How Swiss period rooms influenced American museums

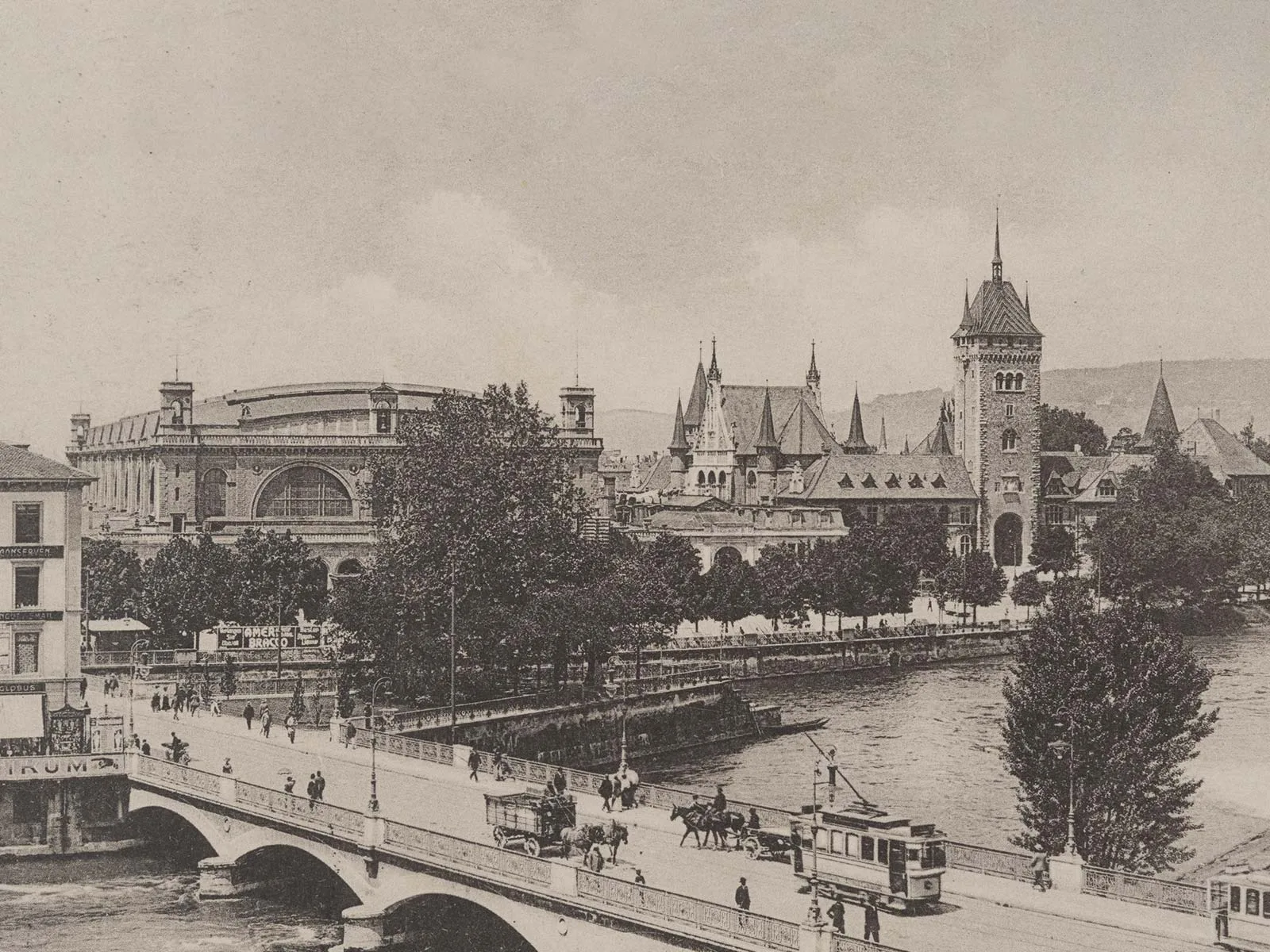

After it opened in 1898, the Swiss National Museum in Zurich and its period rooms served as an important model for museums in the United States.

