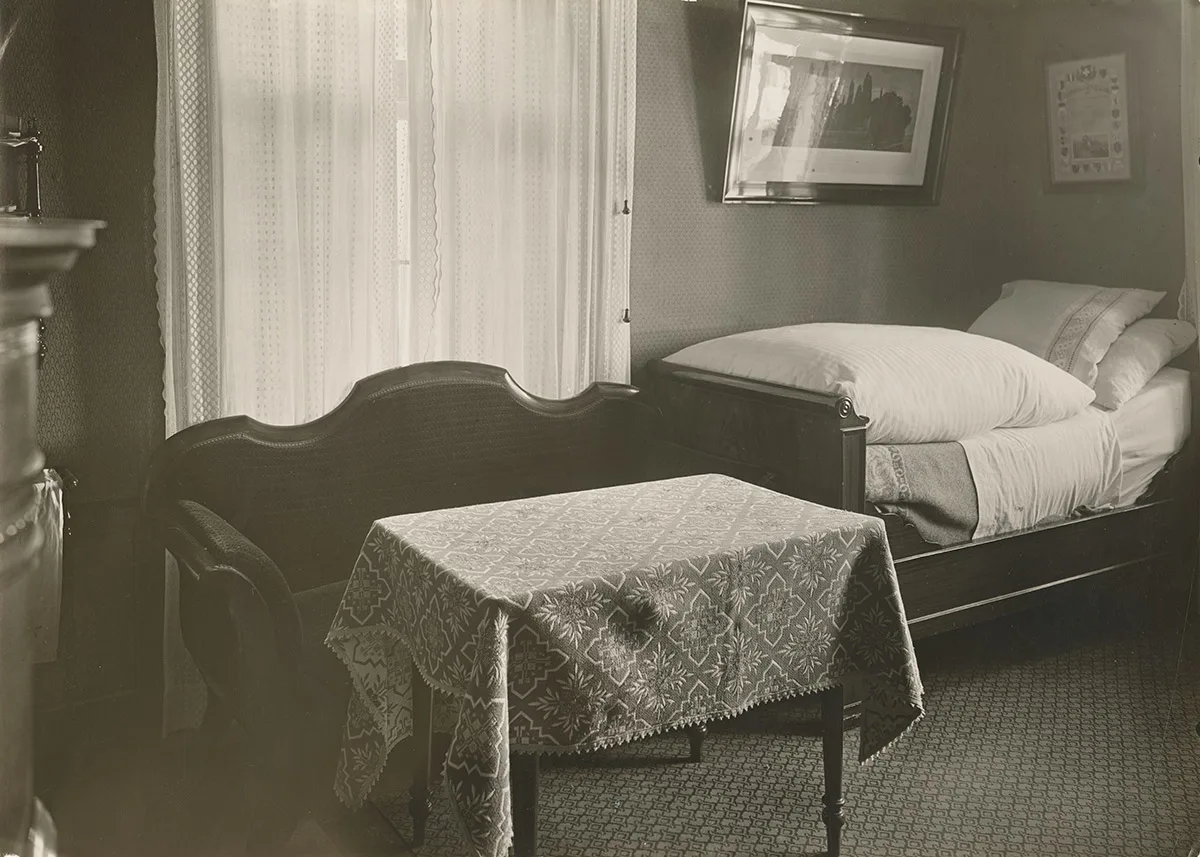

An explosive theory made in Zurich

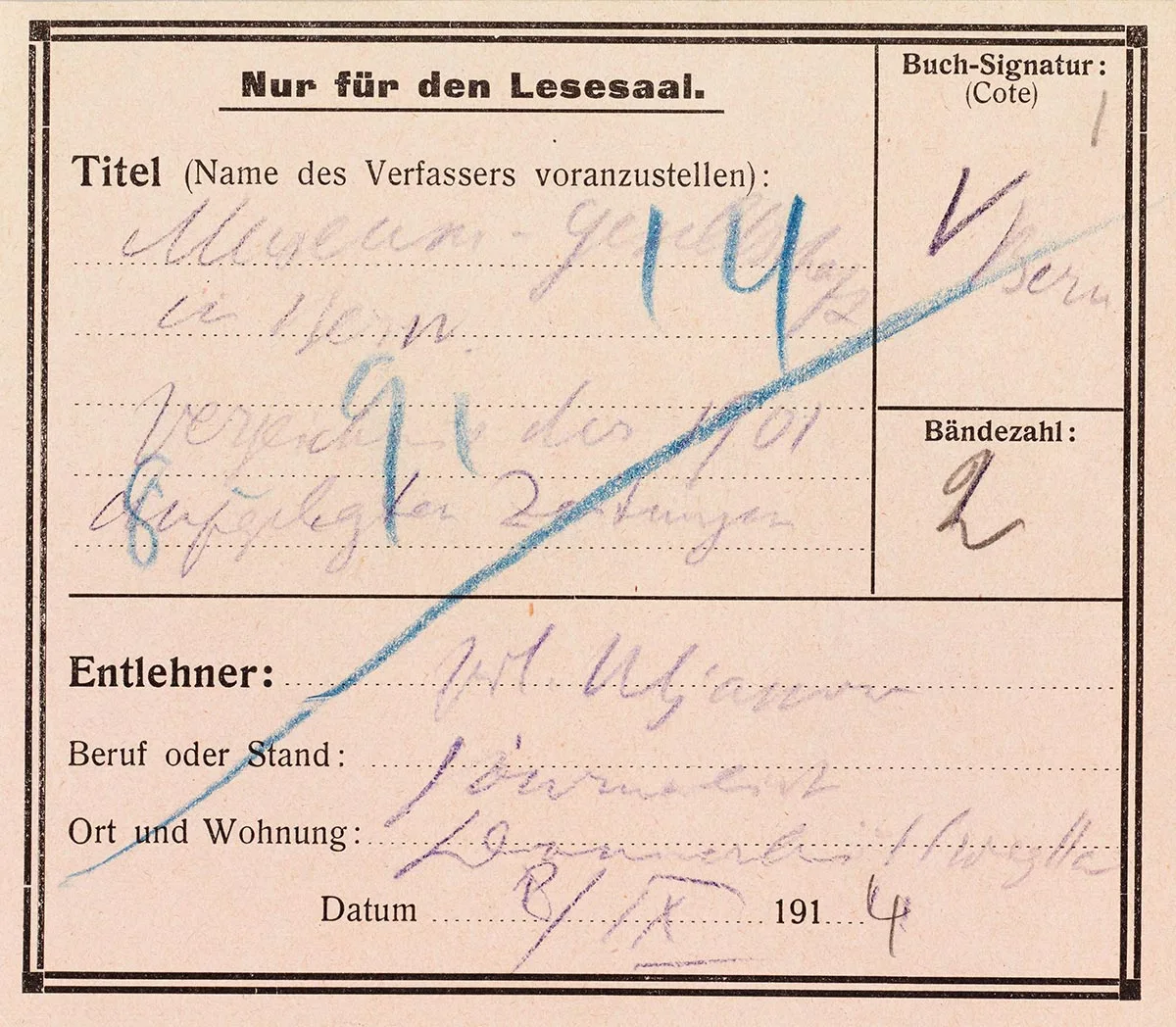

Lenin was incredibly disciplined, working from morning to evening at the Zentralbibliothek, at the ‘Swiss Social Archives’ on Seilergraben, at the Museumsgesellschaft reading society on Limmatquai, and at the Eintracht union building at Neumarkt. Historian Willi Gautschi considers his book Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, which was published in August 1917, as the “authoritative intellectual weapon of world communism in the battle against the capitalist social and value system.” He says that Lenin penned nearly all the fundamental works on which Bolshevism is based in Switzerland. “It’s no exaggeration to say that the intellectual explosive that was detonated in the October Revolution was made by Lenin in Switzerland and dispersed from there by his supporters.” The Russian dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who himself spent two years in Zurich in the 1970s, also sees Lenin’s period of Swiss exile as “the crucial years in which he laid the groundwork for the Soviet state”.