The Neuchâtel deal

In 1856, the Swiss Confederation was poised to engage in war against Prussia. The reason for this was the Canton of Neuchâtel, which belonged to Switzerland, but was subordinate to the King of Prussia.

There’s never been a king in Switzerland! Or has there? Neuchâtel joined the Swiss Confederation as a separate canton in September 1814, but at the same time it had a royal ruler: the King of Prussia. Neuchâtel was thus at one and the same time both part of the fledgling nation of Switzerland, which had just received its national borders as they still exist today, and also a Prussian principality. This dual role was confirmed at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, and in the mid-19th century it inflamed a storm of passions at Lake Neuchâtel. So Switzerland never had a whole king, but perhaps a ‘quarter king’.

Revolutionary coup

When liberal revolutions broke out all over Europe in 1848, the opponents of the monarchy in Neuchâtel seized their chance and rose up. Led by Fritz Courvoisier and Ami Girard, around 1,000 armed insurgents seized the castle in the city of Neuchâtel and proclaimed the republic. King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia wasn’t pleased, but at that point there was nothing he could do about it. He was occupied with the revolutionary tendencies in his home country. He grudgingly accepted the new circumstances, but he didn’t give up his claim to the principality in western Switzerland. On the contrary – in 1852 he had his claim to Neuchâtel endorsed at an international conference in London.

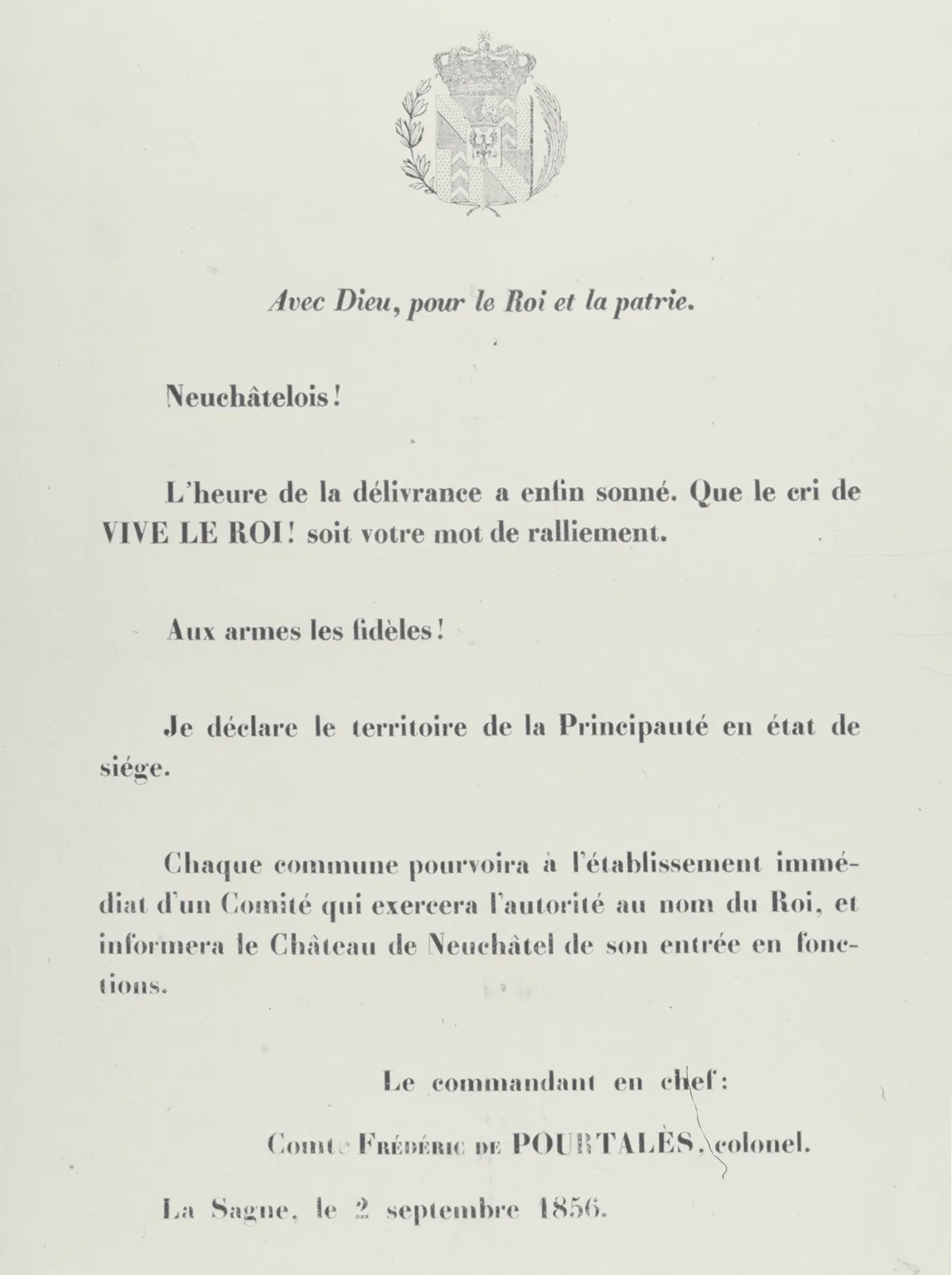

Royalist coup

Deprived of power, the Neuchâtel royalists operated in secret for the next few years. They met for covert gatherings, and waited for the right moment to restore what they believed was the rightful order. That moment came in September 1856. After the Prussian king had signalled in August that he would welcome a possible coup d’état, the royalists struck on 2 September. With a few hundred men they recaptured the castle in Neuchâtel. But the Republicans were far from defeated. With the backing of Swiss confederate troops, they quashed the uprising just a day later. Around 500 royalists were taken prisoner. They faced trial and the death penalty.

Now it had all gone too far for Friedrich Wilhelm IV, and the Prussian king demanded the immediate release of the prisoners. The Federal Council, now sucked into the conflict, rejected his demand. It also refused to impose an amnesty for the detained royalists. Unless Friedrich Wilhelm gave up his claim to the principality in western Switzerland. What an unacceptable proposal for a king! Prussia broke off diplomatic relations with Switzerland, and prepared for war. The Swiss, too, anticipated an armed conflict, and mobilised troops. On 27 December 1856, the Federal Assembly appointed Guillaume-Henri Dufour General of the armed forces. Under Dufour’s command, around 30,000 soldiers were relocated to the Rhine to secure the border.

Fully Swiss at last

The looming conflict came at a bad time for Europe. The Crimean War (1853-1856), in which France, the Kingdom of Sardinia, Great Britain and the Ottoman Empire had fought against Russia, had only just ended. The great powers, France and Britain, didn’t want a new conflict under any circumstances, and intervened. Ultimately, Napoleon III managed to dissuade the Prussian king from a military campaign. The attitude of the southern German population played into the hands of the French emperor. The majority of southern Germans were opposed to a Prussian campaign, which would have made the march through their territory and the logistical support of the troops difficult. Large sections of the Prussian army were also sceptical. Many soldiers didn’t see the point of the attack, because Neuchâtel was far away, somewhere in the south, and in their understanding it wasn’t really part of the Kingdom of Prussia. In the end, Friedrich Wilhelm called off the attack.

In mid-January 1857, the conflict was resolved and the interned rebels were released. After several rounds of negotiations, in May of that year the King of Prussia renounced his rights, but retained the (worthless) title ‘Prince of Neuchâtel’, which was roundly ridiculed by the British press in particular. The people of Neuchâtel didn’t care: they were fully Swiss at last.