Russian Egg Cult

Most years, Western and Eastern Christianity celebrate Easter on different weekends. In Russia the decoration of Easter eggs looks back on a long tradition in which the luxurious Fabergé eggs stand out as a highlight.

Easter without Easter eggs is practically unthinkable in Christian tradition. The Easter egg is one of the oldest symbols expressing belief in Christ’s resurrection. The tradition of exchanging eggs at Easter is believed to reach back to the third decade of the first century. The Easter egg symbolizes the creation of new life in Christ’s tomb represented by the eggshell, which is cracked open by the force of burgeoning life.

Decorated Easter Eggs in Russia

Easter is the pivotal religious holiday in Russia. For followers of the Russian Orthodox Church, giving painted and decorated eggs to family and friends at Easter is a very old tradition. They are inscribed with the words “Christos Woskresje”, meaning, “Christ has risen”, and are regarded as a symbol of new life. In Russia the painting and decoration of Easter eggs developed into a branch of folk art. Over time the materials and motifs became ever more intricate. Apart from Christian traditions and saints they featured historical as well as mythological themes. The Church supported the production of exquisite Easter eggs made of costly materials such as porcelain and precious metals and painted or studded with gems. During the First World War soldiers were given eggs decorated with Red Cross symbols.

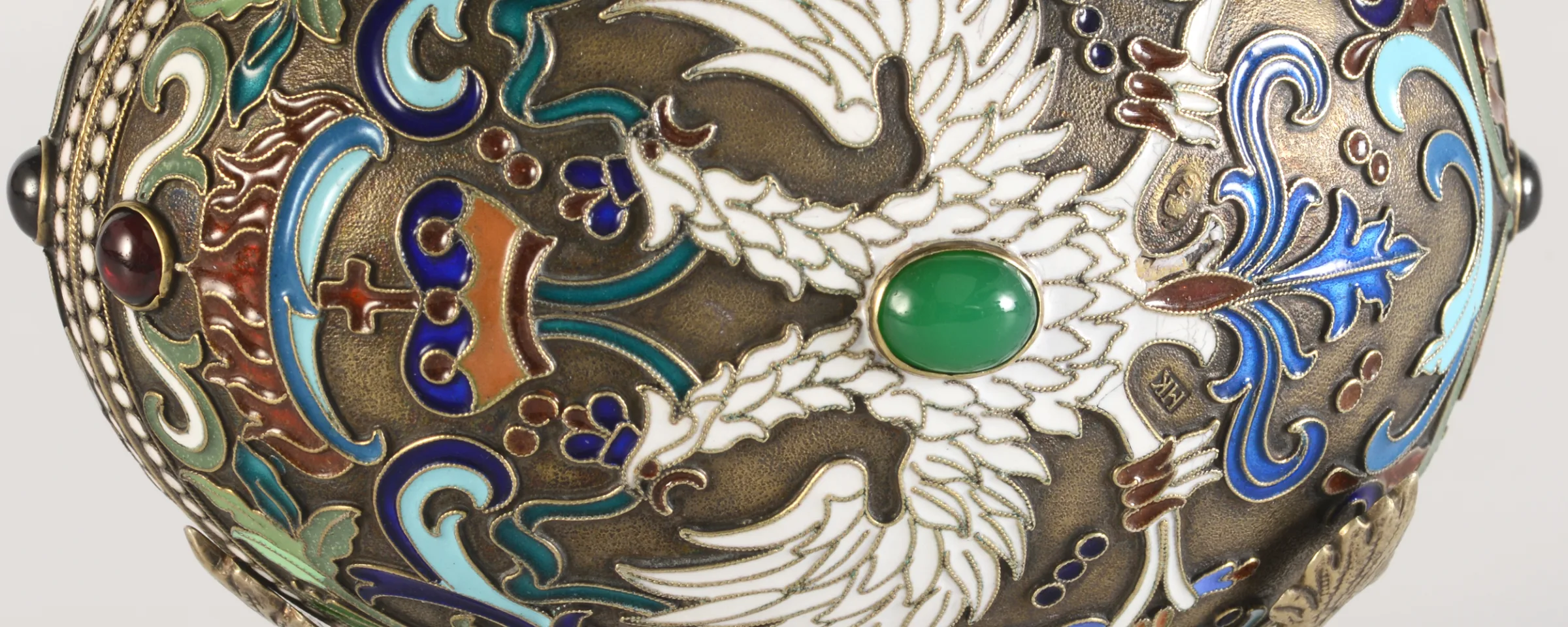

Fabergé Eggs for the Tsars

The most famous and valuable Easter eggs originate from the Saint Petersburg jeweller Peter Carl Fabergé (1846-1920). Fabergé produced his first Easter egg in 1885. Between 1885 and 1894 he created ten Easter eggs for Tsar Alexander III and between 1895 and 1916 a further forty eggs for Alexander’s successor Nicolas II, the last Russian tsar. Apart from the fifty imperial eggs, Fabergé created other masterpieces such as table clocks driven almost exclusively by clockworks produced by the Swiss company Moser & Cie from Schaffhausen. After the October Revolution the Bolsheviks seized all the art and jewellery works belonging to the tsar’s family, including the Fabergé eggs. In the 1920s and 1930s the communist government sold most of them off to Western dealers. Fabergé himself fled the country after the revolution and came to Switzerland where he lived unto his death in 1920.

The tradition of creating beautiful and elaborate Easter eggs is upheld in Russia to this day.

Peter Carl Fabergé, table clock with Moser clockwork in the shape of a Fabergé egg, 1893. Saint Petersburg. Silver, nephrite, gilded. Fondation Igor Carl Fabergé, Geneva.

Contested Date of Easter

Easter is one of the moveable feasts in the liturgical calendar. Not all Christian Churches celebrate Easter on the same date. Since the various Orthodox Churches follow the Julian calendar, the date of Easter in the West and the East can differ up to five weeks. But not this year: Easter Sunday is celebrated by all Christian denominations on 16 April.

Easter eggs, 1884–1900. Porcelain, enamel, granite and silver. Liechtenstein National Museum, Vaduz. Collection Adulf Peter Goop. Photos: Sven Beham.