Zurich’s first female photographer

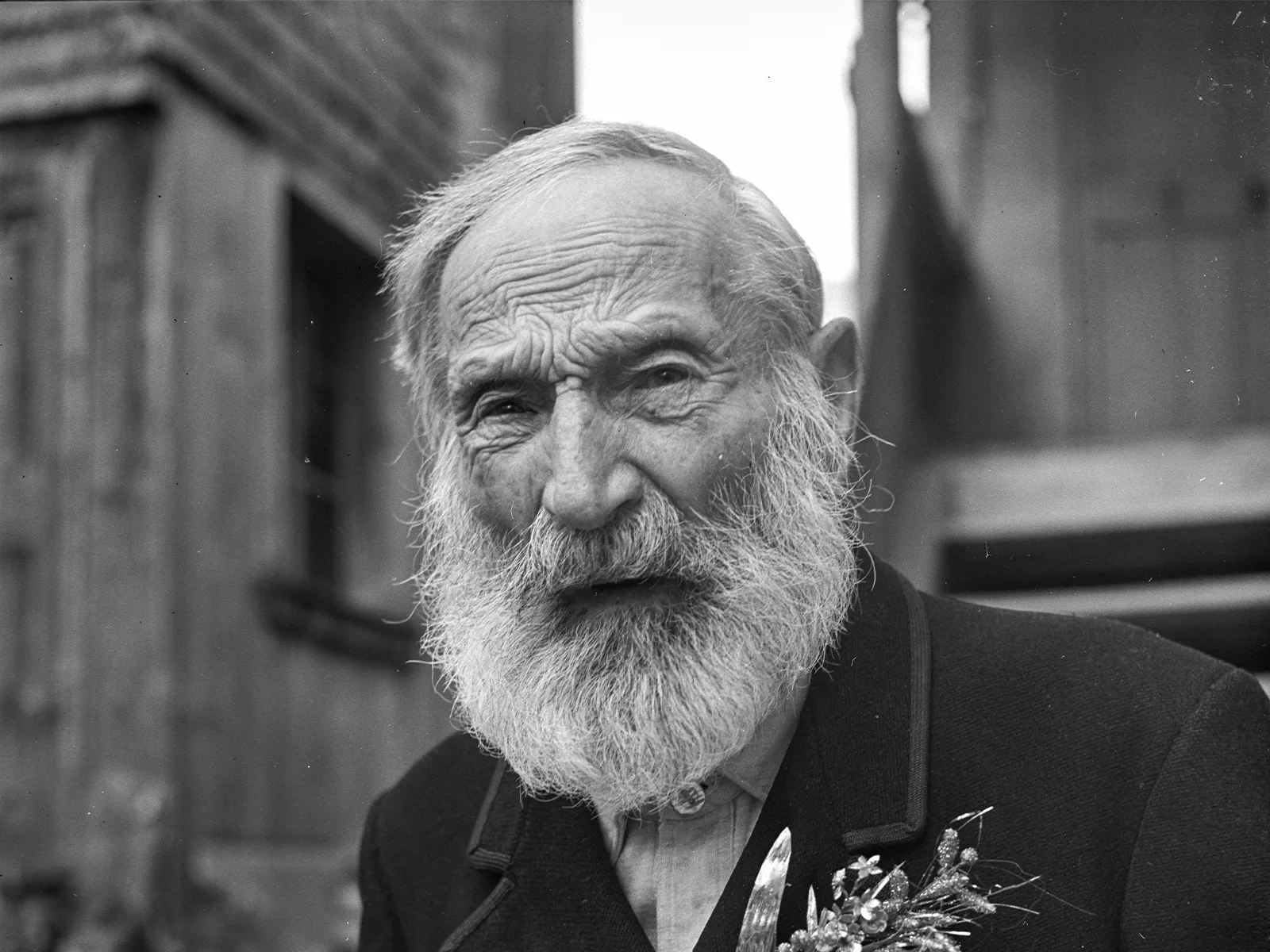

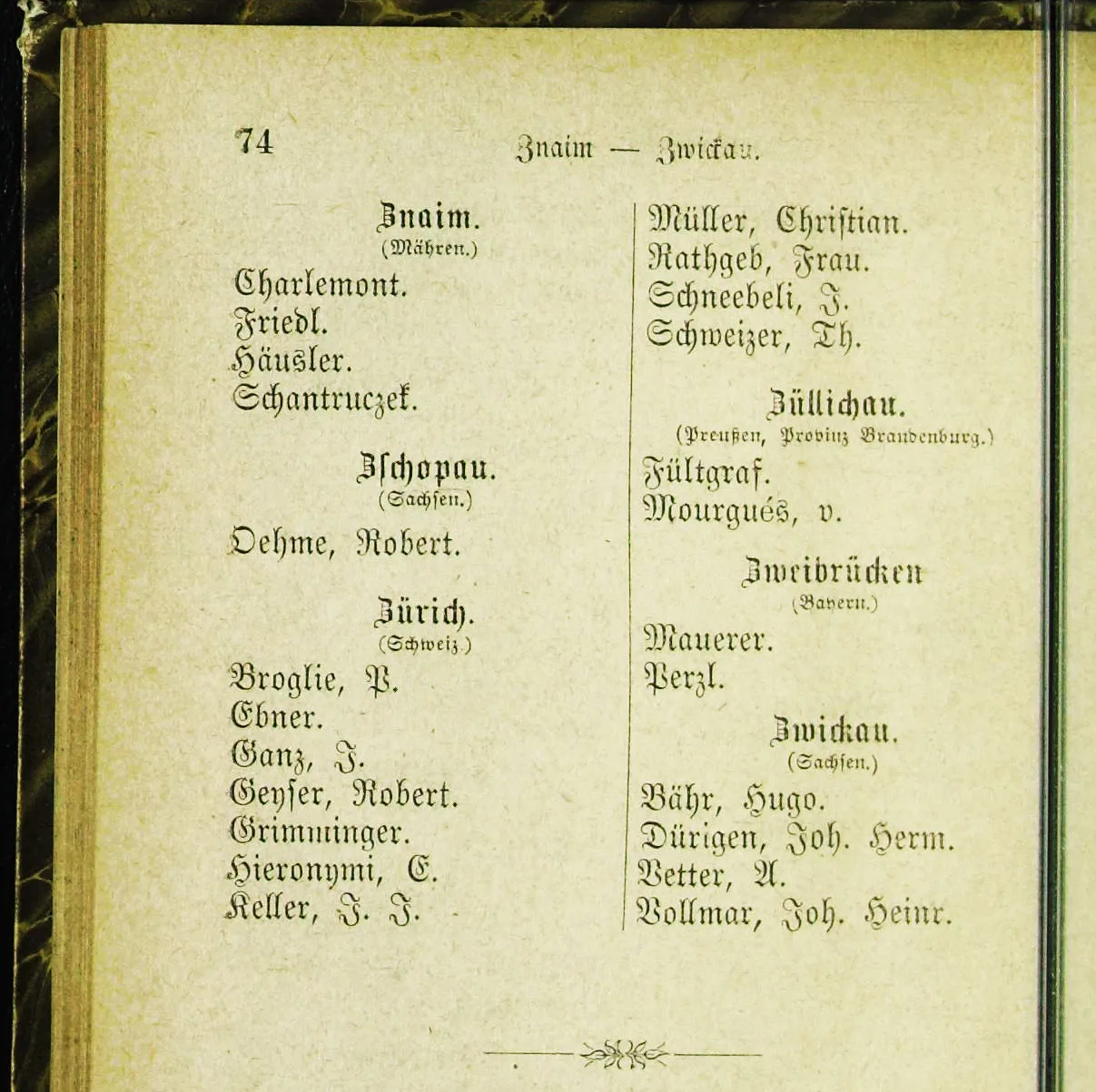

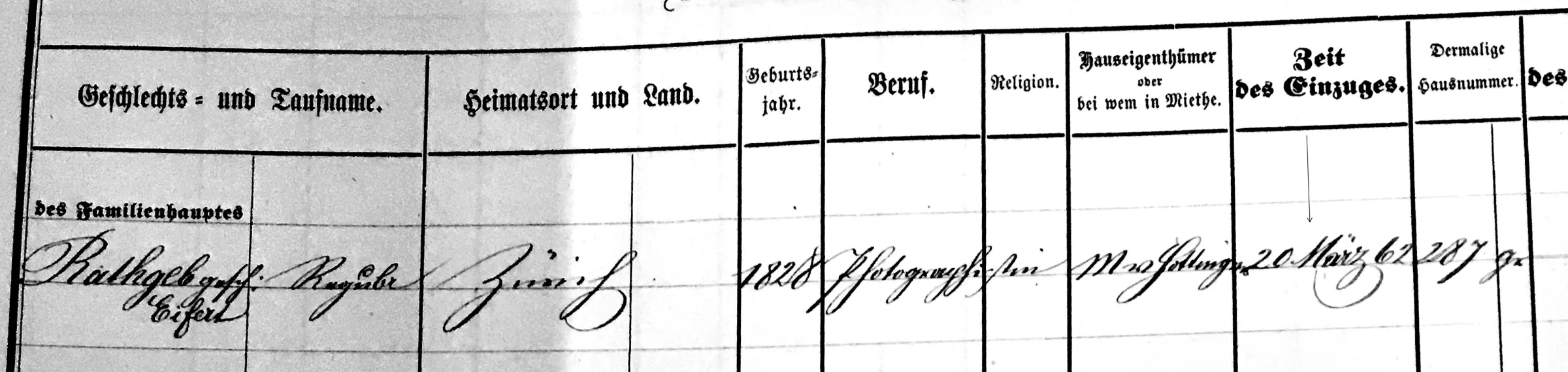

In its early days, photography was often seen as a male domain. However, some females were also among the pioneers of the new art form in the 19th century, including in Switzerland. One of them was Regula Rathgeb, who even wanted to set up her own studio.

