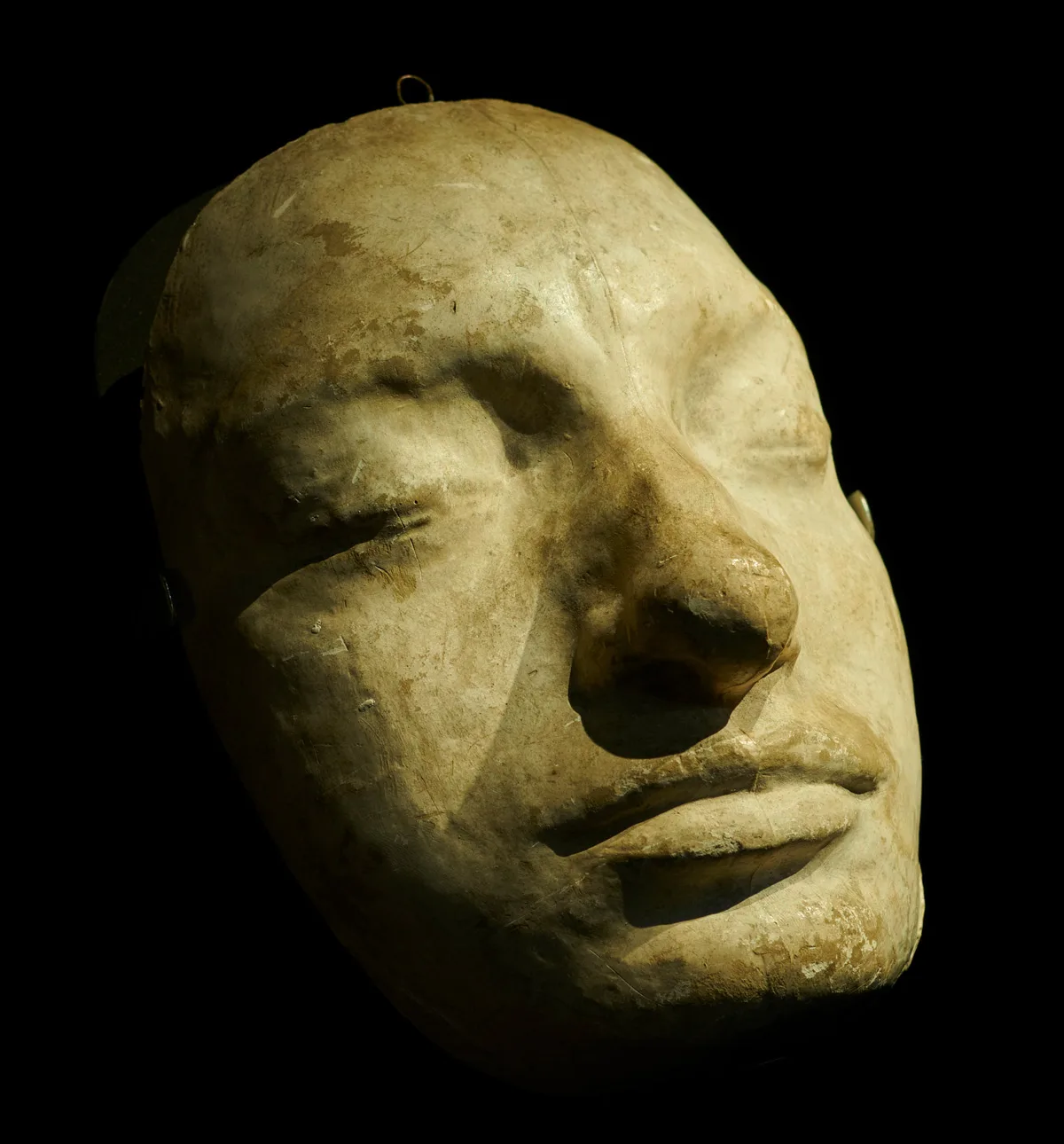

The Lady Behind the Mask: Joan of France

The exquisite death mask of Joan of France (1464-1505) mirrors the grace, courage, and moral convictions of a long-suffering disabled woman who was briefly queen of France and later canonized as a saint.

Marriage in the Name of Politics

I have resolved to make the marriage of my little daughter Joan and the little Duke of Orléans because it seems to me that the children they will have together will cost nothing to feed. I warn you that I hope to make this marriage and those who oppose it will not be sure of their lives in my realm.

