Swiss on the Titanic

Over a century after her dramatic demise, the Titanic lingers omnipresent in the human imagination. The stories of the Titanic’s Swiss staff and passengers are a rich kaleidoscope into a maritime disaster and an era on the precipice of tremendous change.

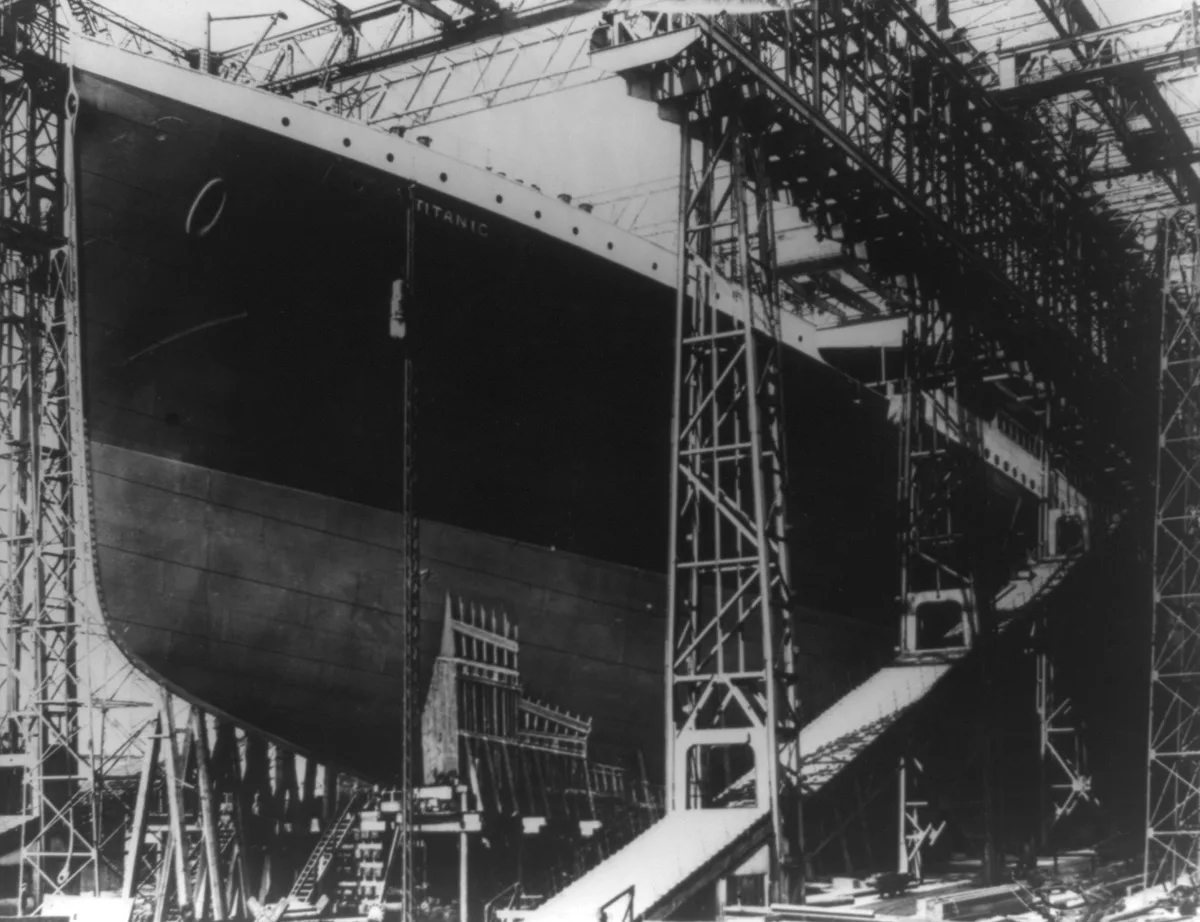

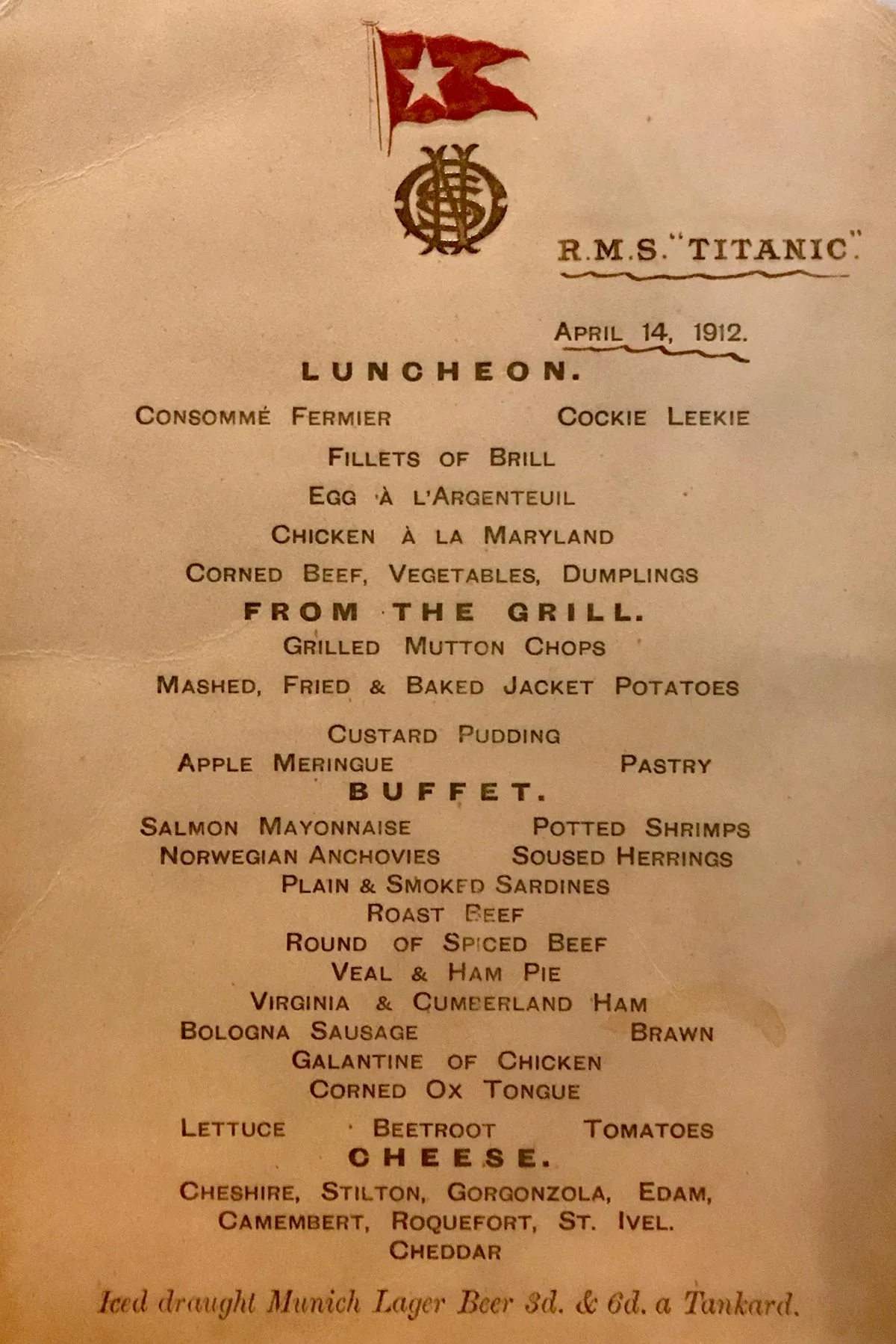

The first of a trio of new ships, the Olympic, was launched in 1910 and sailed on her maiden voyage in 1911. As the largest ship in the world and the first in a new class of superliners, the Olympic was a marvel, receiving international acclaim. From her exquisite first class cabins to her gymnasium, and from her Veranda Café and Palm Court, the Olympic dazzled travelers. The Olympic’s second and third class accommodations even received accolades.

