Victims of Labour – a memorial that broke the mould

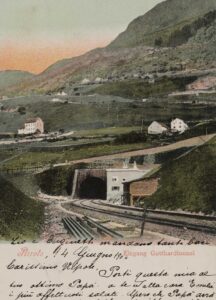

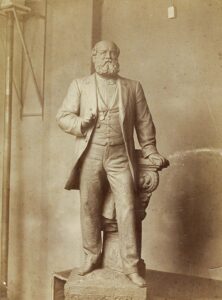

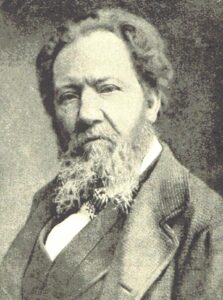

Artists were among the many to draw inspiration from the opening of the Gotthard railway tunnel 140 years ago. Prominent Ticino sculptor Vincenzo Vela created a contemporaneous memorial to those lost during its construction, entitled Victims of Labour. This key work was not particularly well received at the time, however.

A prophet in his own land