When walking round the museum in Boston, one would hardly suspect that the Swiss National Museum was one of the main museums on which the institution was modelled, as today they are very different. The National Museum Zurich has retained and developed its original concept as a history museum with a national focus. Meanwhile, the MFA has evolved to become an international art and design museum.

These period rooms proved very popular in American museums over the course of the 20th century. By importing the model, the museum in Boston – and shortly afterwards the Metropolitan Museum in New York, which was also established in 1870 – played a pioneering role, as art historian Kathleen Curran has shown.

Around the turn of the 20th century, the directors in Boston were looking to have a new building erected to house their steadily growing collections. They sent a committee to Europe on a fact-finding trip to seek out suitable models for the architecture and the future presentation of the collections. The committee’s trip resulted in an extensive report, offering a snapshot of the European museum landscape, which was in turmoil at the time. The museum experts from the still relatively young country were particularly interested in the national museums that had come into vogue in Europe in the 19th century. The National Museum Zurich, founded in 1898, was held up as a particularly successful example.

The Musée de Cluny in Paris, which was founded in 1832 by a private citizen and soon bought by the state, was one of the early models, with its focus on French medieval and Renaissance art and artefacts. This elevated the status of architecture and craftsmanship. In fact, the museum was a presentation of random furniture and objects from the 16th century. It was a huge success with the public but a somewhat questionable construct from a historian’s perspective.

During the golden age of the Industrial Revolution, there was a desire to provide guidance in terms of taste and offer creative impetus by bringing together all manner of exceptional objects. Whole rooms were filled with display cabinets in which objects such as vases or glasses could be viewed side by side. The origin and history of the objects became secondary. This dry model of exhibiting collections in an educational way initially proved very popular. But visitor numbers soon plummeted, as these museums failed to tell engaging stories.

A new view of history to attract more visitors

It relied on the academic concept of ‘cultural history’ and also emerged primarily in the German-speaking countries. History was no longer told as a sequence of dynasties and wars; instead, the focus was on aspects of social and cultural history, from religion and science to art and the history of law. It was intended to convey a comprehensive and more authentic view of history. This new historiographical approach was made popular by books such as The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy published in 1860 by Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt.

