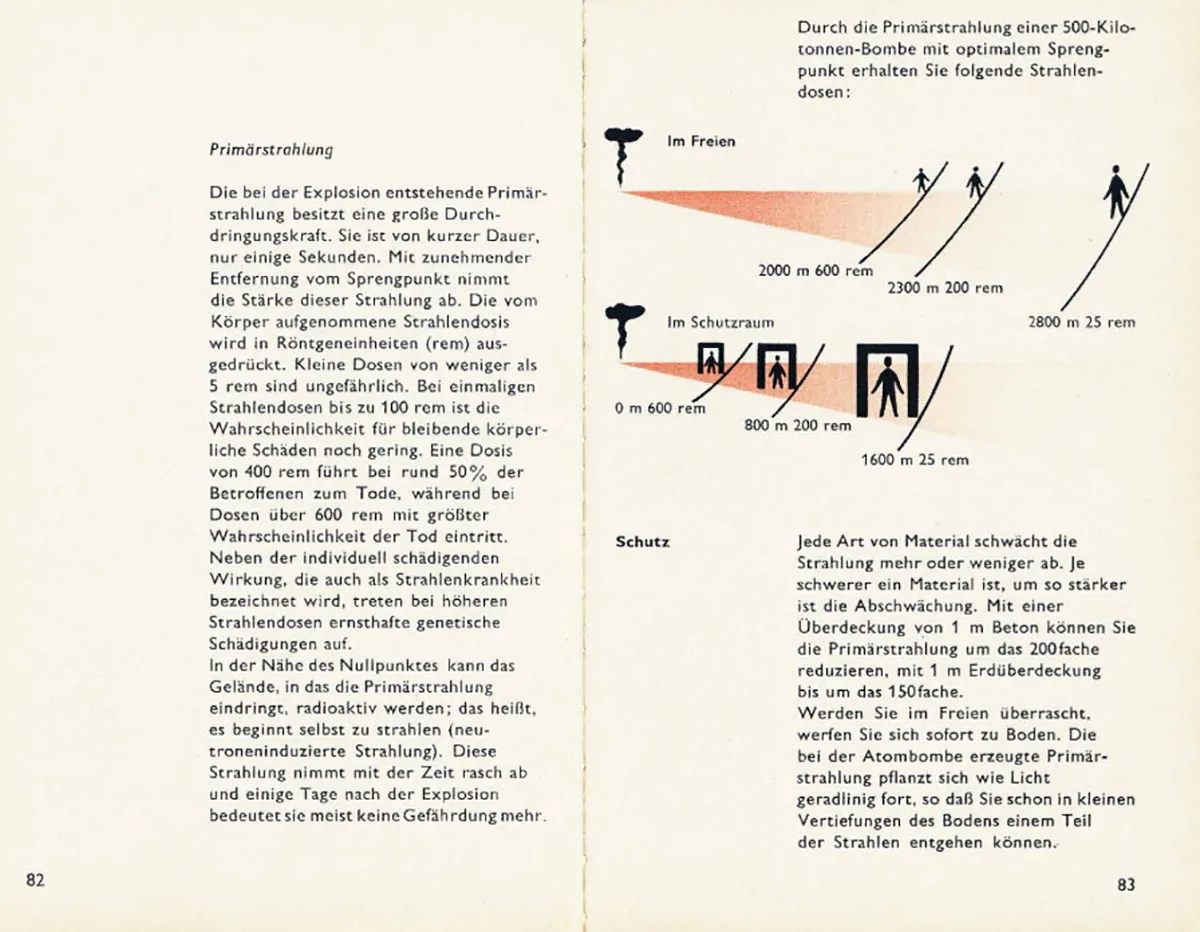

The civil defence of 1969: the war in people’s heads

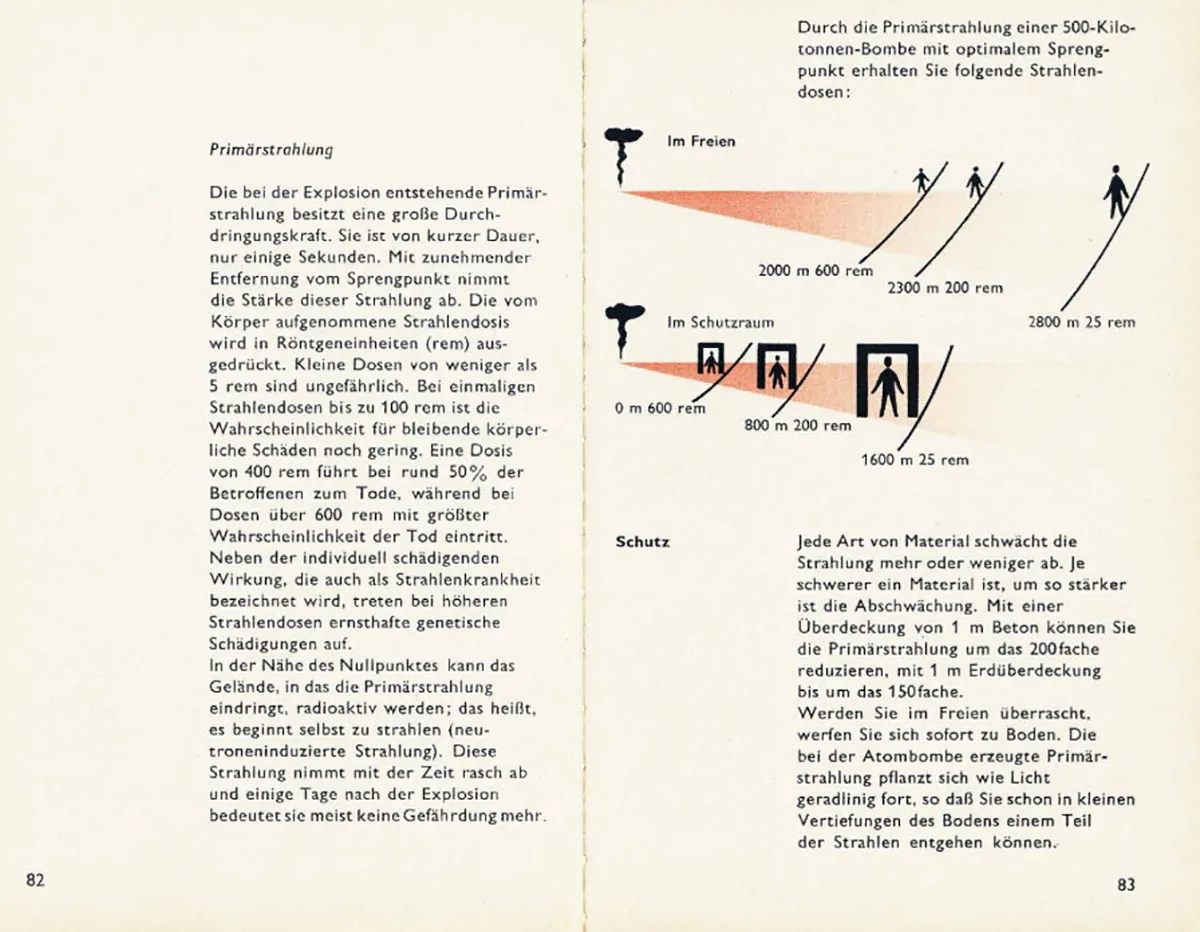

In 1969, the Federal Council had a little red booklet distributed to every household in Switzerland. It was the Zivilverteidigungsbuch, the Civil Defence book. The book caused red faces for years…

In 1969, the Federal Council had a little red booklet distributed to every household in Switzerland. It was the Zivilverteidigungsbuch, the Civil Defence book. The book caused red faces for years…