Ossola’s partisans in Swiss internment camps

In 1944, many partisans from the Ossola region fled to Switzerland, where they were detained in remote internment camps.

After sweeping to victory, the fascists claimed that some 50,000 people had fled to Switzerland. Given that the entire population of the region at that time numbered 80,000, this was clearly a gross overexaggeration intended to make their triumph appear more impressive than it actually was. Current estimates put the figure at no more than 10,000 refugees, including roughly 3,000 partisans.

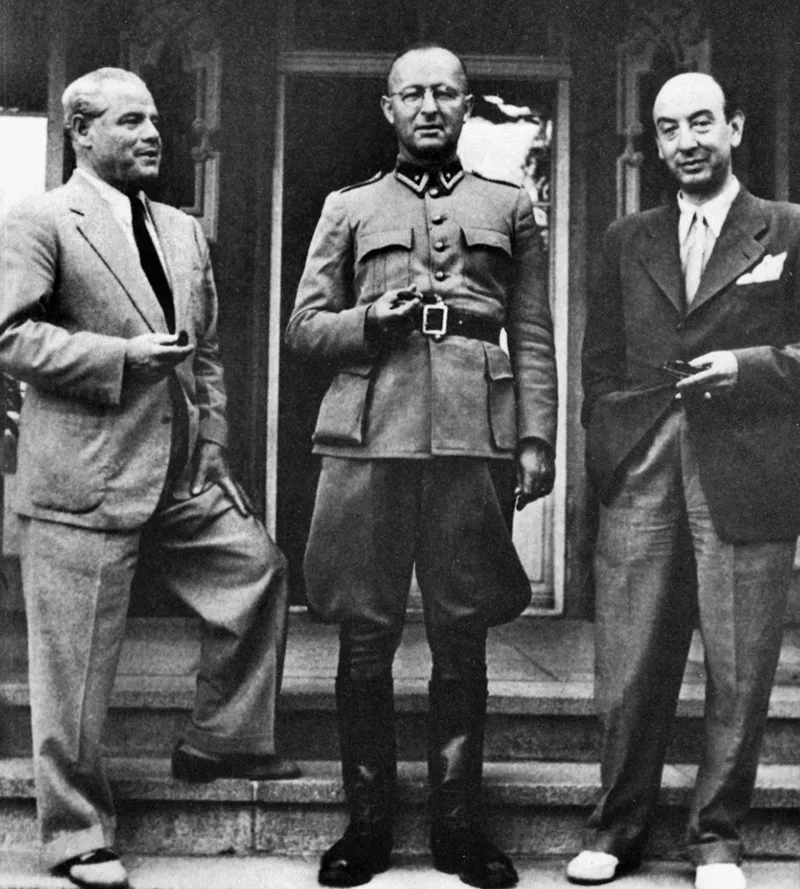

The local and cantonal politicians were almost certainly swayed into taking decisions that otherwise lay outside their remit by the fact that the people living close to the border in Valais and Ticino were affected most by what was happening and knew all too well what the German occupation and fascist presence south of the border really meant. For their part, the churches, the Red Cross and various other organisations swung into action to help the Partisan Republic, for example. But if the exhausted partisans were expecting to find a warm welcome awaiting them in Switzerland, they would be disappointed.

