Green gold from Dutch India

In the late 19th century, landlocked Switzerland was looking for ways to harness the immeasurable diversity of tropical botany. It found what it was looking for in Buitenzorg on the island of Java.

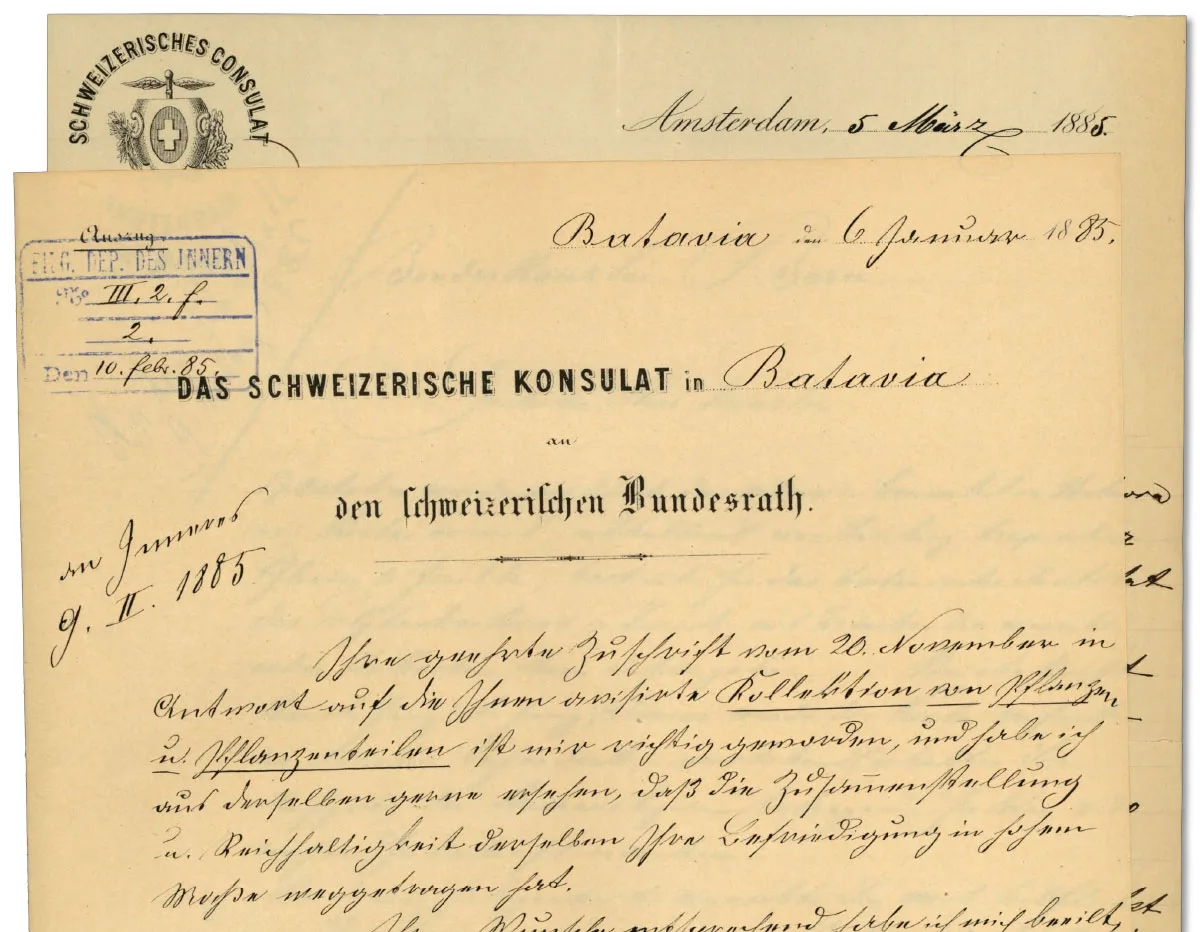

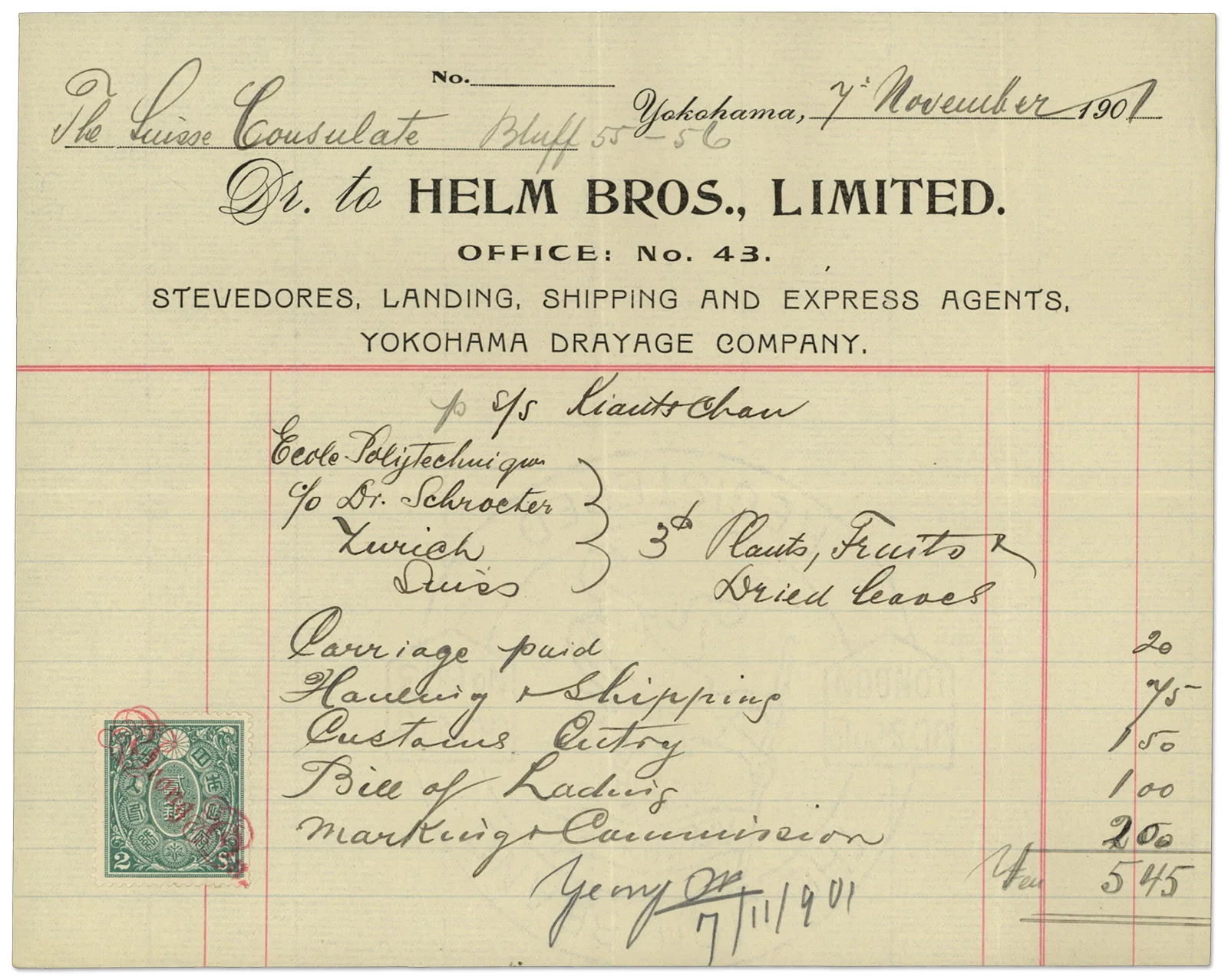

The botanists and pharmacists at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School (which became ETH in 1911) tasked with amassing scientific collections had been worried for some time that, as a landlocked country, Switzerland would have only very limited access to tropical fruit, seeds and ‘drugs for medicinal purposes’. In addition, the laboratories of food manufacturers were pushing for ‘exotic’ natural products with which they could develop new technologies and products. “The focus of these requests was applied knowledge for industry,” wrote historian Andreas Zangger in his definitive work Koloniale Schweiz (‘Colonial Switzerland’). Unlike Britain with its Empire and the Netherlands with its Maritime Empire, which could procure raw materials and goods from their colonies at will, Switzerland was long reliant on the patriotic goodwill of its nationals overseas or on shady merchants to meet its requirements, while generally avoiding costs.