A turbulent marriage

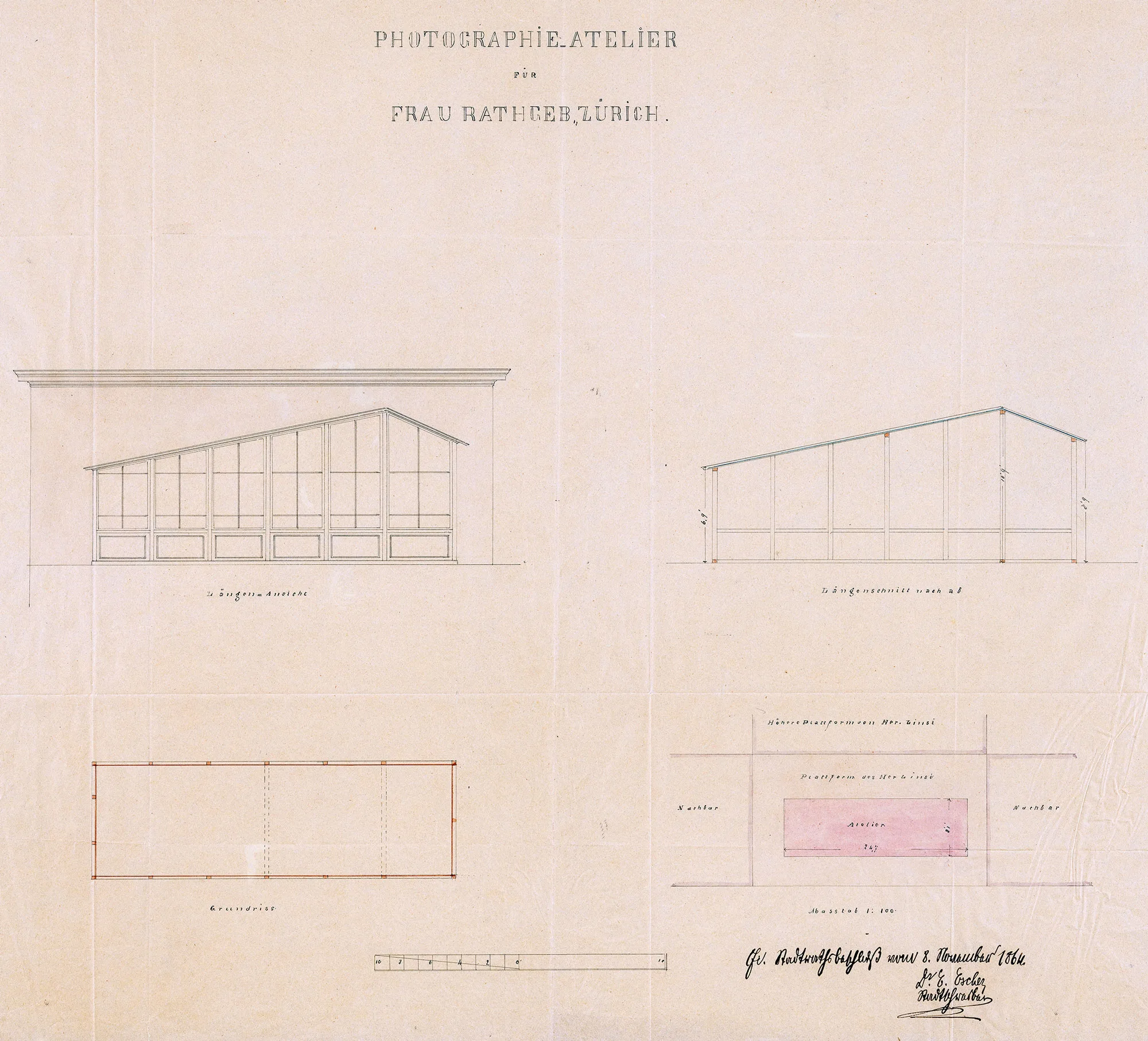

Project beset by obstacles

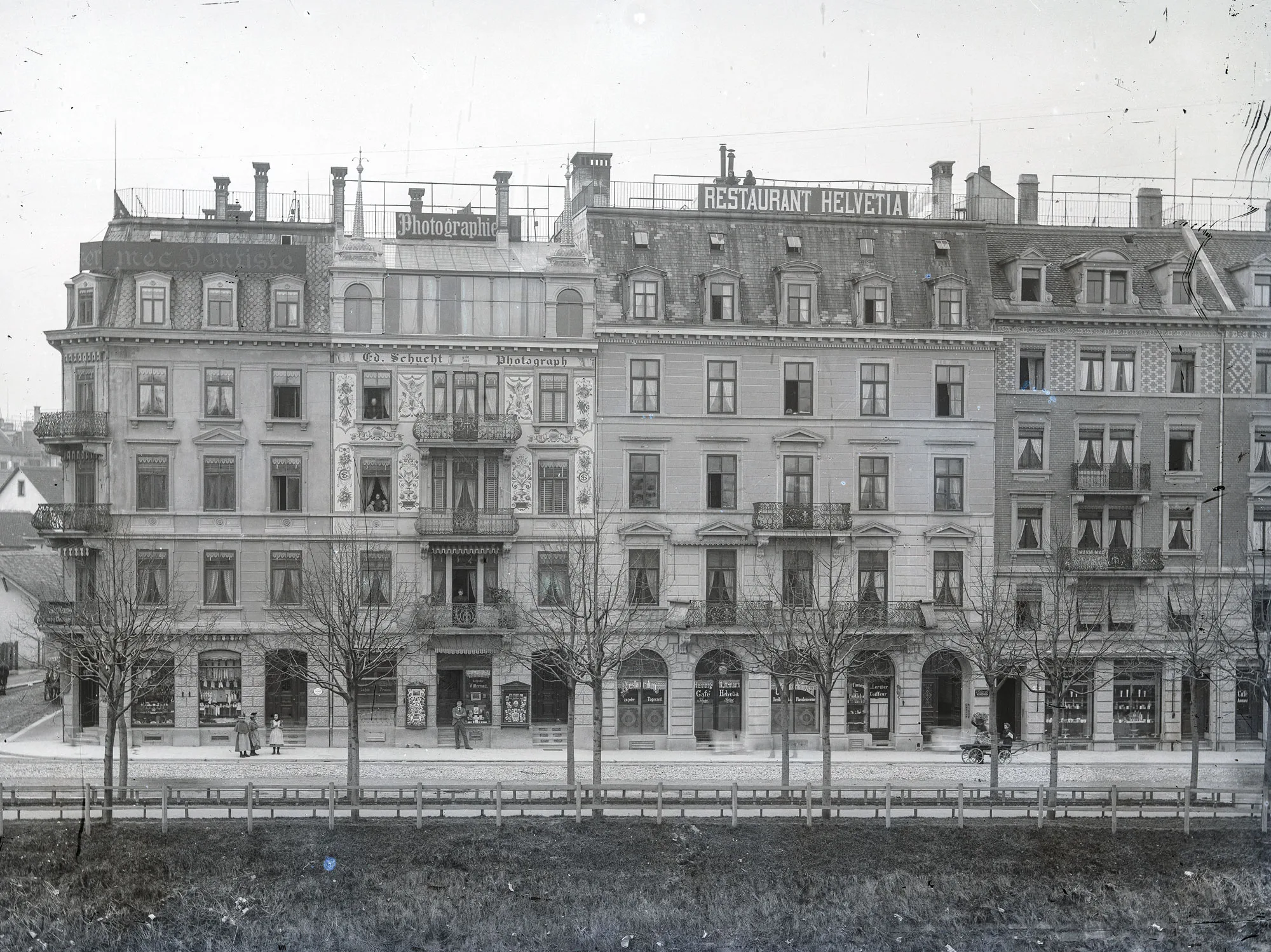

There were more than 100 photo studios in the city of Zurich from 1855 to 1915. They were used mainly for people and portrait photography. e-pics

As you know, the owner Mr Linsi acquired house no. 341 while the building code was coming into force and, in the face of objections, he significantly exceeded the maximum height for his house. We do not know what was behind this; now we have Mrs Rathgeb, a person we don’t know, who is putting a structure on the top of the building in question, against which we believe we have every right to object […]