Keystone/Str

Project 26

In 1990, P-26 was uncovered. The mission of this clandestine cadre organisation was to whip up, strengthen and maintain the public’s spirit of resistance in the event of Switzerland being occupied.

In February 1990, Schweizer Illustrierte magazine published an article entitled ‘The secret army of the EMD spies: 2000 men and women, trained in planting bombs and silent killing. People like you and me: the sinister special forces of the EMD spies’. Reaction to the rumour of the existence of a ‘secret army’ – at the end of the Cold War and hot on the heels of the microfiche scandal, which had deeply shaken confidence in the country’s public institutions – was strong.

The Swiss Parliament set up a commission of inquiry (PUK) to examine the events in the Federal Military Department (the EMD). The PUK’s EMD report submitted in November 1990 confirmed the existence of a secret cadre organisation whose purpose was to make arrangements for resistance.

Riots at a demonstration against government microfiche record-keeping in March 1990.

ASL / Swiss National Museum

Subsequent discussions centred in particular on the legality and potential hazards of P-26. A portion of the left was concerned that the emergency measures could have been directed against them. According to the fundamental concept of the organisation, dating from 1982, one of the scenarios in which P-26 would have gone into action was ‘internal upheaval due to blackmail, infiltration and/or the like’. The defining scenario, however, was that of foreign occupation – that is, a Soviet invasion.

The setting up of the secret organisation began in 1979. The name ‘P-26’ or ‘Projekt 26’ harks back to the drafting of the country’s overall defence plan of 1973. This plan included non-military aspects of national defence, and under Article 426 the plan addressed the issue of ‘Resistance in the enemy-occupied area’. But even before P-26, in the territorial forces and later in the special service there were preparations for resistance, undertaken in the wake of the seizure of power by the communists in Czechoslovakia in 1948, and especially after the suppression of the Hungarian uprising in 1956 and the Prague Spring in 1968.

Efrem Cattelan, alias ‘Rico’, was in charge of the management and organisation of ‘Projekt 26’. Under terms of strict confidentiality, ‘unremarkable average citizens’, male and female, were recruited, whose task it would be to organise and strengthen resistance in the event of occupation. Members received basic training in pistol shooting and conspiratorial behaviour. This included the setting up of dead letter boxes, and filature, the art of shaking off a pursuer. In special instruction courses, members were trained in more specific activities, which varied depending on the specialist groups involved. For example, while radio operators were introduced to encrypted message transmission, the engineering corps (the ‘Genisten’) practiced shooting and explosives use, and members of the ‘3M’ specialist group worked on the safe transport of people, material and messages (in German, ‘Menschen, Material und Meldungen’).

Efrem Cattelan, 1990.

