The Battle of Murten

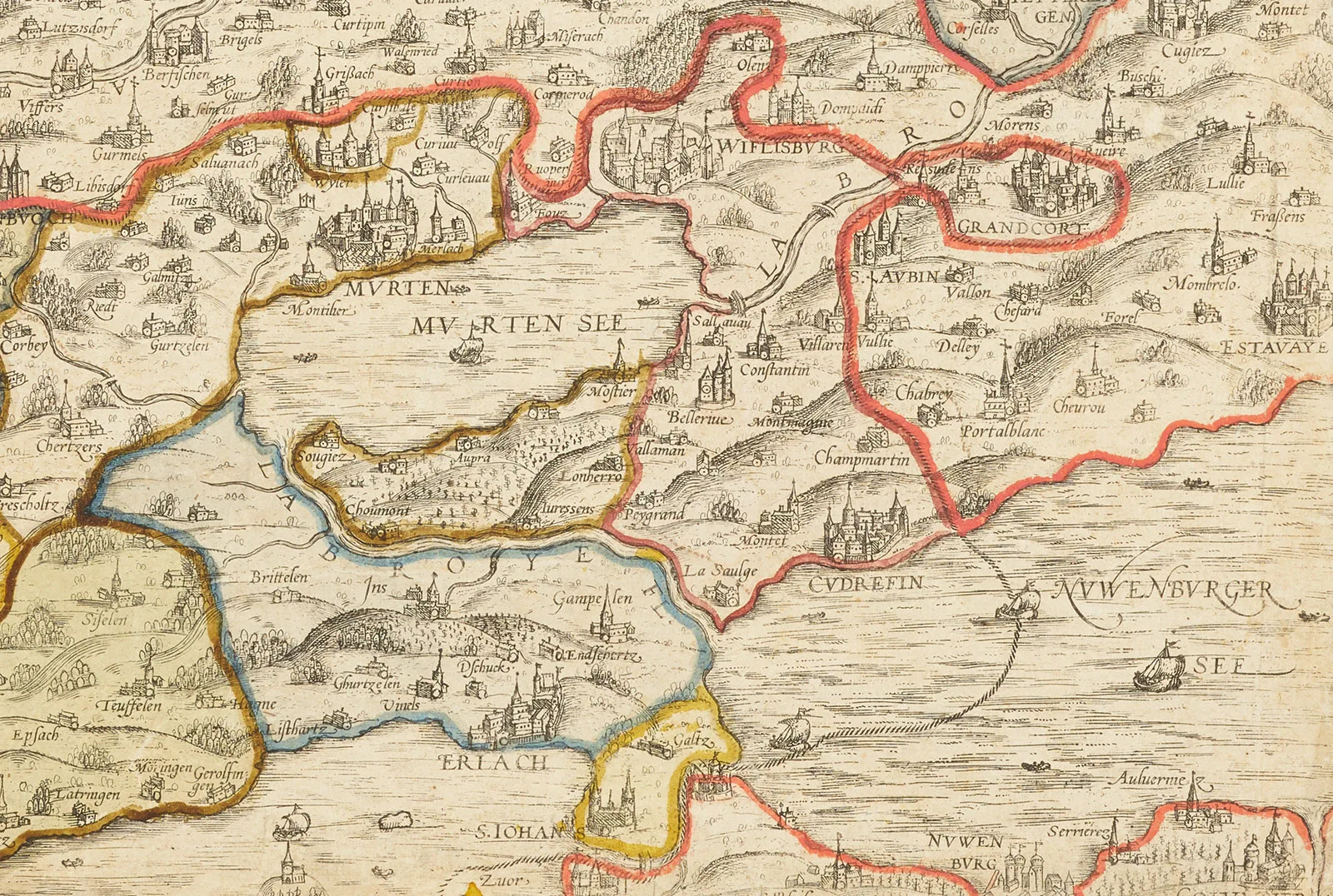

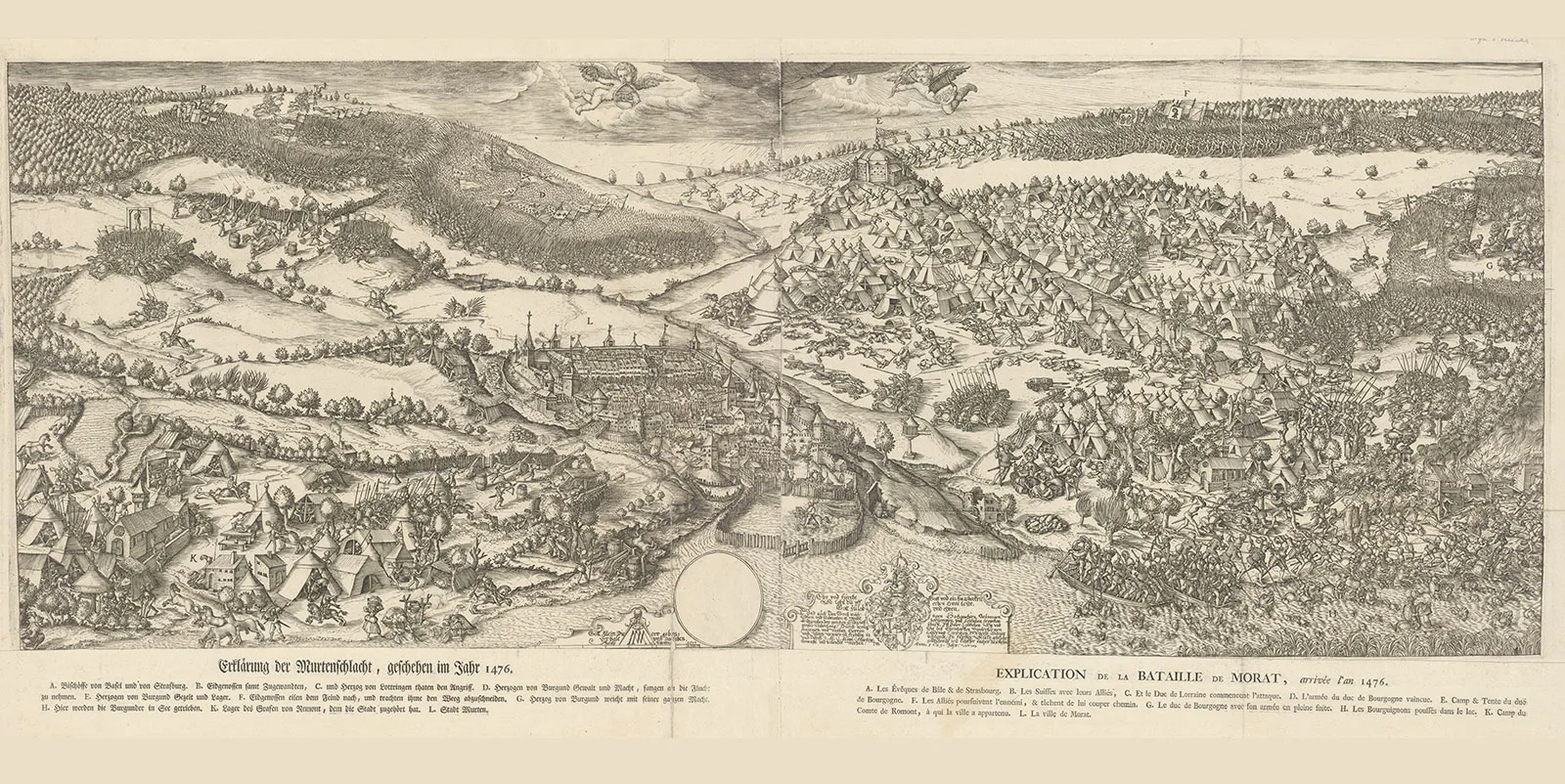

In the Battle of Murten on 22 June 1476, the Swiss Confederate army defeated that of Charles the Bold of Burgundy. The battle marked the beginning of the end of Burgundy as a major European power and became a cornerstone of national pride in traditional Swiss historiography.

If you attack that invincible people [the Swiss], you cannot win over them… You will never escape… It will be turned into a tale of how a mighty prince was overcome by rustics.

A deadly siege commences

You peasants! Surrender the city and castle. We will soon take the city and will capture you, kill you, and hang you by the neck.

The Battle of Murten

At Grandson his goods, at Murten his courage, at Nancy his blood.

Murten signals a new era

If we ever do battle in these places, be assured that we will not take the lake as our route of retreat!