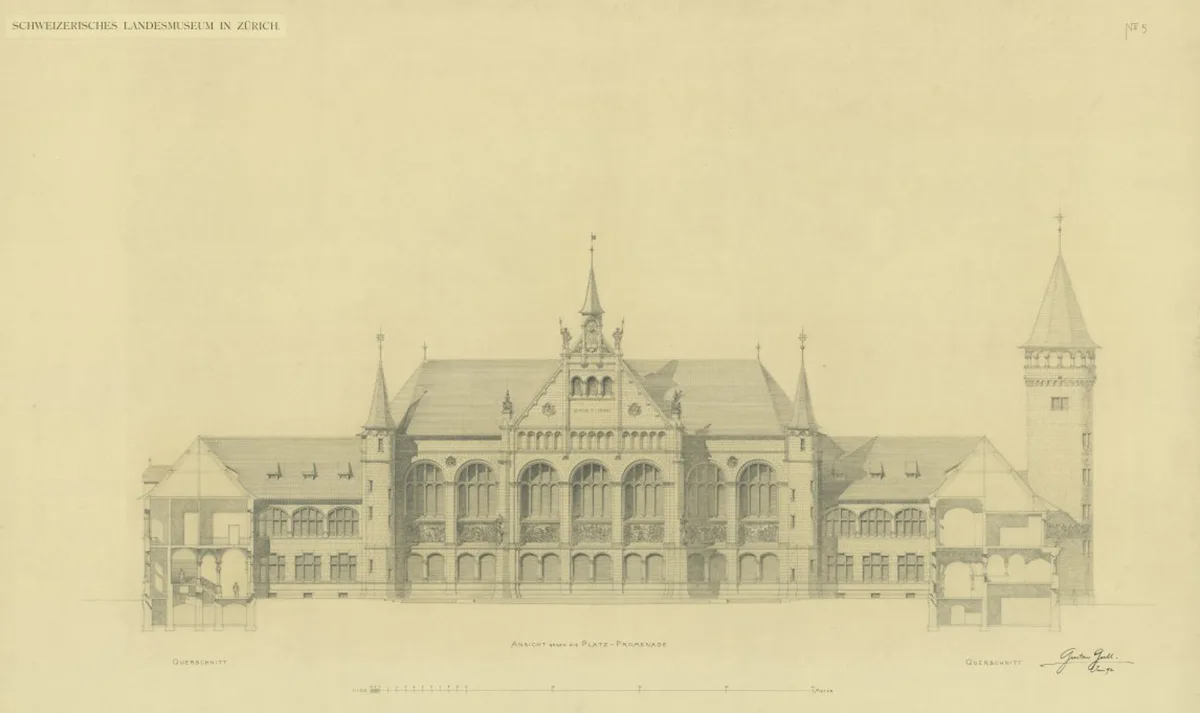

The formula developed at the National Museum Zurich went down well with the Boston museum directors, and subsequently a number of their colleagues. It was based on the engaging juxtaposition of different presentation forms, in particular of object display cases and period rooms. The Zurich Museum Commission – whose members included the subsequent founding director, Heinrich Angst, art historian Johann Rudolf Rahn, and Zurich mayor Hans Pestalozzi – worked with conservators and architect Gustav Gull to develop the building from the inside out as it were, on the basis of existing collections. This gave rise to a building that is an amalgamation of differing parts with an ‘armoury’ as its centrepiece.

As a result, the directors in Boston also had a wing constructed in their new building to house period rooms based on the Zurich model. They even included an example from Switzerland: the 16th-century Bremgarten Room. However, this was resold in 1930. The Metropolitan Museum in New York acquired the Flims Room, also known as the Swiss Room, in 1906. It can still be admired there today.

The convoluted history of this Swiss Room, as reconstructed by Paul Fravi in 1982, is a perfect example of how the appreciation of artistic and decorative art production changes over time. The panelled state room with its magnificent tiled stove was built around 1684 for the ‘little castle’ belonging to the Capol family in Flims. Today it is considered an outstanding example of its type. Yet, Rudolf Rahn, the very art historian responsible for founding the National Museum, described the décor of the castle in 1873 as ‘charming’ but not artistically exceptional.

The enthusiasm for such period rooms from Europe in a country that was still trying to find its own place in history took on a life of its own, particularly in the first half of the 20th century. For example, a series of cloisters were acquired from Europe by the Metropolitan Museum in New York, while wealthy Bostonian heiress Isabella Stewart Gardner opened a replica Venetian palazzo in her home city in 1903, replete with furniture, art and sculptures of different origins. Even the completely fantastical and crazy Hearst Castle (built from 1920) in California is rooted in this tradition.

By the 1970s, many of the period rooms imported from Europe had been altered, mothballed or sold on, prompted by societal shifts and a changing notion of history. There was some scepticism about what sort of society the primarily stately period rooms were supposed to represent, with artists such as Ed Kienholz particularly searing in their criticism. For his installation Roxys from 1960/61, Kienholz recreated a room from a 1940s Las Vegas brothel. Ironically, for now it hasn’t ended up in an American collection, but in a European one: at the Fondation Pinault in Venice.

The collection

The exhibition showcases more than 7,000 exhibits from the Museum’s own collection, highlighting Swiss artistry and craftsmanship over a period of about 1,000 years. The exhibition spaces themselves are important witnesses to contemporary history, and tie in with the objects displayed to create a historically dense atmosphere that allows visitors to immerse themselves deeply in the past.