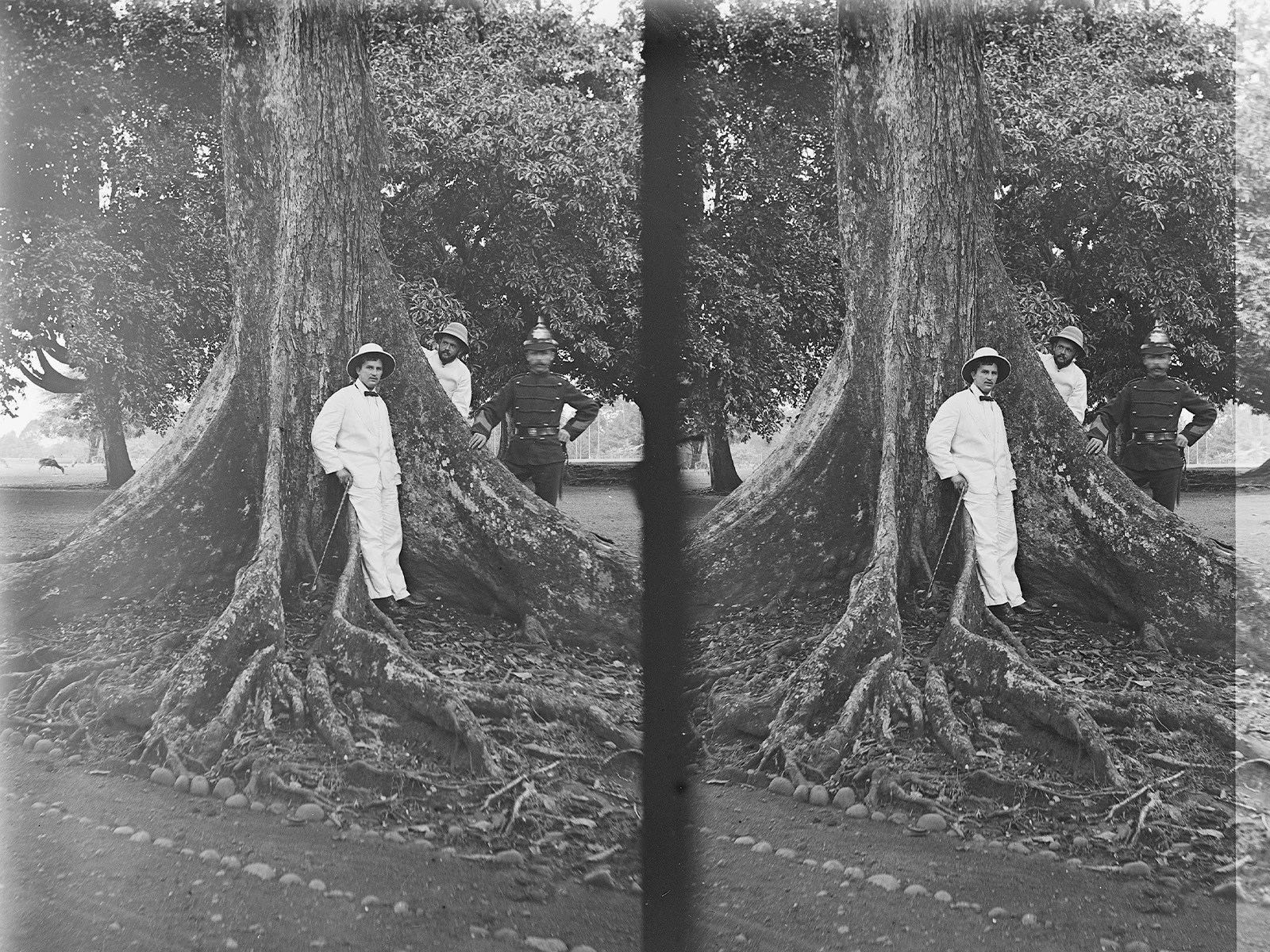

The botanic garden, located in what is now the Indonesian province of West Java, had been established in 1817 at the official residence of the Dutch governor. Over the subsequent decades, it went on to become one of the world’s most influential and advanced centres of botanical research and teaching. At the heart of Buitenzorg’s success was applied botany, and it earned a reputation as a ‘central institute for botany’. Scientists from all over the world worked there in what were known as ‘visitors’ labs’, and international agronomy companies set up testing facilities for sugar, coffee, tobacco and rubber (US Rubber Plantations) on the site. Genevan botanist Bénédict Hochreutiner reported in the Journal de Genève in 1904: “It is not a garden, a study facility or an institute; it is a faculty of science geared towards botany.” The Dutchman Treub, whose mother was Swiss, immediately understood what the request for assistance from the Federal Council was all about. With his cleverly-chosen selection, he paved the way for the Swiss science community to access the diversity and biodiversity of the tropical plant world, for which the Federal Council expressed its “great appreciation and warmest thanks” in November 1884.

Many later took up professorships at Swiss universities, while others dedicated themselves to ethnology, or were seconded by Switzerland to international organisations.

With its 15,000 tree and plant species, the 80-hectare botanic garden in Bogor (Kebun Raya Bogor) is still an important centre of botanical research.