The Ossola Republic

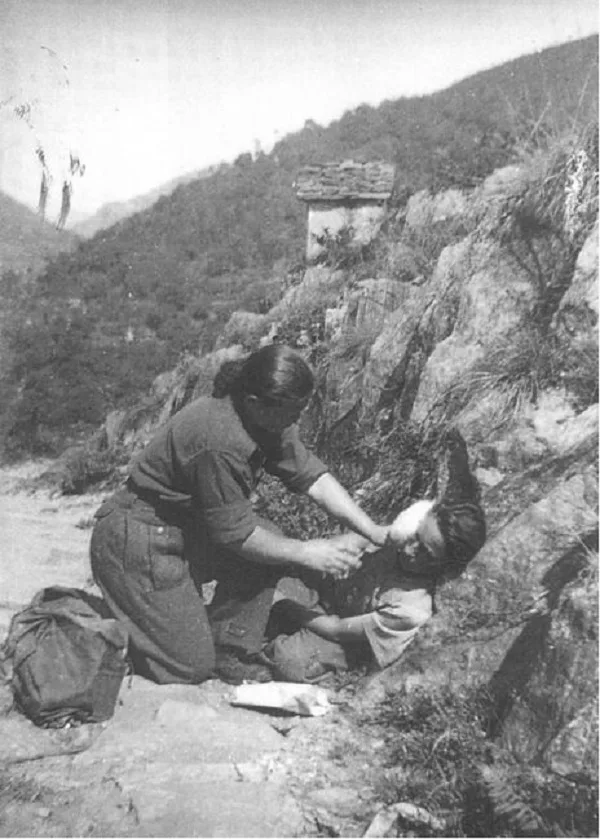

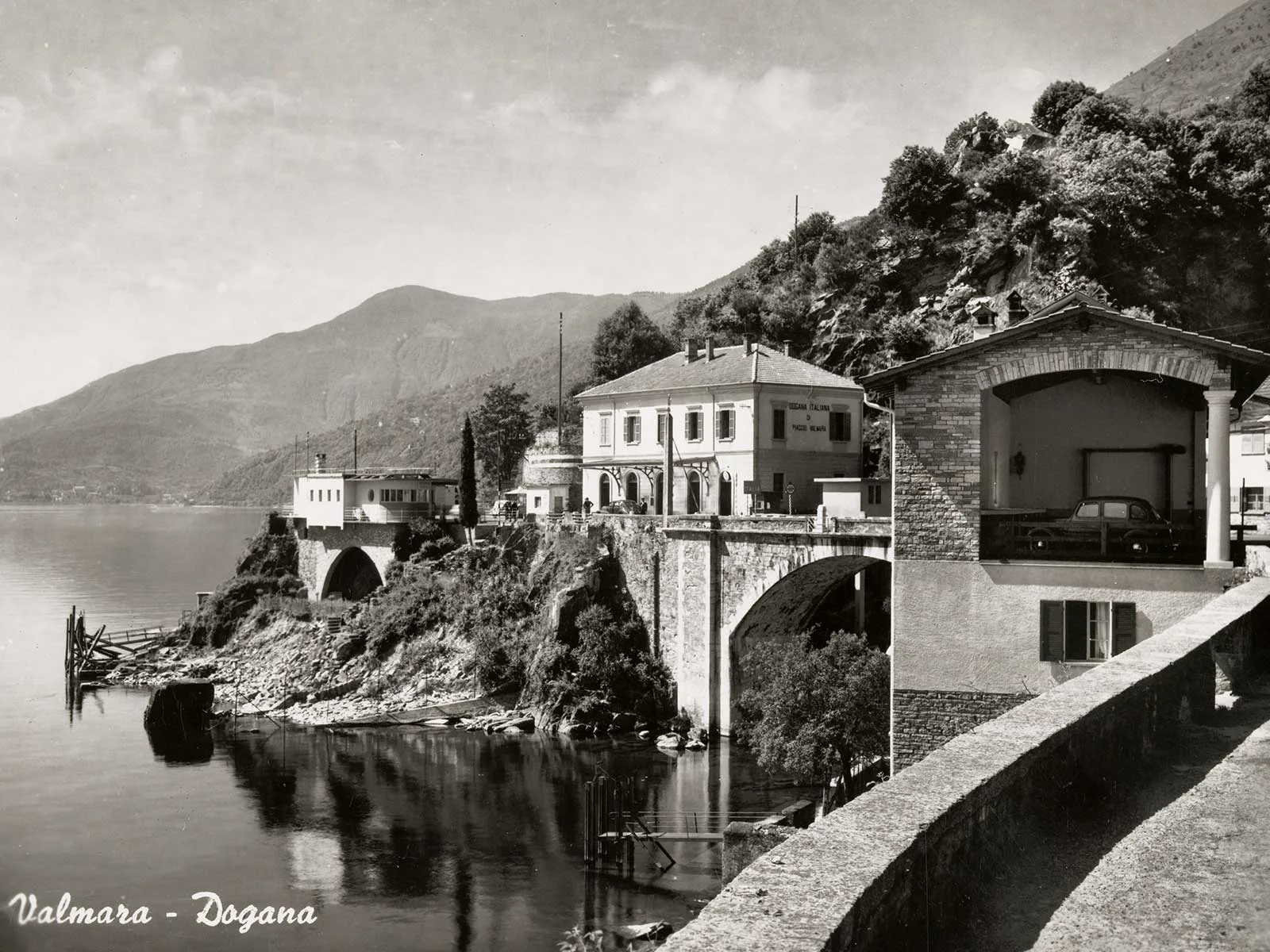

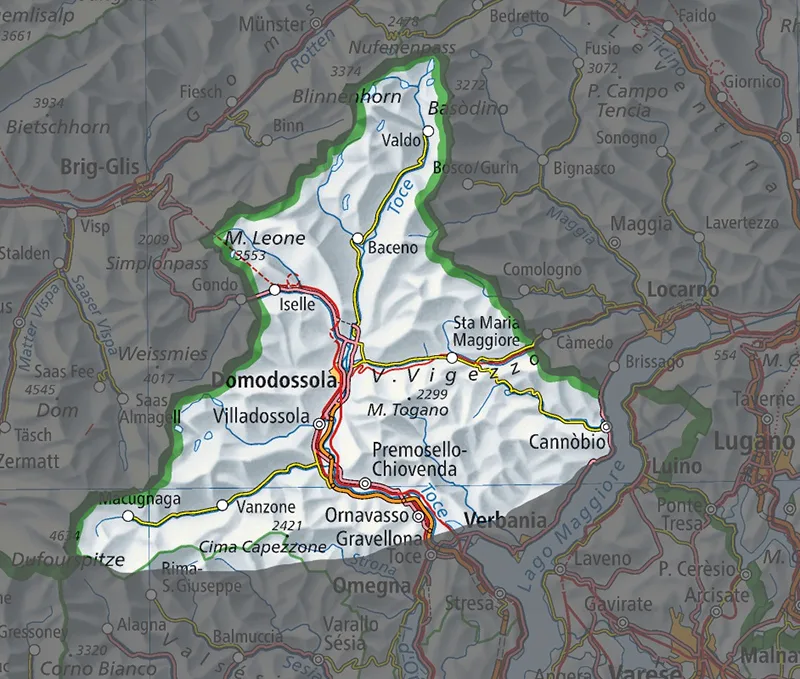

In autumn 1944, partisan groups liberated a sizeable territory around Domodossola from the Nazis and founded their own republic. But the resistance fighters were