The Titanic’s Swiss staff

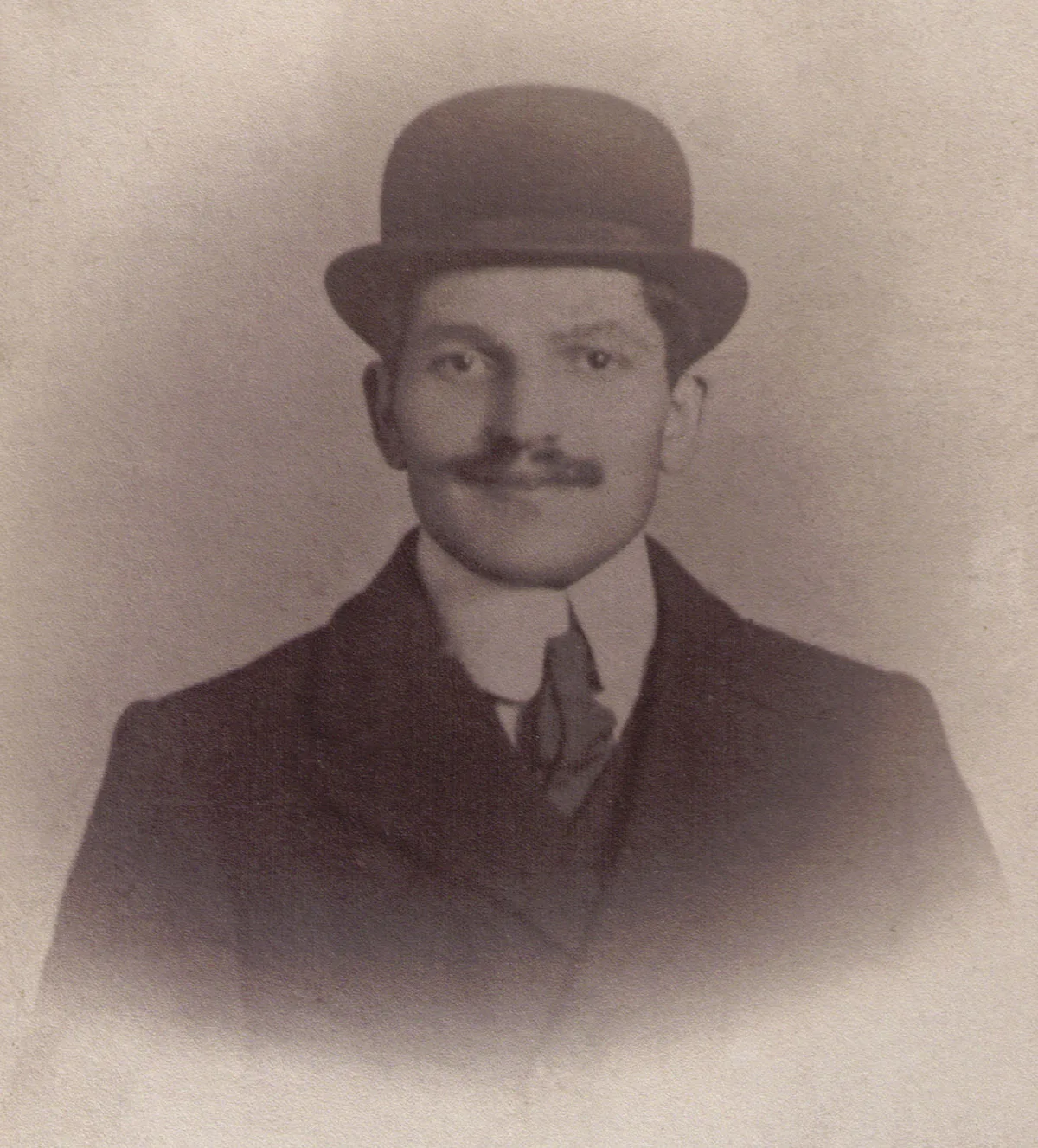

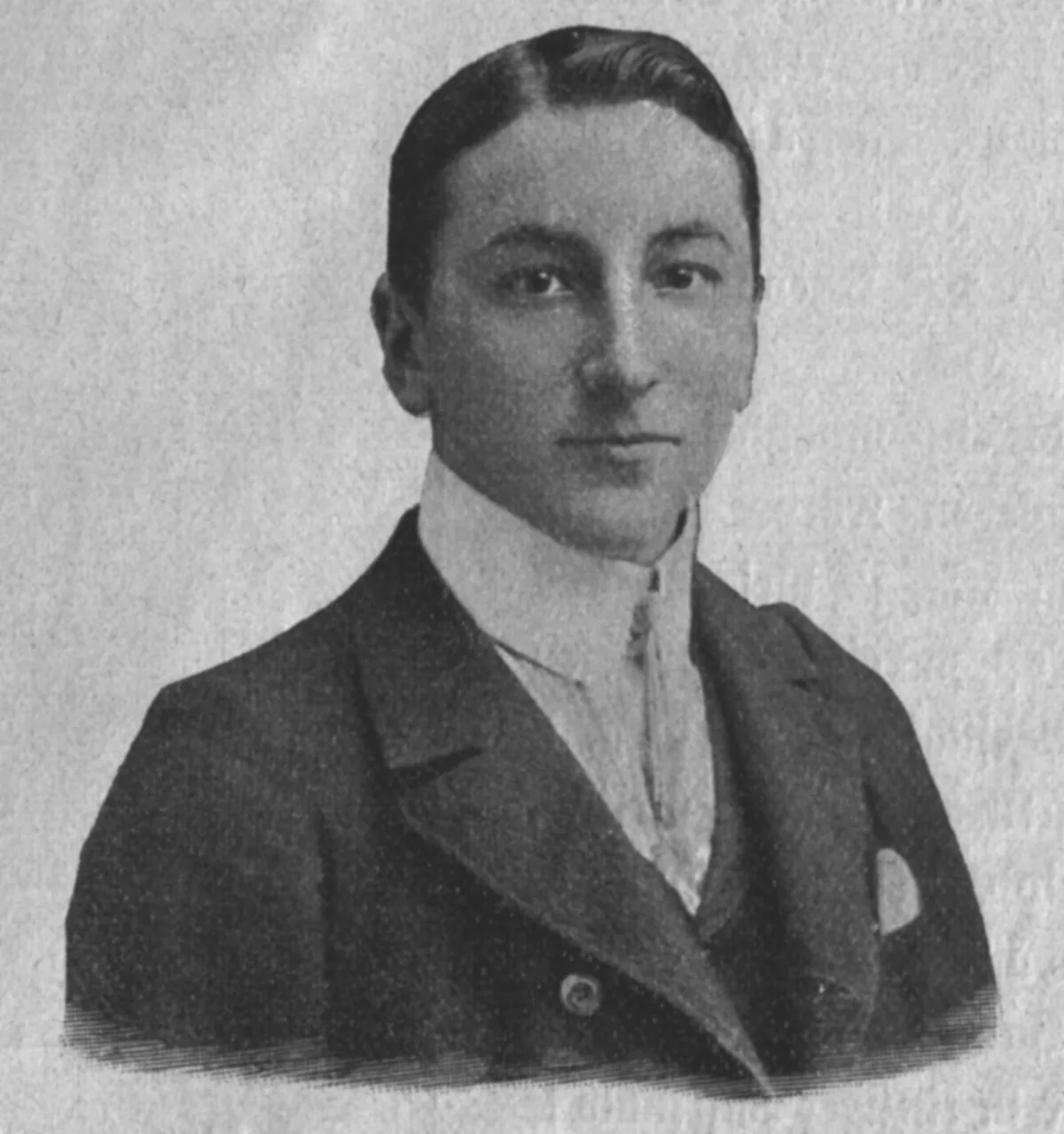

Like Emma, Adolf Mattmann was focused on the future. Adolf was born in Inwil (LU) and trained as a confectioner at the renowned Karl Häberle pastry shop in Luzern. Fluent in French, German, and English, Adolf believed he could capitalize on his talents and receive higher wages if he moved to England. He emigrated in 1911 and obtained a work contract for the Olympic. Adolf then transferred to the Titanic in April 1912 – where he would serve as a glacier – but the new contract was temporary. His long-term goal had been to work at a grand hotel in London; he was hired by one only weeks before the Titanic’s departure.