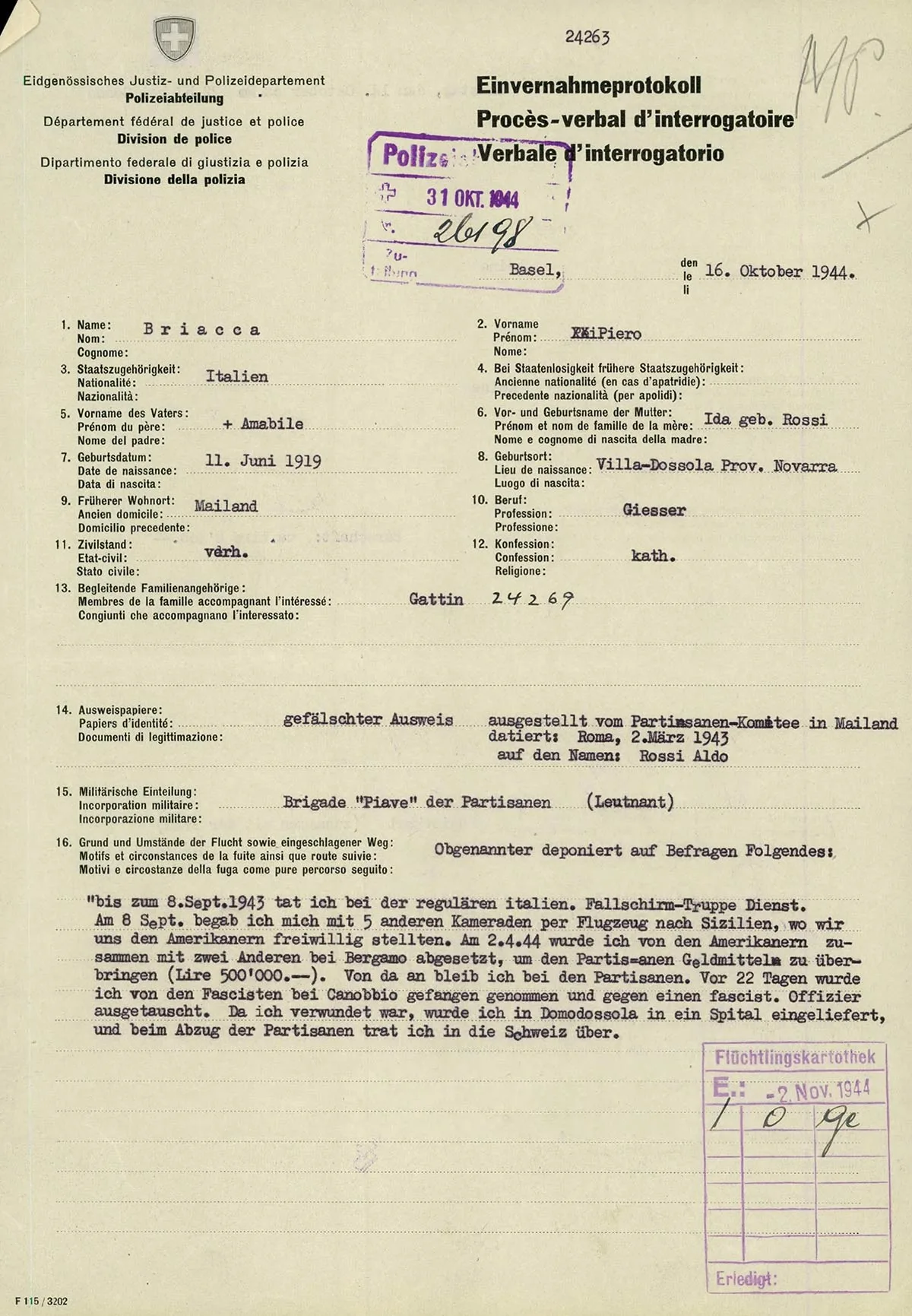

Internment in Switzerland

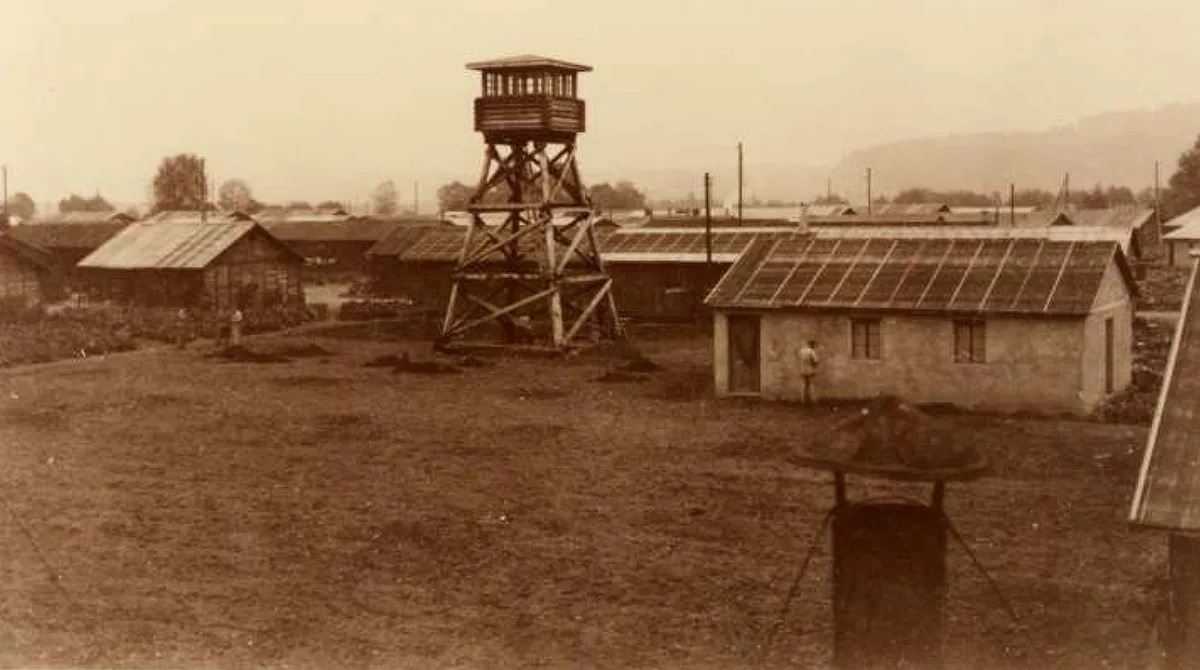

Following interrogation, each partisan would be transferred to one of the many labour camps in Switzerland. If they had entered the country via Ticino or Valais they would generally be sent to the other side of the Alps to put as much distance as possible between them and the border.

Consequently, almost all of Ossola’s partisans ended up in internment camps in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, many of them in canton Bern: outside Thun, in Mürren, Finsterhennen, Gurnigel, Büren an der Aare or Langenthal. Some were sent to canton Zurich (Wetzikon, Girenbad and Wald bei Hinwil, Adliswil, Nänikon) or to canton Aargau (Bremgarten). The camps were usually set up in out-of-the-way locations to prevent the inmates from coming into contact with the civilian population.

Return to Italy

For those who stayed on, opportunities for work remained very limited. The military, which was in charge of assigning labour, was extremely slow in dealing with job offers from Swiss companies. There would have been enough work to go round, primarily in agriculture and forestry, as most Swiss men were away on active service at the time. However, applications and requests for work were not processed expeditiously, and an analysis of hundreds of files on the internees creates the impression that the bureaucratic machinery was exceptionally slow, especially towards the end of the war. However, this is a stroke of luck for today’s historical researchers, as it allows them to reconstruct in some detail where individual refugees were detained.