Shared ailments, common cures: human and animal health in the Middle Ages

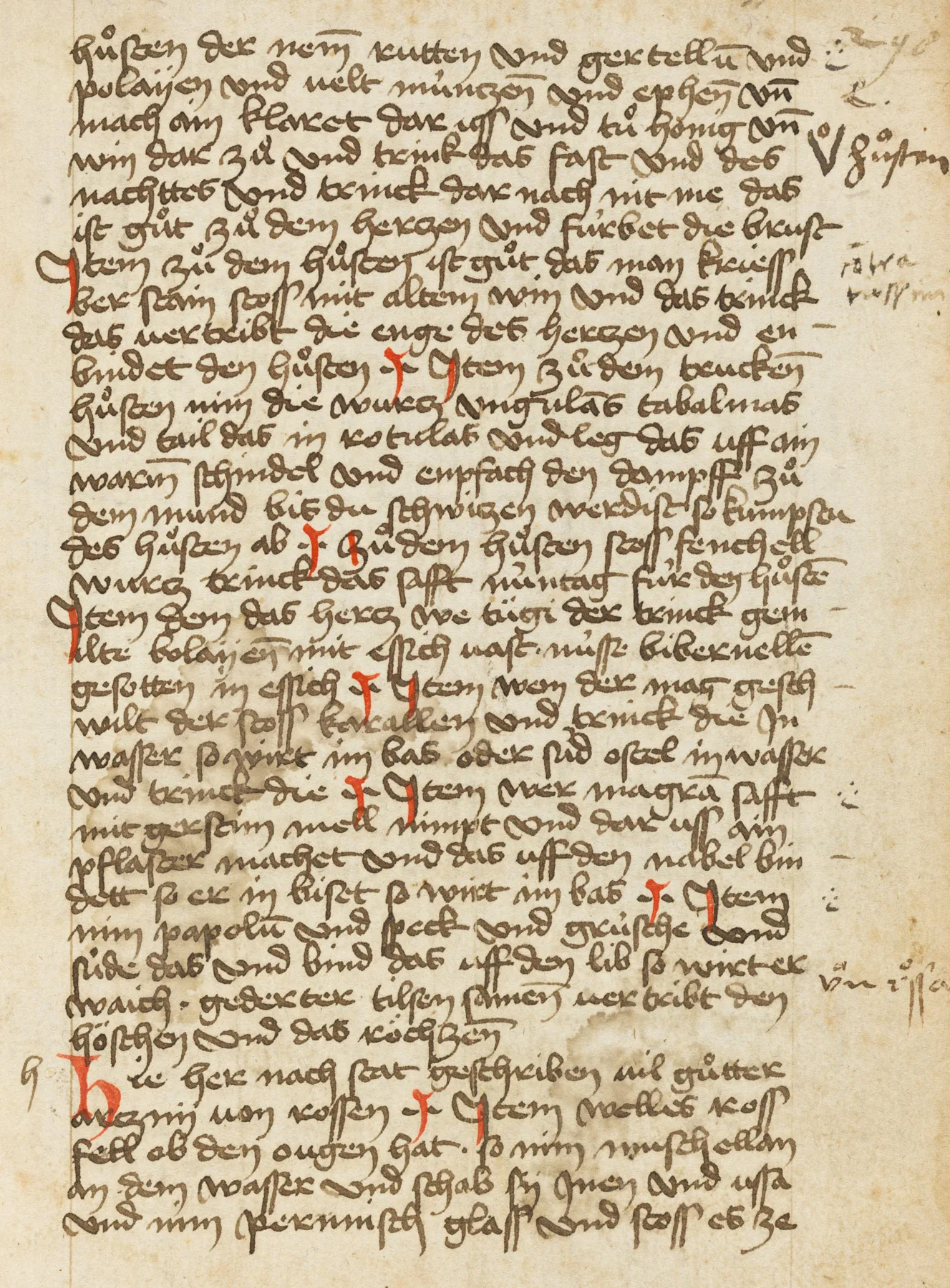

What can we learn from medieval cough mixtures and worm blessings? If nothing else, some unexpected inspiration about the shared history of human and animal health.