Titanic’s Swiss passengers

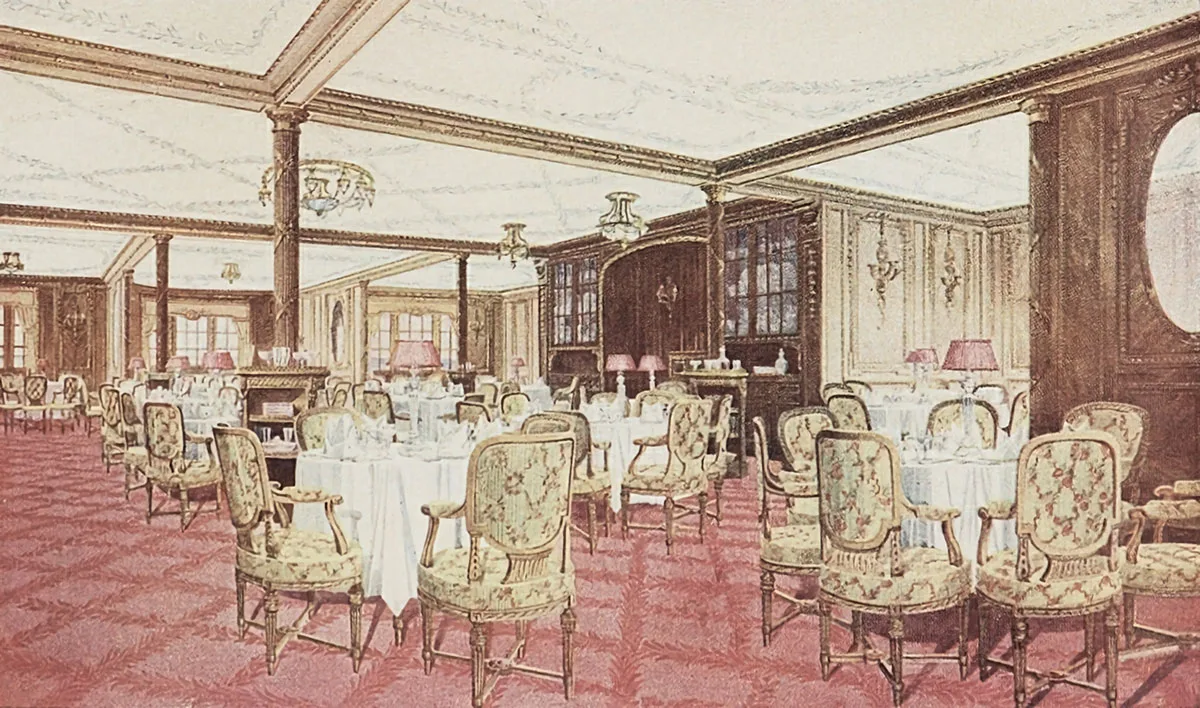

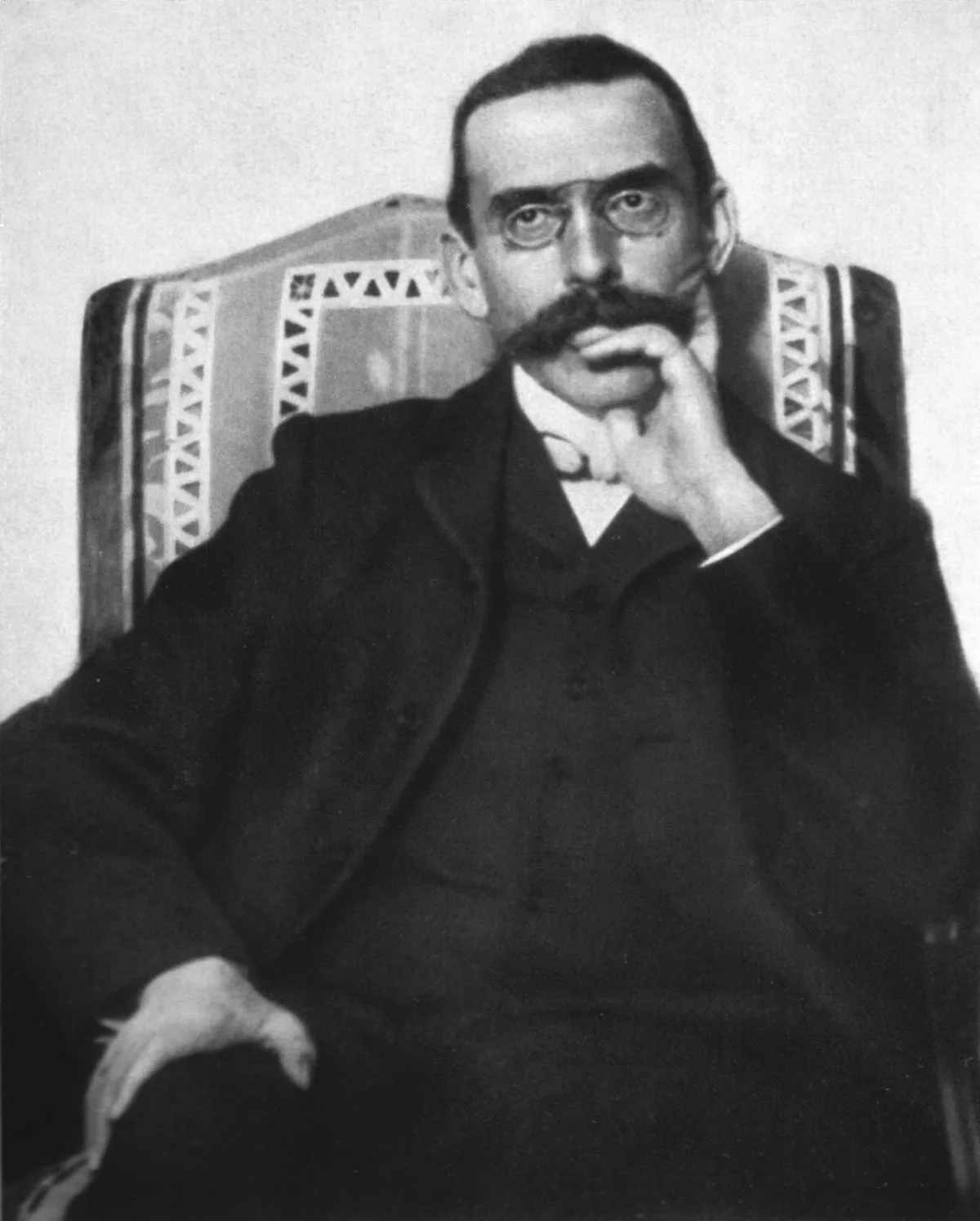

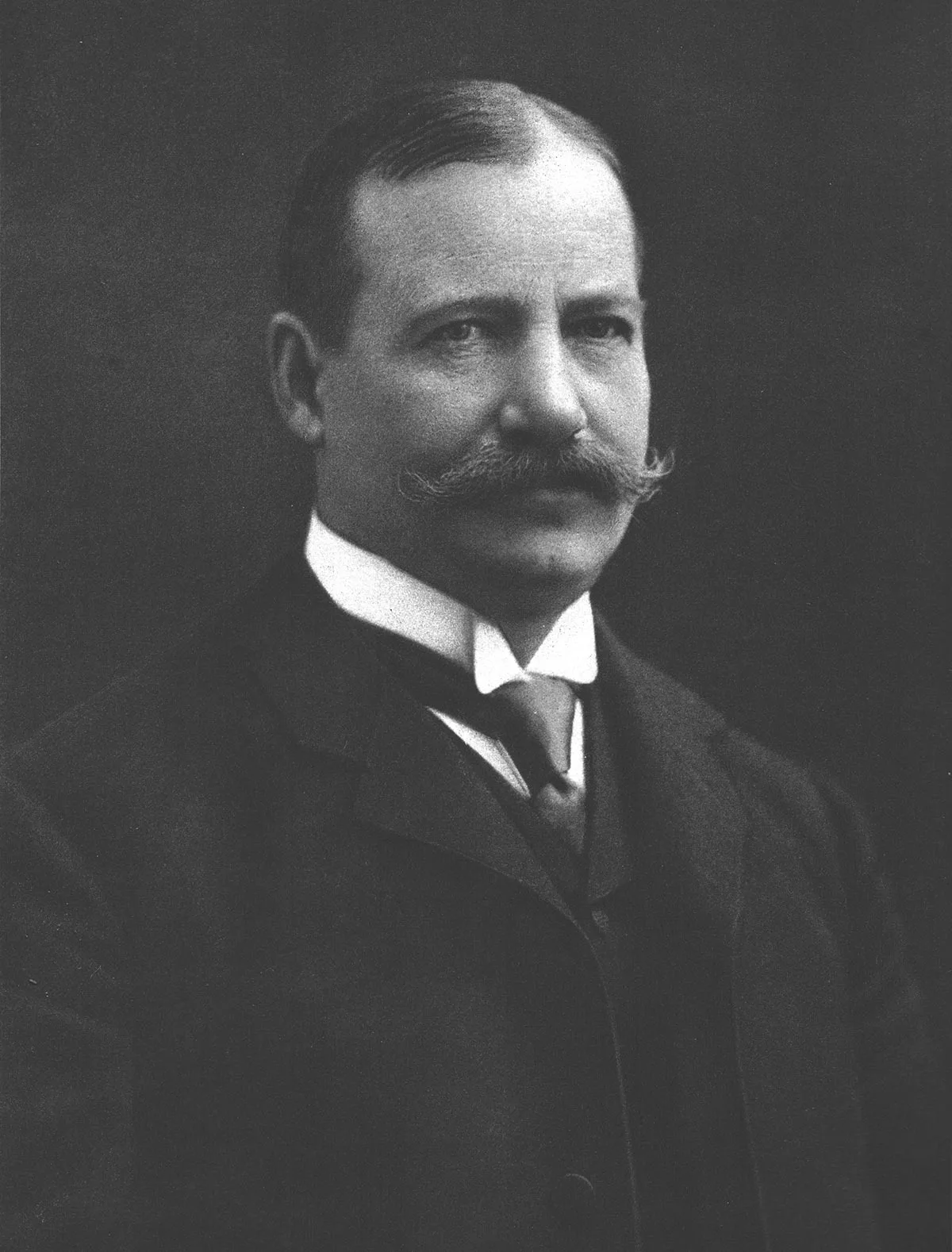

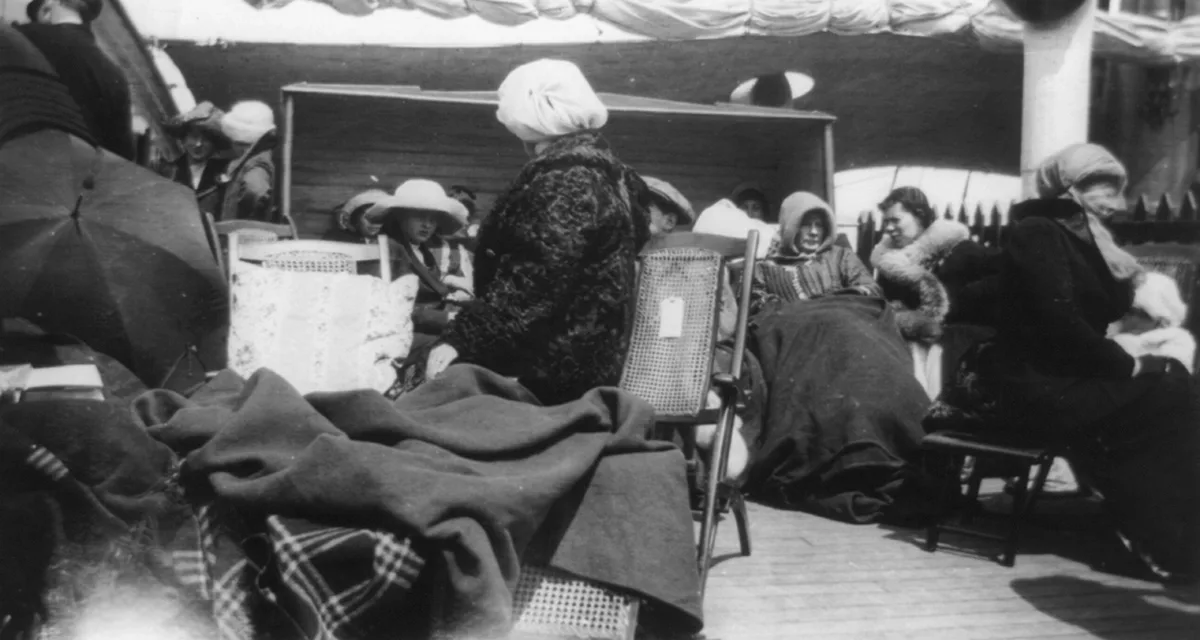

Two prominent Baslers had booked passage in first class as well: Alfons Simonius-Blumer and Max Staehelin. Alfons began his career as a colonel in the Swiss army, later becoming the respected president of the Schweizer Bankverein. He traveled to New York with Max, a finance lawyer and the director of the Schweizerische Treuhandgesellschaft. Throughout the voyage, they socialized with their friends, the Frölicher-Stehlis, in the Café Parisien and the First Class Smoking Room, discussing their respective business interests in the United States.

