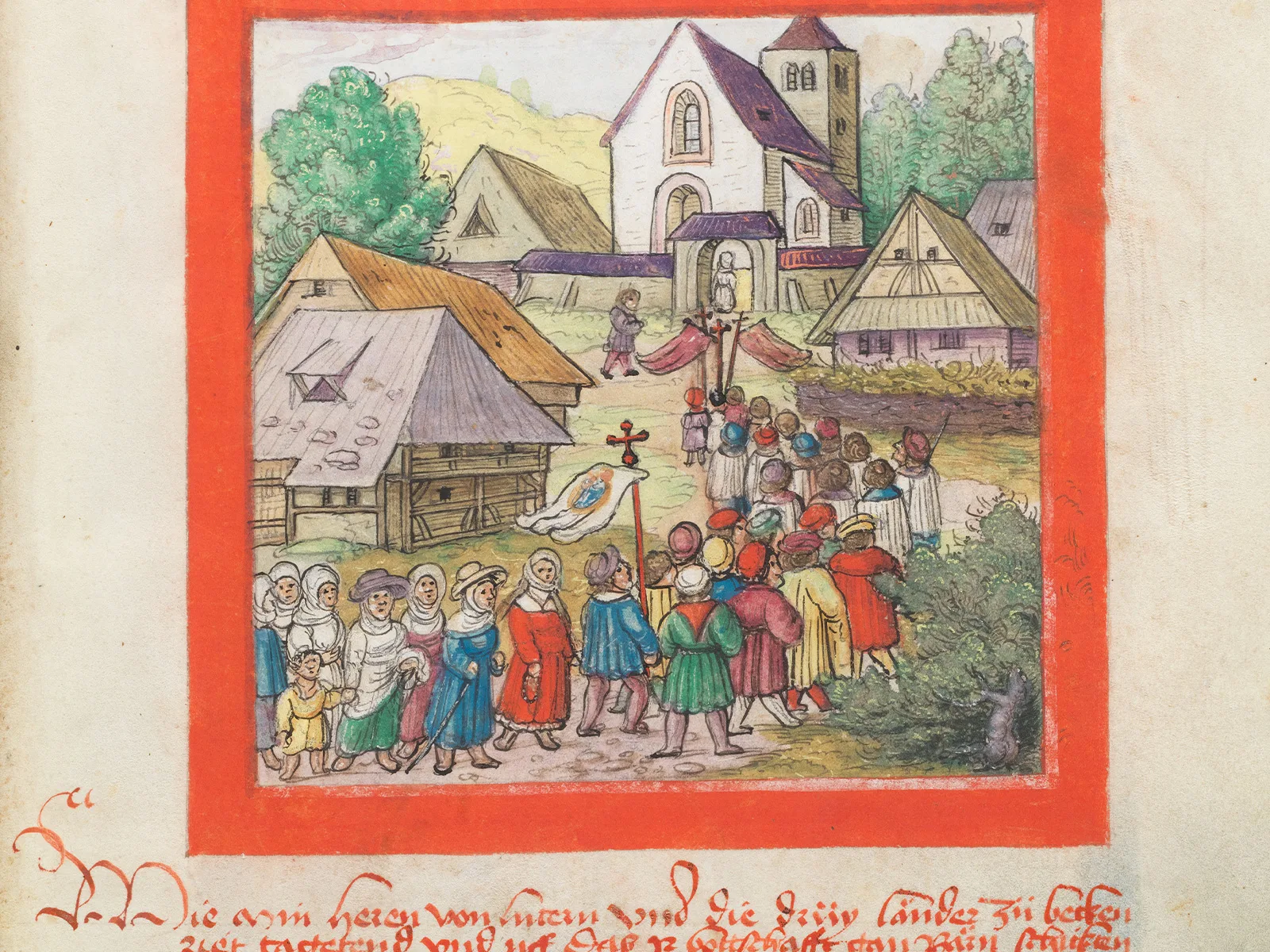

Risen from the dead

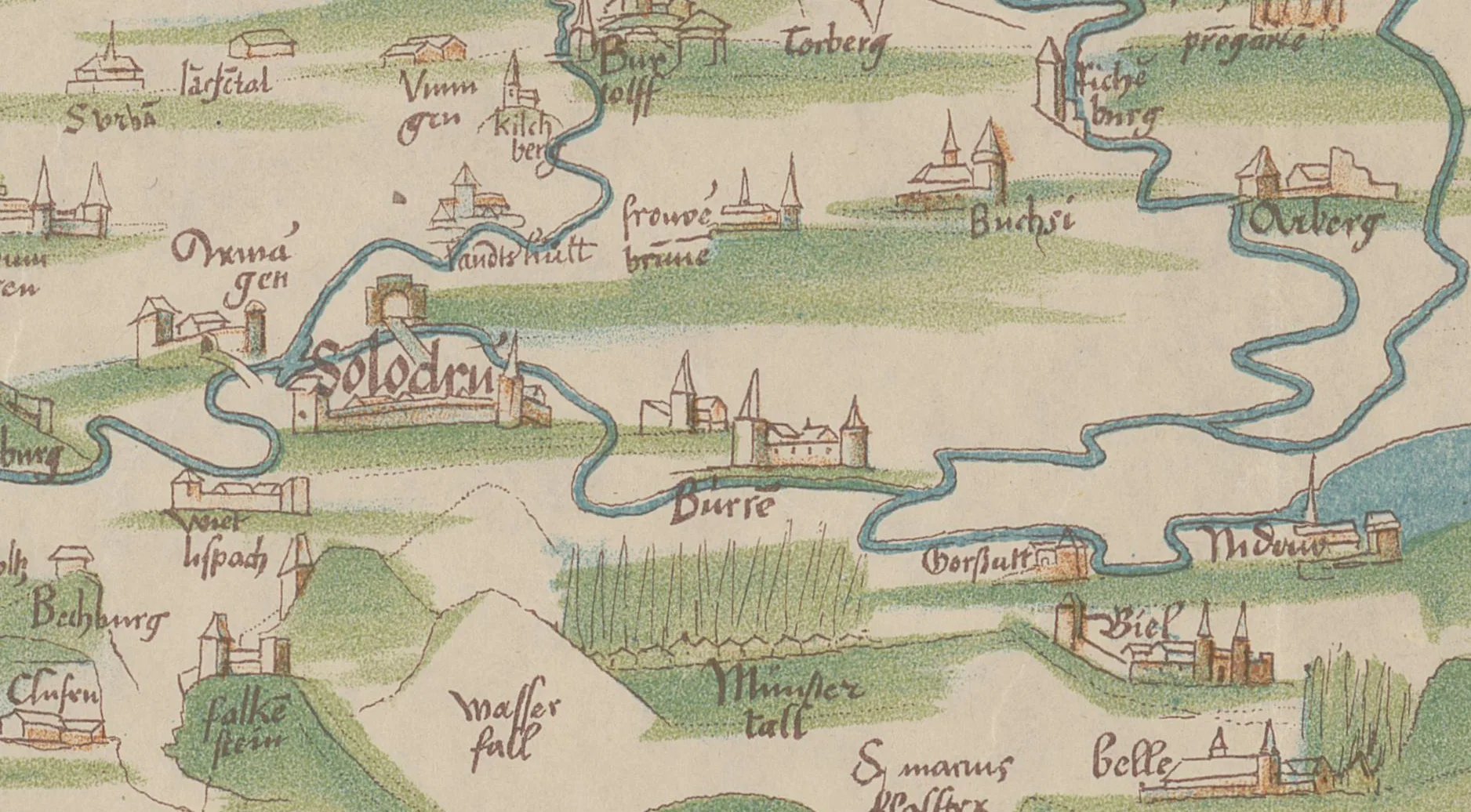

At the Marian shrine of Oberbüren (Canton of Bern), the medieval Catholic Church offered some very special services: children who were stillborn or had died at birth were briefly brought back to life so that they could be baptised and then properly buried.