The Saracen Raids of Early Medieval Switzerland

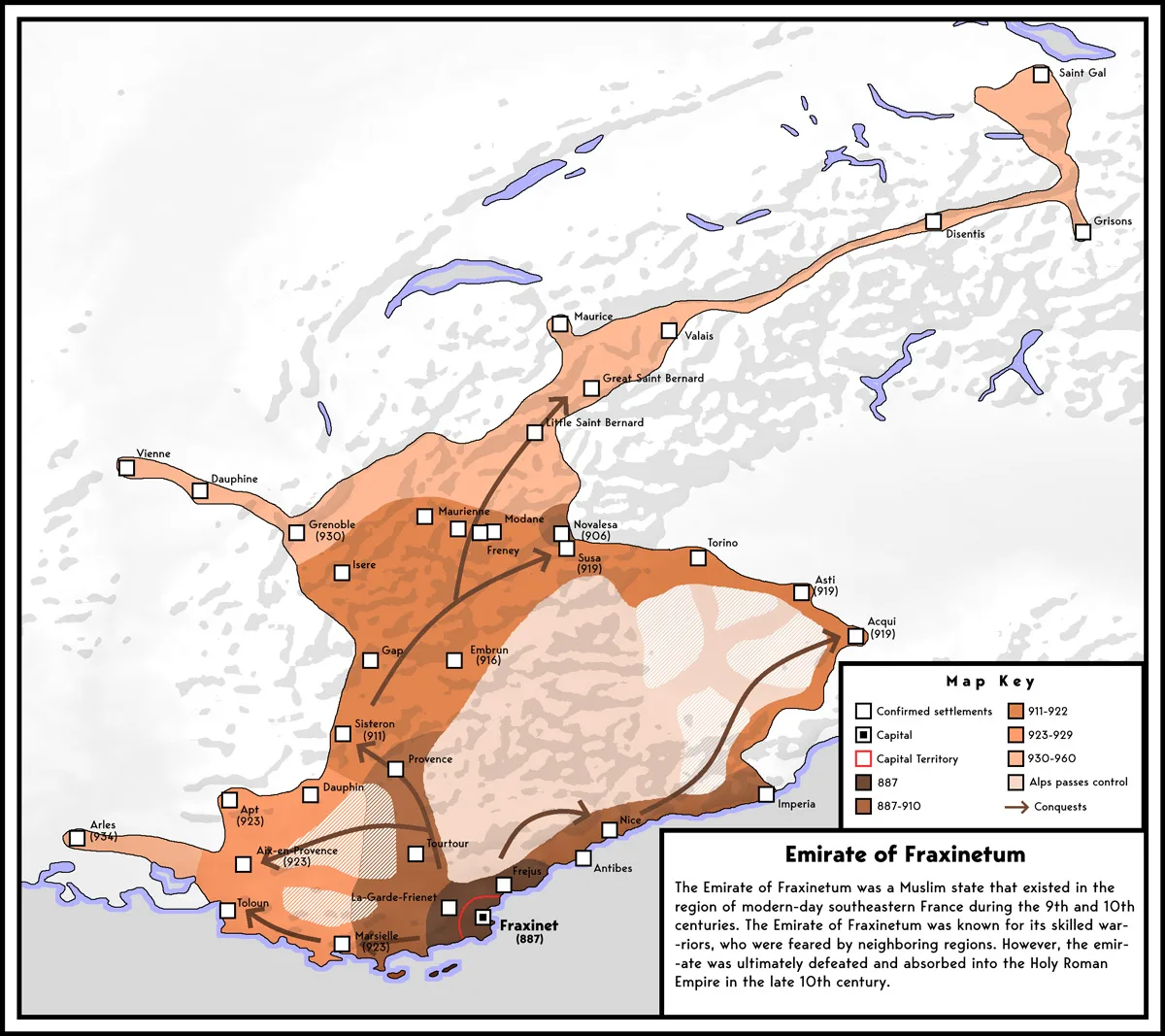

During the tenth century, barbarian raids affected large parts of what is now Switzerland. Seizing control of the western alpine passes, Saracens from the Emirate of Fraxinetum dominated the crucial arteries of trade and pilgrimage between France, Italy, and Switzerland for nearly a century. Much of Switzerland fell under their sway.

