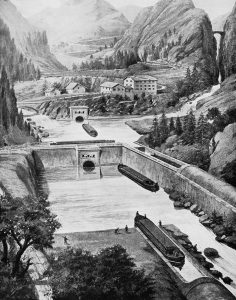

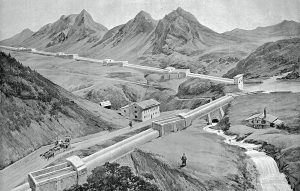

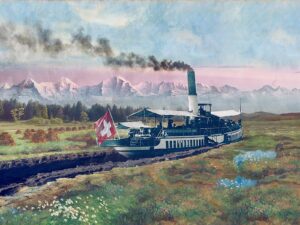

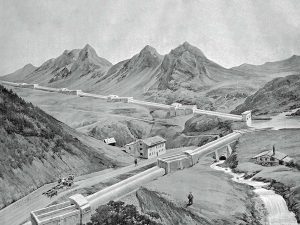

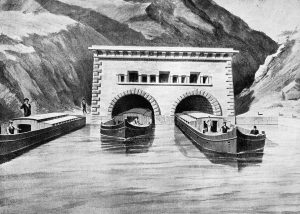

The dream of an alpine waterway

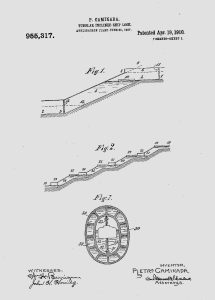

Pietro Caminada had a simple idea to turn the inconceivable into reality: huge cargo ships crossing the Alps without using self-propulsion. The stroke of genius by the engineer with Graubünden roots was a viable project – at least he thought so.

The pioneer of Brazil

Communicating lock chambers

An audience with the king

“A technical fantasy”