The Carnation Revolution

In April 1974, one of Europe's oldest dictatorships collapsed in Portugal. In Switzerland, people were worried about the future of Portugal. Not least because of the fragile political balance in southern Europe.

On 25 April, the MFA took to the streets in Lisbon to take control of the city. It was quickly followed by civilians who demonstrated peacefully. The Estado Novo collapsed within a few hours. "It only took 15 hours for a regime of almost 50 years to collapse without a shot being fired," reported the Swiss ambassador in Lisbon, Jean-Louis Pahud.

In the crowd, a waitress of a restaurant decided to decorate the military's rifles with red carnations, unwittingly giving the revolution its name. Spínola, who briefly became president, released the political prisoners. Most of them were left-wing activists who had been imprisoned by António de Oliveira Salazar. They contributed to the MFA's transition from protest against the war to a genuine social revolution.

TV documentary about the Carnation Revolution in Portugal. YouTube

Powder keg Southern Europe

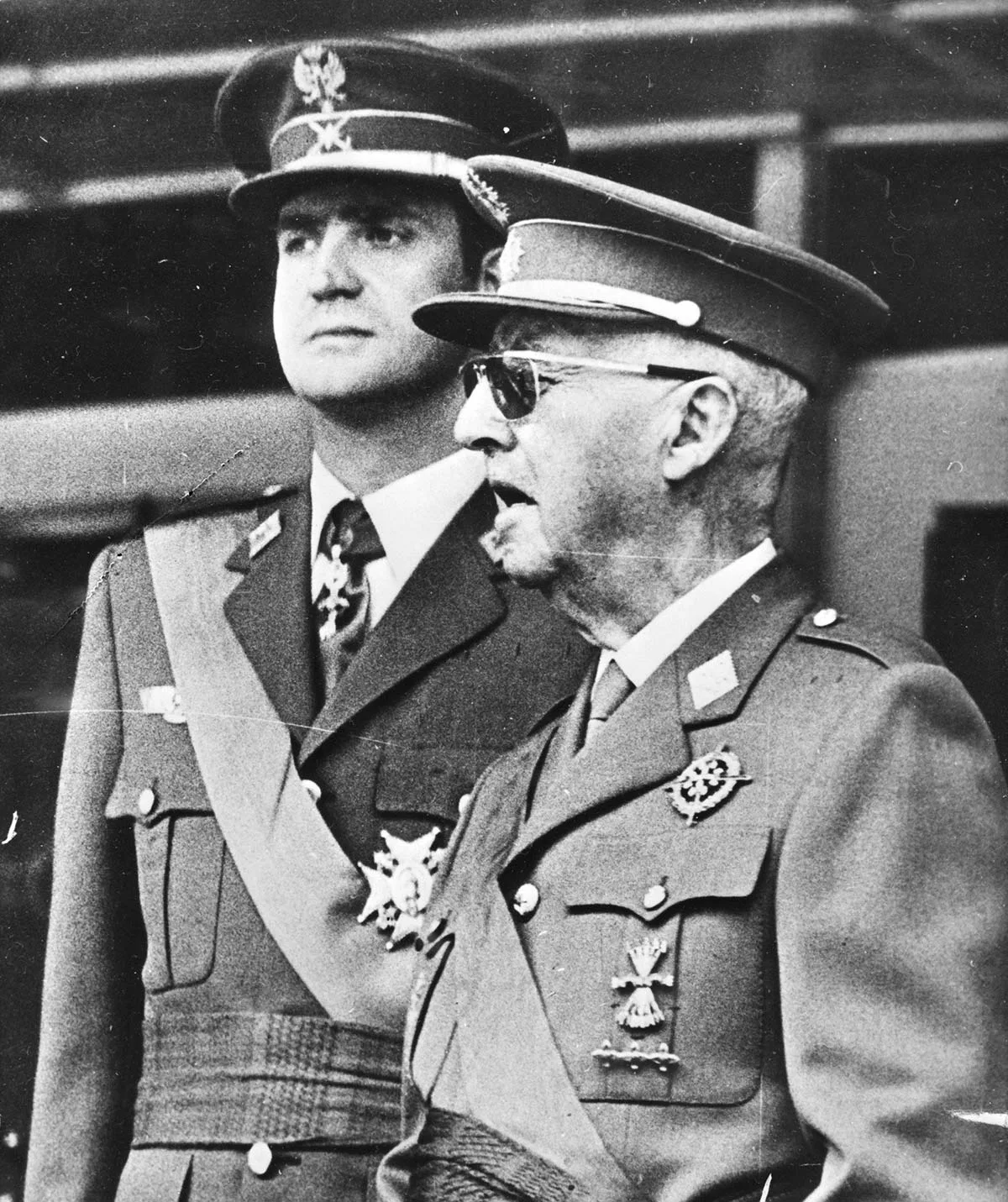

It is worth remembering that in 1974, Italy was the only one of these countries that was not led by an authoritarian government, although it was characterised by the severe tensions of the "Years of Lead". In Spain, the Franco regime was still in office despite Franco's worrying state of health and the resulting questions about the regime's continued existence. In Greece, the dictatorship of the colonels held power for a few more months. In the summer of 1974, the Cyprus crisis, the Turkish invasion of the north of the island and the barbaric repression of peaceful demonstrators by the Greek regime finally brought the junta to an end. All in all, there was a danger that the whole of southern Europe would become embroiled in civil war.

Fear of a left-wing regime

The Swiss ambassador in Lisbon reported on all – actual or alleged – misdeeds and machinations of left-wing organisations in a style that often seems surreal today and always portrayed them as being armed with the worst intentions. When General Spínola was forced out of office and fled to Switzerland, he was accused of wanting to buy weapons there. The Swiss ambassador in Lisbon initially announced that it was probably a coup by the communist press to discredit the army. But a few days later, the German newspaper Stern uncovered the matter: The general had actually made contact with a supposedly right-wing extremist armed group in order to buy weapons and ammunition.

Joint research

This text is the result of a collaboration between the Swiss National Museum (SNM) and the Swiss Diplomatic Documents Research Centre (Dodis). The 50th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution was the occasion for several publications and historical events that inspired this text. The documents accessible on Dodis are available online.