The Establishment and Growth of Fraxinetum

The term “Saracen”

The origins and motivations of those who populated and established Fraxinetum remain a subject of scholastic conjecture. The conquest of La Garde-Freinet may simply have been the work of shrewd pirates with knowledge of coastal and mountain fortifications. It is probable that many were of Berber origin and that some came from the Balearic Isles of Spain. Christian renegades and opportunists joined their ranks in all probability too. Aside from quick plunder, others were perhaps motivated by religious merit and the pursuit of extending the borders of Dar-al-Islam through jihad.

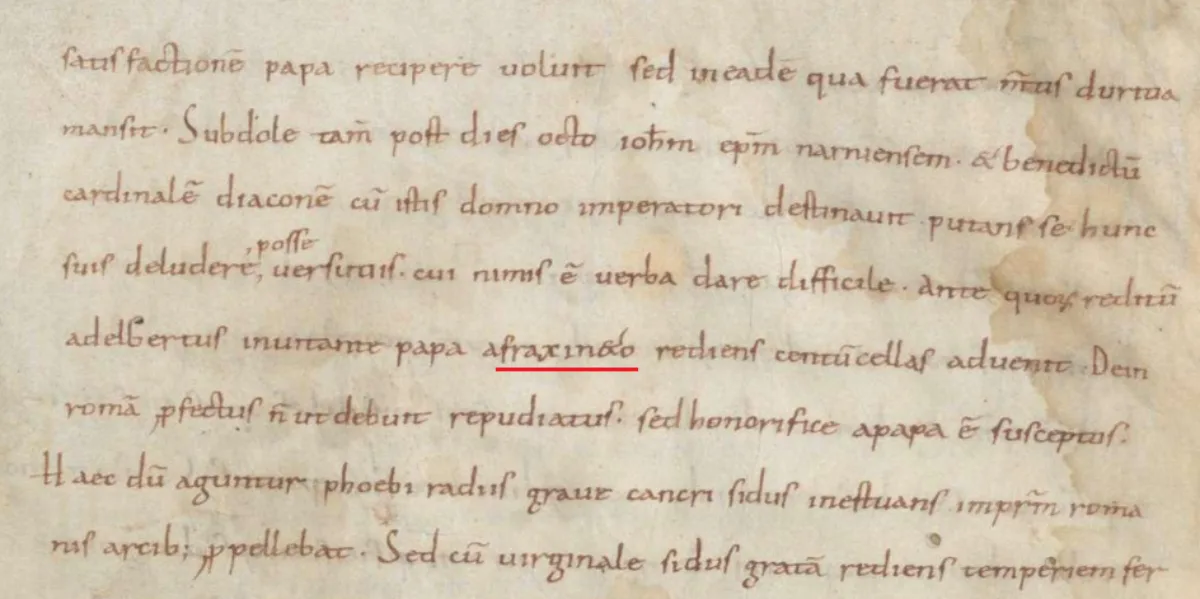

Sources from the Islamic world are rather limited in scope on the topic of Fraxinetum. The Arab geographer Ibn Hawqal (d. 978) may have made direct references to Fraxinetum in his Surat al-ard, but the Umayyad historian Ibn Hayyan al-Qurtubi (d. 1076) does include a brief mention of it in his chronicle, Muqtabis. Many more references about Fraxinetum are found in contemporaneous Christian chronicles and records. The famed chronicler and bishop Liudprand of Cremona (920-972) mentioned Fraxinetum in his Antapodosis and Liber de rebus gestis Ottonis. He opined that the Saracens of Fraxinetum owed their allegiance to the Umayyad Emirate of Córdoba.

The almighty God wished to punish the Christians through the ferocity of the heathen, a barbarian people invaded the kingdom of Provence and spread everywhere. They became very powerful and having obtained the most fortified place for their living, destroyed everything, laid waste very many churches and monasteries…

Fraxinetum’s Raids into Switzerland

It is unclear to historians the exact routes the Saracens pursued in their raids and invasions of alpine Switzerland, but it is verified that they plundered western Valais and sacked the Abbey of Saint-Maurice d'Agaune in 939. The Frankish chronicler Flodoard of Reims (c. 893-966) confirms that attack and records further that the Saracens targeted groups of pilgrims on the way to Rome in 940. Around the same time, the Saracens destroyed the church of St. Pierre in Bourg-Saint-Pierre, which was only rebuilt in 1010. Surviving diplomatic letters state that Chur and its cathedral were ravaged in a raid around 936, along with a church in Schams.