at odds with one another and after just over a month the dream of an independent state came to an end. The story of a tragedy on the border with Switzerland.

The internal power struggle among the partisans

Communists go it alone

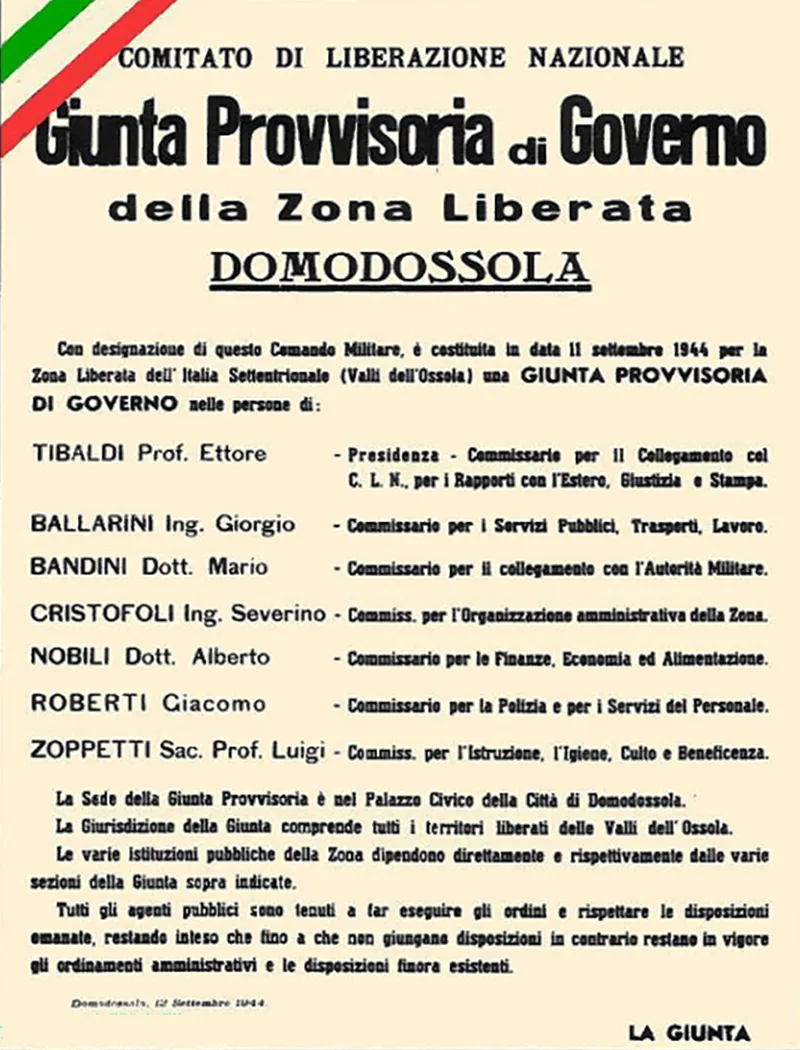

A republic!

The end of a dream