Belle Époque in colour

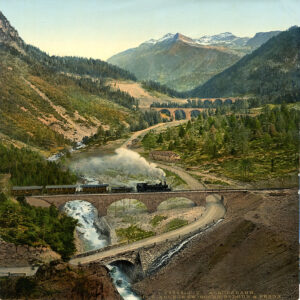

Colour pictures for everyone! That was the idea behind the photochrome process, which was devised in Zurich in the late 19th century – and quickly took over the world.

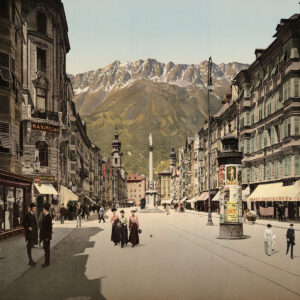

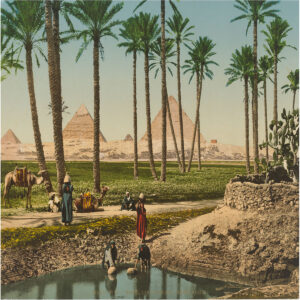

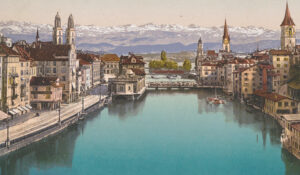

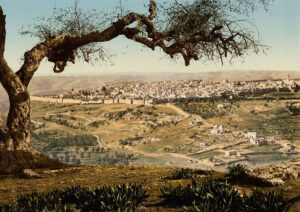

Focus on tourists

Touristy views of cities such as Zurich and Jerusalem were very popular during the Belle Époque. Zentralbibliothek Zürich

Black and white as a basis