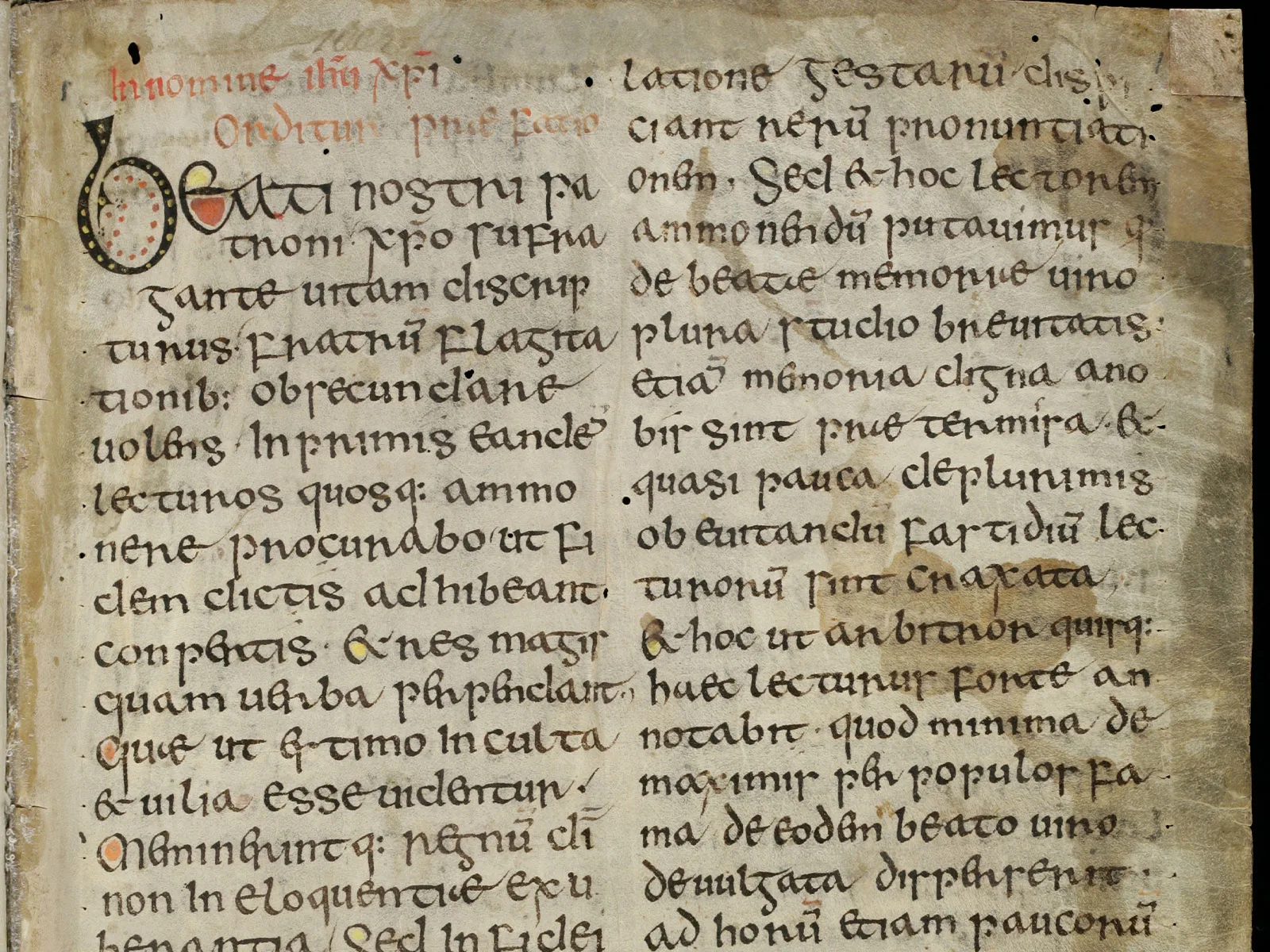

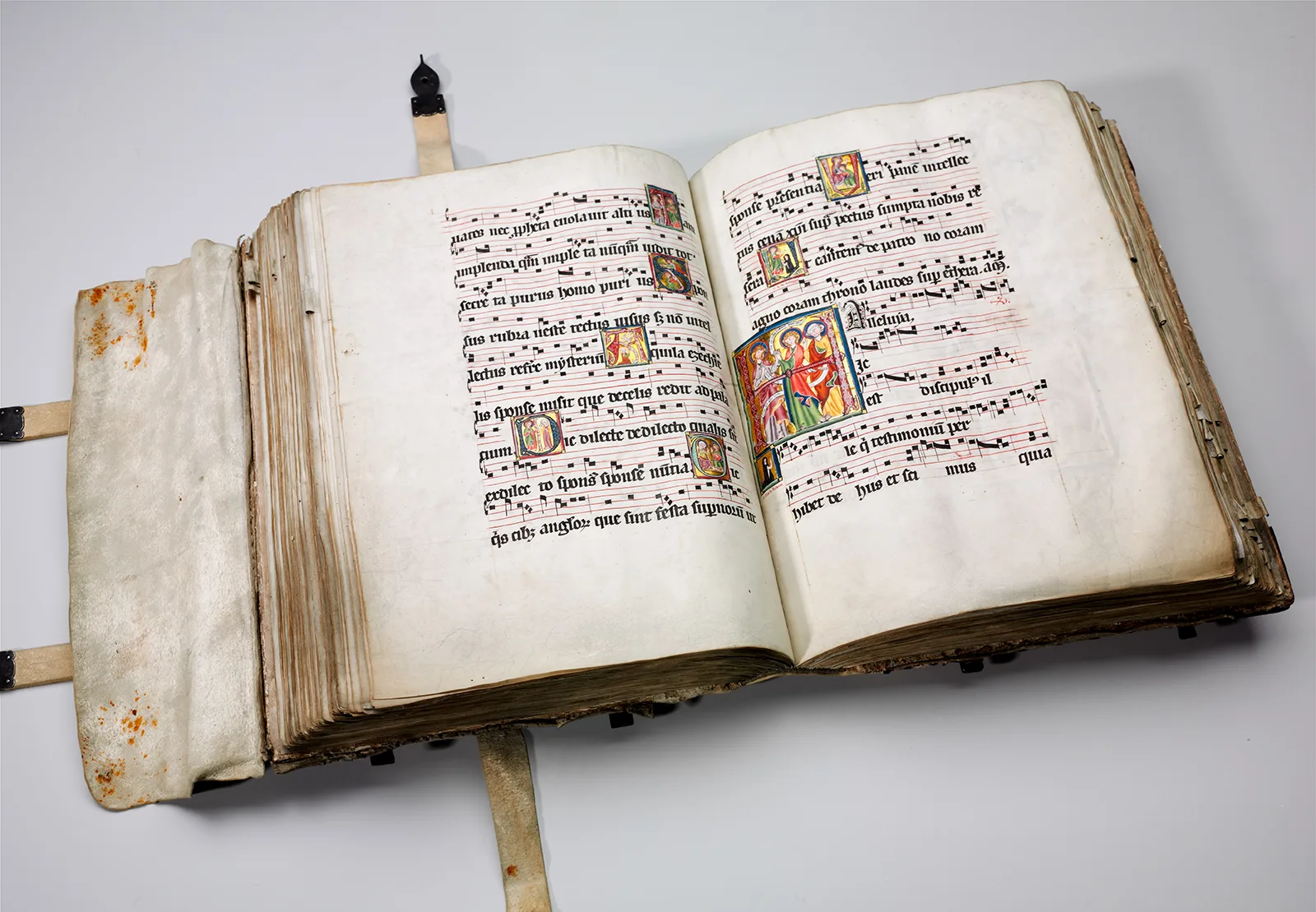

