In search of riches in the rainforest

In the 1970s the Volkswagen group launched a major agricultural project led by a Swiss citizen that resulted in bonded labour and rainforest deforestation on a massive scale.

In 1970 “undeveloped” tropical zones were considered the world’s most promising reserves of natural resources and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations recommended their exploitation to satisfy booming market demands and fight human poverty on a global scale. In the developing world, fast-food consumption was growing steadily, and McDonald’s started to purchase its beef from the rainforests of Costa Rica. The world’s biggest tropical forest, the Amazon, was the new frontier of capitalism, and the Brazilian military dictatorship launched the building of the Transamazônica, a 5,000-kilometre-long highway that it was hoped would help economic actors to penetrate the as yet little exploited jungle. Generous fiscal incentives attracted hundreds of Brazilian and multinational companies in the region looking for speculative opportunities and juicy profits through the export of resources such as minerals, timber and especially meat. Swiss companies such as Nestlé were among the big names of this wave of land purchase, but there were other Swiss connections too.

It was the time of the “Green Revolution”, a massive transfer of Western expertise intended to modernise the agriculture of the developing world with the introduction of pesticides, genetically modified crops and mechanised monoculture. This process was often framed by its actors in humanitarian terms, as a first step for the “third world” to rise towards the wealth patterns of North America and Europe. Building on the international reputation of the Alpine pastures, Switzerland established itself in the foreground, training the world’s top agronomists. The Federal Polytechnic Institute of Zurich (ETH) was ranked among the world’s best schools in the sector.

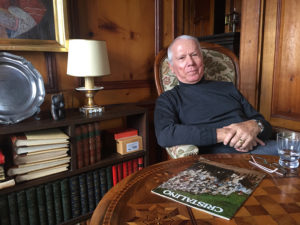

It was no surprise, in this context, that Friedrich Georg Brügger from Graubünden, who had graduated from the ETH in 1964, was chosen by the multinational company Volkswagen (VW) to supervise the Brazilian Government’s showcase Amazon development project: the Companhia Vale do Rio Cristalino, a 140,000-hectare “pioneer” cattle ranch launched in 1973 on the Southeastern rainforest frontier, financed and managed by VW to make the most of tropical resources with the help of up-to-date farming techniques. Forced by Brazilian law to reinvest part of its profits in Brazil, the German company saw Cristalino not only as a good investment, but also as an opportunity to strengthen its image as a bold and benevolent investor, by carrying out a social development project in the jungle. Brügger stood as a guarantee for Swiss quality and competence. He often joked: “The Germans call us Kuhschweizer (Swiss cow herders) anyway, so one of us had to come here and run the farm”. The pastures and herds were monitored by a computerised system based at VW’s Brazilian headquarters near São Paulo, and the programme was followed by researchers from ETH Zurich, from Hanover’s veterinary school, and from the University of Georgia in the United States. These scientists carried out research to produce the cattle breed best adapted to resist tropical diseases while having similar physical characteristics to cows bred in temperate climates, in order to meet the demands of Western consumers and have a chance of breaking into the export market. The ultimate objective was to create “the ox of the future”: a breed that “combines the virtues of the hardy zebu with the productivity of European breeds”, according to an official brochure from 1983.

Location of the Companhia Vale do Rio Cristalino cattle ranch in Brazil.

Map: Wikimedia

Approach towards the Cristalino farm, photographed in 2017.

Photo: Stefanie Dodt

“The ox of the future” did not have time to emerge out of the Cristalino project, which was brought to an end by the Brazilian monster inflation crisis of the mid-1980s. The high initial technical investment made it difficult for the cattle ranch to sell beef at an affordable price. In the end, it contradicted the assertion of VW public relations that Cristalino was an expression of the wealthy countries’ duty to help feed the hungry “third world” thanks to the benevolent action of multinational companies. Above all, the project deeply wounded the rainforest and its population. Cristalino led to slash-and-burn activities of a previously unseen magnitude and involved criminal local subcontractors who exploited forced laborers from the poorest rural classes of the Amazon to do the clearing and fencing for the ranch. Historical testimonies from these workers point to a system of debt bondage, often also described as “peonage”: a system under which an individual is indebted to an employer and forced, under pain of criminal punishment, to continue working for that employer.

Brügger reacted in the most disastrous way to the international scandals provoked by these abuses. In 1977, a British journalist who visited Cristalino witnessed one of his sudden mood swings when the subject of environmental protection was mentioned. As she timidly brought up the question of ecological viability, he banged on the table and said: “don’t you speak to me about ecology!” Environmentalism, he said, was “a new-fangled profession, recently invented by out-of-work intellectuals who have nothing new to say.” When he wanted to impress guests coming to the ranch, he offered them objects made of precious, endangered timber species whose extraction and trade was forbidden by law. Even more shocking were his reactions to the accusation of forced labour raised against Cristalino. According to him, Amazonian workers were “nomads,” naturally lazy and reluctant to take on regular employment or work efficiently. He did not want to know about “debt slavery”, which he saw as a pseudo-humanitarian concept invented to justify the workers’ laziness. Instead of earning money, Brügger said, Amazonian workers augmented their debts “because they live beyond their means” and “eat mountains of rice instead of working”, which in the end explained and justified their situation as indentured laborers. Brügger’s despising discourse towards the victims of rural inequalities unveiled the underlying logic of the “VW ranch”: a sophisticated way of reproducing patterns of colonial exploitation of the global south to enrich the global north.

Before the 1960s, most inhabitants of the Amazon had never seen a cow. The only existing cattle species of the region were the water buffaloes of the Marajó Island in the Amazon delta. Today, Brazil accounts for 20% of the world’s beef exports and cattle ranching is the largest driver of deforestation of the Amazon. International organisations no longer recommend developing tropical cattle ranching; instead they relentlessly warn against it as a major threat to the world climate. Like many scientific schools today, the ETH now supports sustainable farming approaches and its research programmes on global nutrition focus on low environmental impact and fair trade. Yet, in Brazil, the local and international agroindustry no longer seeks humanitarian pretexts to accumulate wealth at the expense of biodiversity. Beef and soil investors lobby openly for the end of environmental protection measures and of Brazilian state programmes against forced labour. Cristalino is where it all began, under the guidance of an ETH-trained agronomist who liked to laugh about being called a Kuhschweizer.

Entrance to the farm, 2017.

Photo: Stefanie Dodt

A VW beetle stands ready during the rounding up of the cattle.

TV Tip

Report in the ARD Weltspiegel on daserste.de (in German)

Friedrich Georg Brügger during the interview with the ARD.