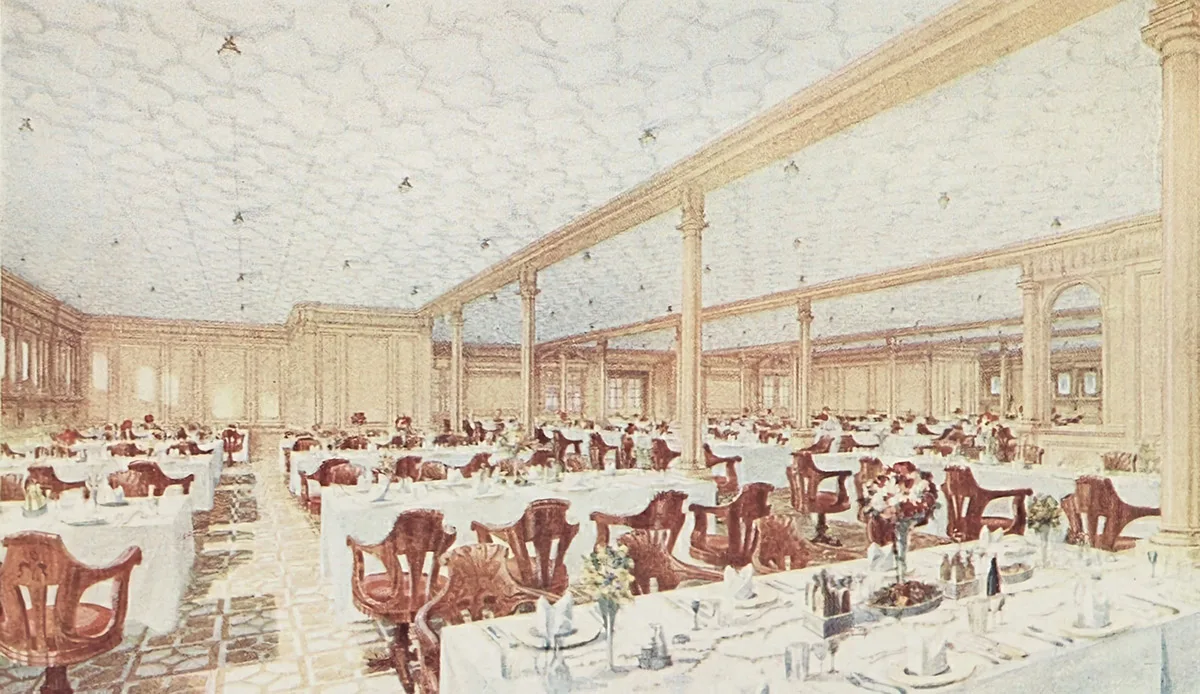

Josef Arnold and his wife Josefine Franchi from Altdorf (UR) traveled in third class as emigrants to the United States. Relatives in Wisconsin had paid for their tickets and while excited at the prospect of starting a new life in the American Midwest, they had to leave their infant son behind in Canton Uri. Their cousin, Aloisia Haas, also from Altdorf (UR), accompanied them, but her final destination was Chicago. She had long dreamt of life in what was then the second-largest city in the United States.

A night to remember

The Frölicher-Stehlis surveyed the situation, deciding to step into lifeboat no. 5, which was lowered around 12:45 AM. Not long thereafter, Alfons Simonius-Blumer and Max Staehelin entered lifeboat no. 3 right before 12:50 AM. Emma Sägesser got into lifeboat no. 9 around 1:30 AM with a distraught Ninette Aubart. As their lifeboat descended down into the Atlantic, Benjamin Guggenheim said his farewells to Emma in fluent German. Bertha Lehmann battled the growing crowds and made a lucky escape with other second class women in lifeboat no. 12, which was lowered around 1:30 AM. Marie-Marthe Jerwan had the good sense to dress warmly and pack a small bag of essential items before climbing into lifeboat no. 11 at 1:35 AM. By then, nearly half of the lifeboats were gone and no rescue ship was in sight.

His journey is finished. He has reached the place he set out for. But no ruddy cheeked (Swiss) lad will add his wealth of energy and labor to the industries of Beloit. Instead a little mound in the city cemetery marks the consummation of his life’s hopes and incidentally brings home to the people of Beloit, the great ocean tragedy that shocked the entire civilization of the present day and will go down in history as one of the great disasters of all time.

Historians are apt in stating that the sinking of the Titanic heralds the decline of the Belle Époque Era in Europe and the Edwardian Era in Britain. Ironically, it was another maritime disaster, which would signify the end of this epoch. It was that of the liner, which initially set the tone for sumptuousness at sea during the “long Edwardian summer”: the Lusitania.