Unsteady Times

I beg you to bear the case of my husband in mind and to write about him to our brother […].

Ascending to the Throne

Had I thought that there was no real marriage between the king and me, I would beg him to leave me to live in perpetual chastity because that is what I desire the most […] to live spiritually with the Eternal King and be His spouse.

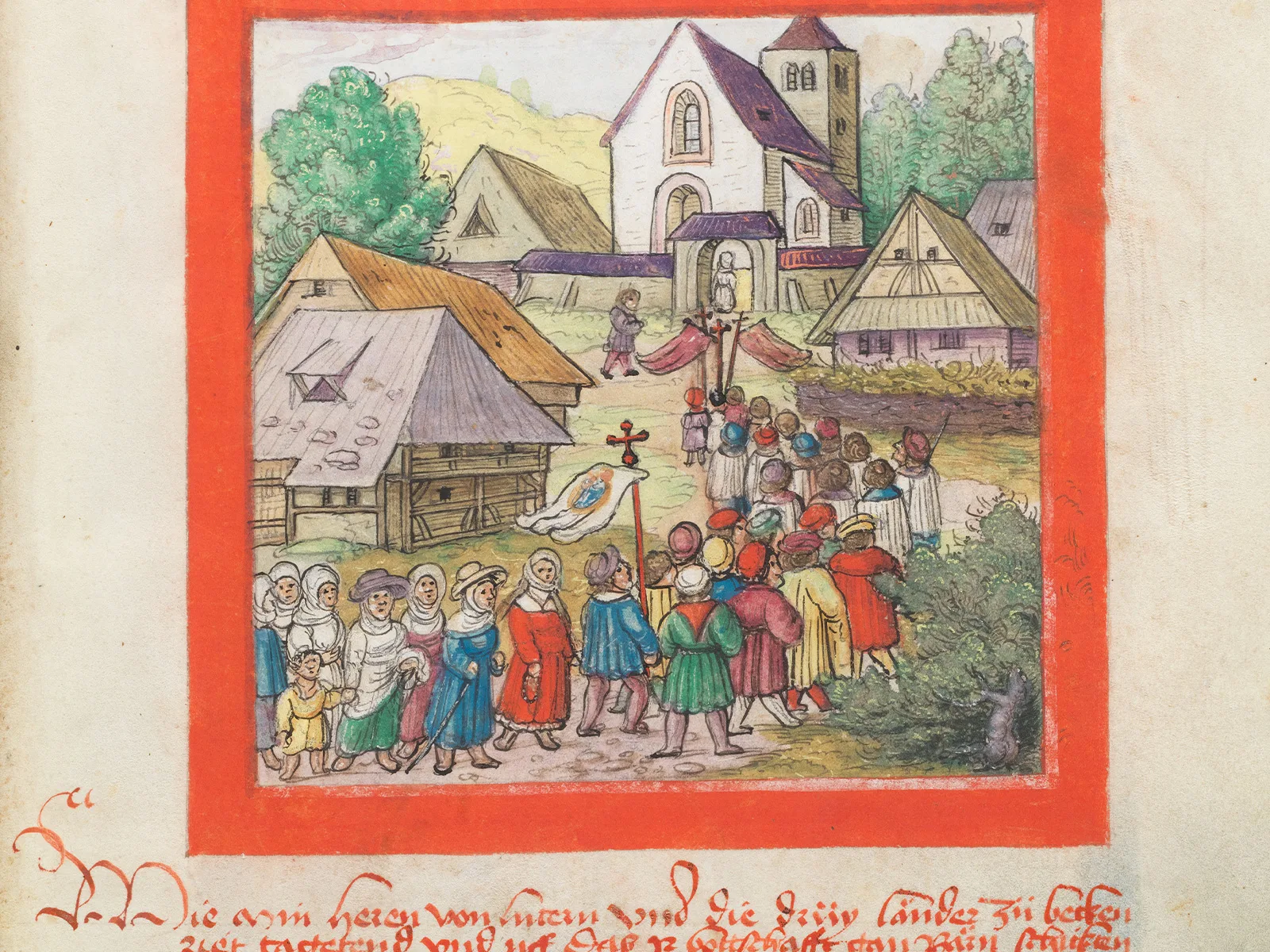

From Queen to Saint: Joan’s Legacy