One book, many recipes

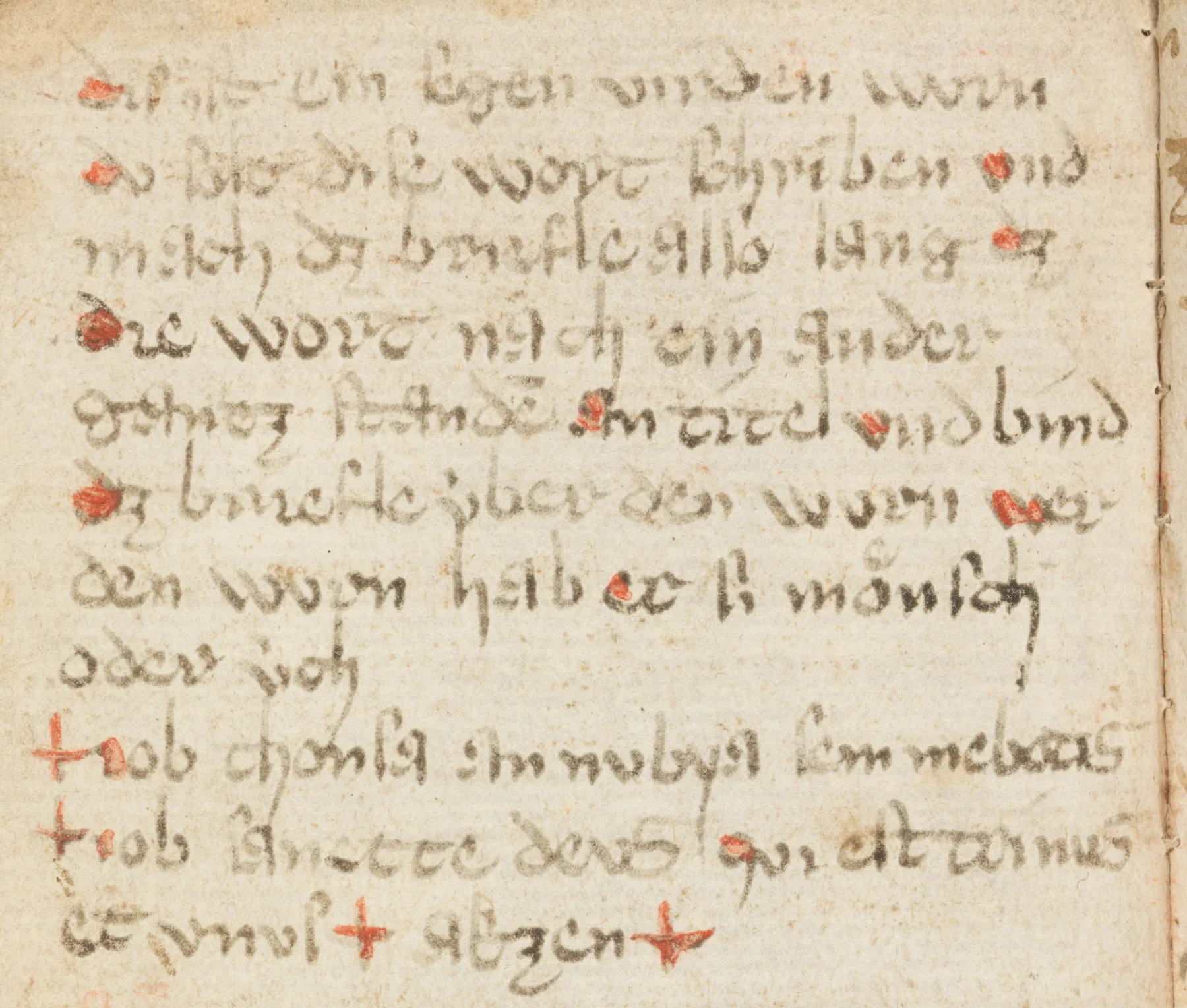

Once the worm is inside, only divine providence can help