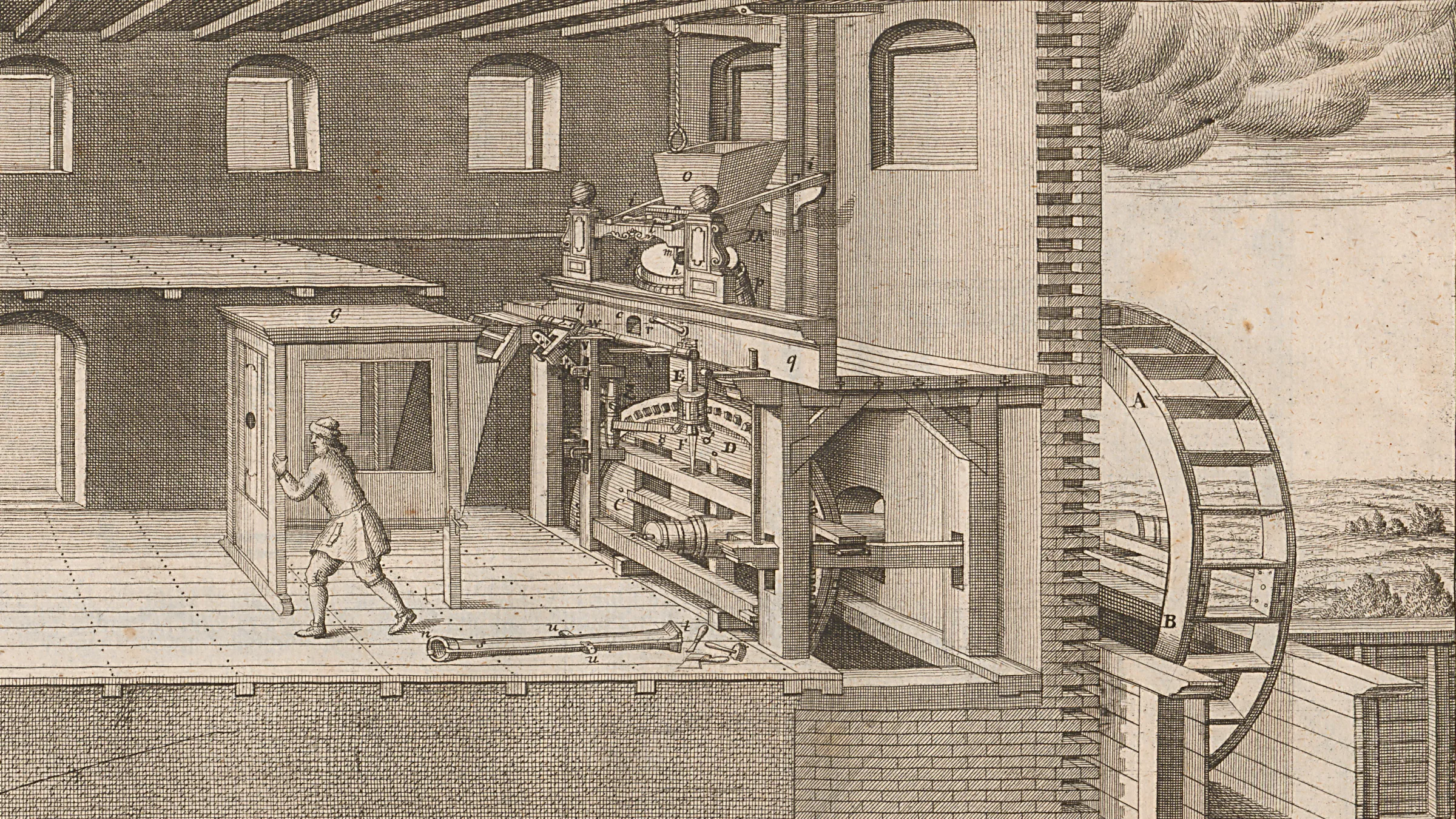

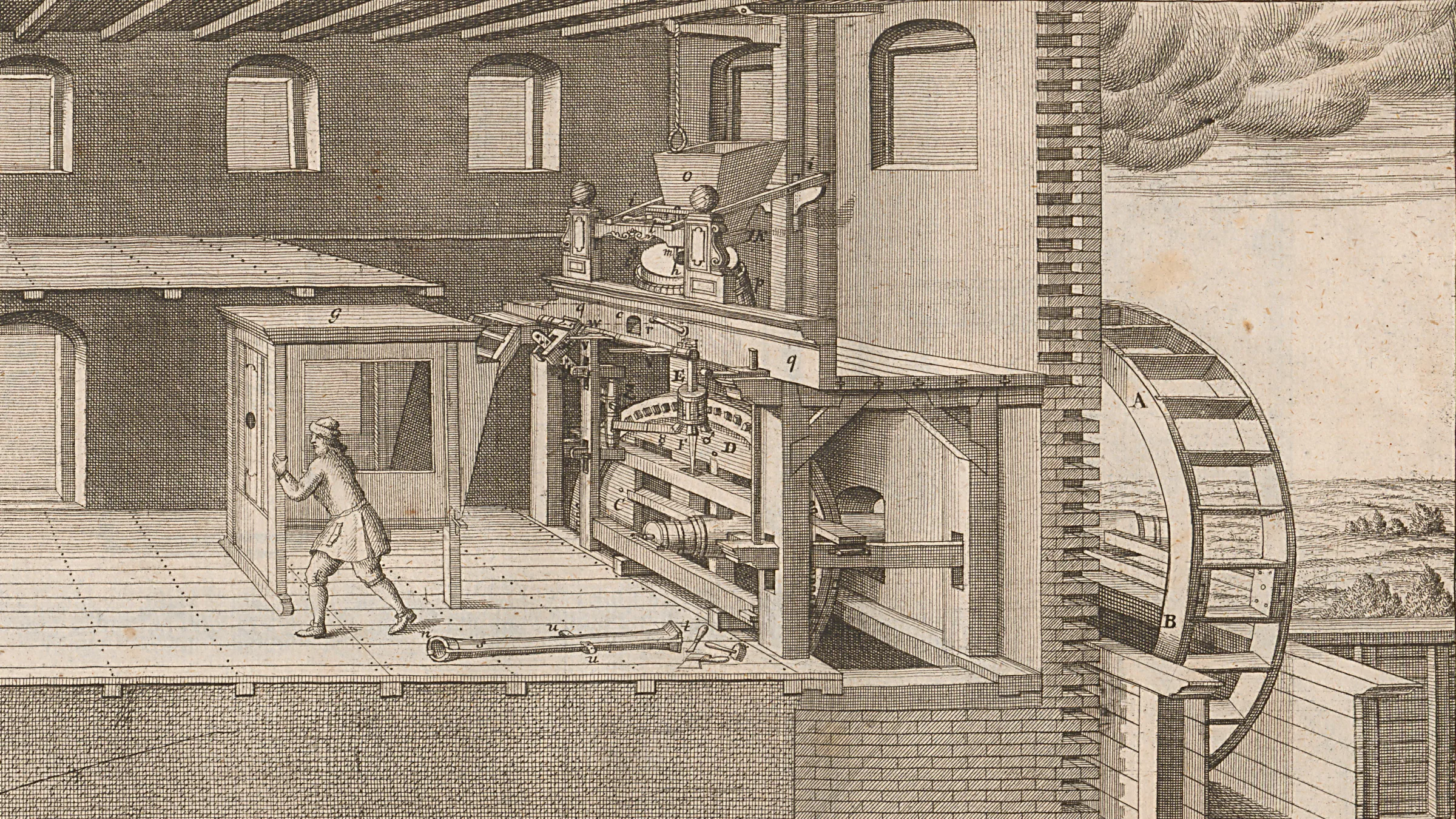

Powered by water, driven by ambition

Jonas Sandoz acquired the concession to operate mills in the caves of Col-des-Roches thanks to his political acumen. It was a successful venture – until he ran into financial difficulties.

Jonas Sandoz acquired the concession to operate mills in the caves of Col-des-Roches thanks to his political acumen. It was a successful venture – until he ran into financial difficulties.