The monk and chronicler Ekkehard IV (c. 980-c.1056) attests to the presence of Saracen marauders in eastern Switzerland in his Casus sancti Galli, but he additionally delineates that the monks of St. Gallen put up a fierce resistance when attacked in 939. In contrast, the monks at the Benedictine Abbey of St. Disentis fled to the vicinity of Zürich, when the Saracens assailed their monastery around 941.

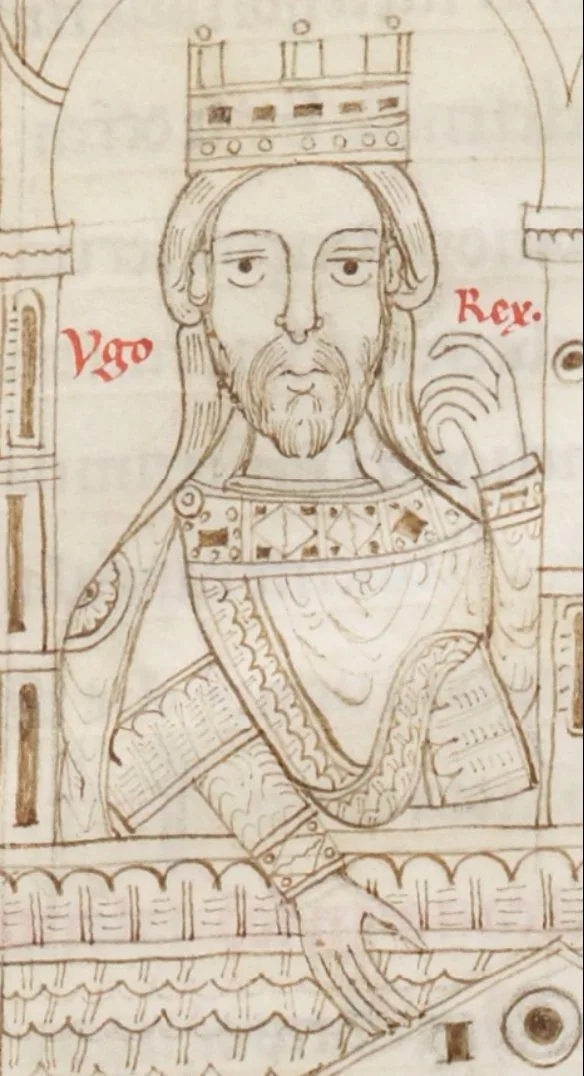

Hugh’s generous treaty of alliance permitted the Saracens to regain control over those alpine passes that led into Piedmont and Lombardy, from Mt. Genèvre to the Septimer Pass. The Saracens later assumed temporary suzerainty over the Monte Moro, the Simplon, and the Lukmanier passes as well. From their mountain basecamps, summer raiding parties regularly pillaged the Swiss countryside, striking at Chur and St. Gallen, in intervals, between c. 952-954. The Saracens even pillaged as far as the Bernese Jura in the late-950s.

How unjustly do you attempt to defend your kingdom, King Hugo! Herodes killed many innocent people, lest he be robbed of his earthly kingdom, but you let guilty people walk around free in order to get a kingdom…

Historical sources appear to corroborate a marked decline in Saracen activity soon thereafter. The death of Abd Al-Rahman III and the ascension of his son Hakam II to the throne may hold yet another explanation for the gradual withdrawal of Saracen forces from the Alps. Unlike his father, Hakam II pursued a course of peaceful relations with his Christian neighbors in Spain and France, while waging war on the Zirids and Fatimids in North Africa instead.

Evaluations & Lingering Questions

The French Orientalist Joseph Toussaint Reinaud (1795-1867), in his “Invasions des Sarrazins en France, et de France en Savoie, en Piémont et dans la Suisse” (1836), explored the cooperation between locals and the Saracens, finding that there was a high degree of association between Christians and Muslims. Notable exchanges of technologies, goods, and ideas took place between the respective populations as a direct consequence.

Some scholars have suggested that the Saracens introduced advanced methods in pine tar production and the cultivation of buckwheat into France as a result of their invasions. Others contend that the Saracens taught Europeans new techniques in the production of ceramics and textiles, and introduced the tambourine as a musical instrument. In Switzerland, the profusion of topographical names and surnames that seemingly allude to the historical presence of the Saracens has helped proliferate countless genealogical myths and folk legends in Valais and Graubünden. However, until more research and archaeological excavations are undertaken, they cannot all be disregarded.