The Library am Guisanplatz, Rutishauser portrait collection

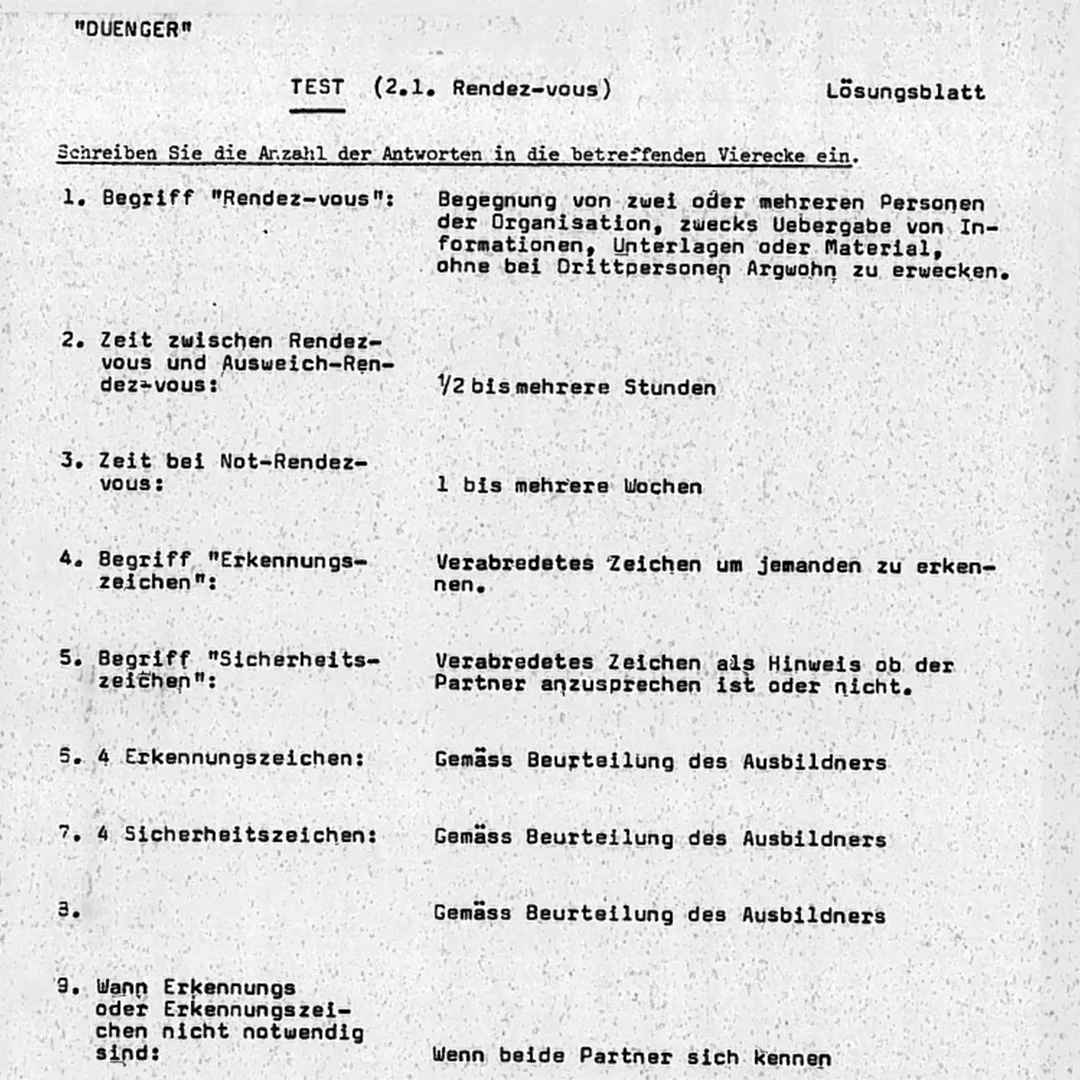

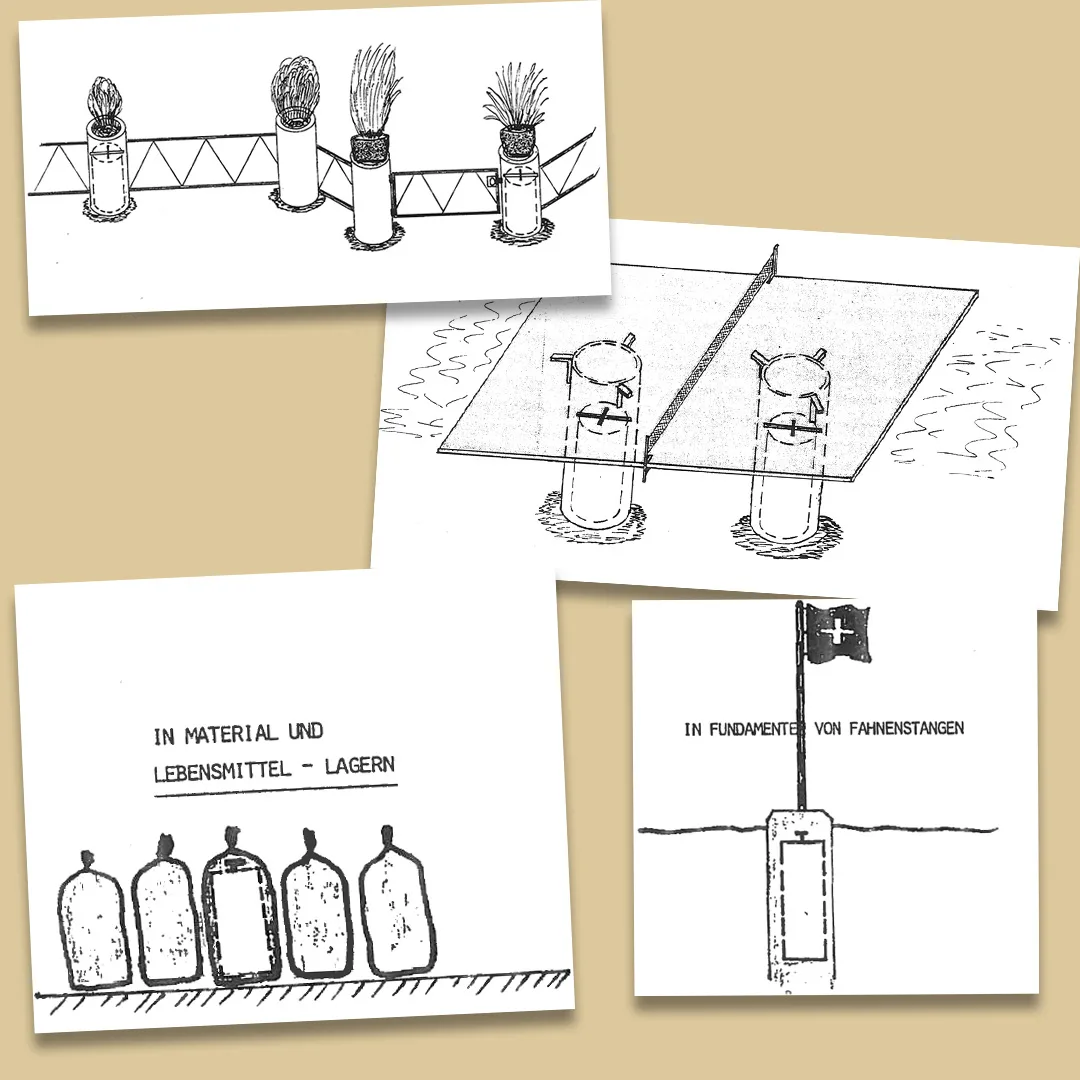

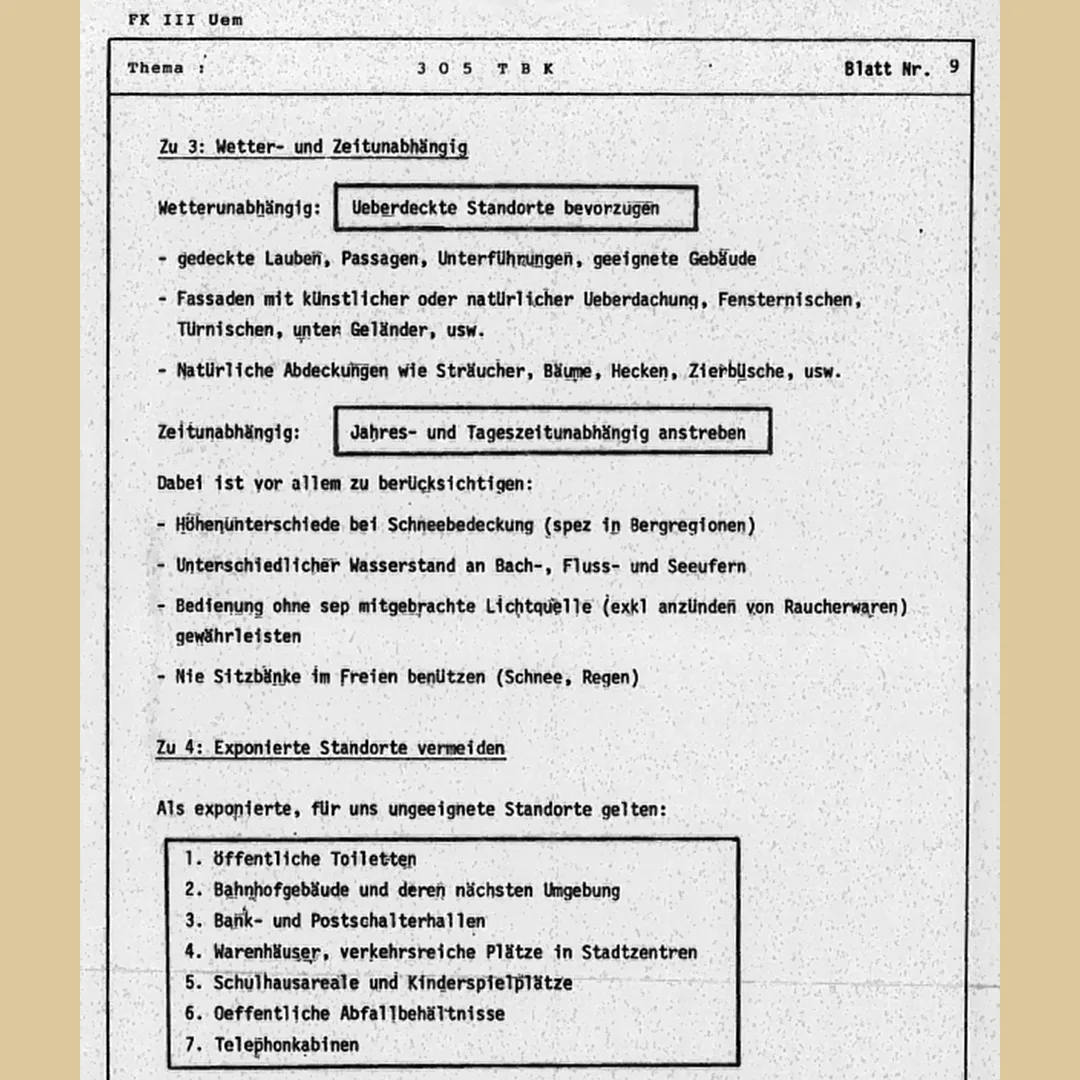

P-26 training documents on conspiratorial behaviour: solutions to test questions on the subject of ‘Rendez-vous’, options for camouflaged hiding places for materials containers, and tips for locations of what were known as ‘dead letter boxes’ for passing on messages.

Swiss Federal Archives

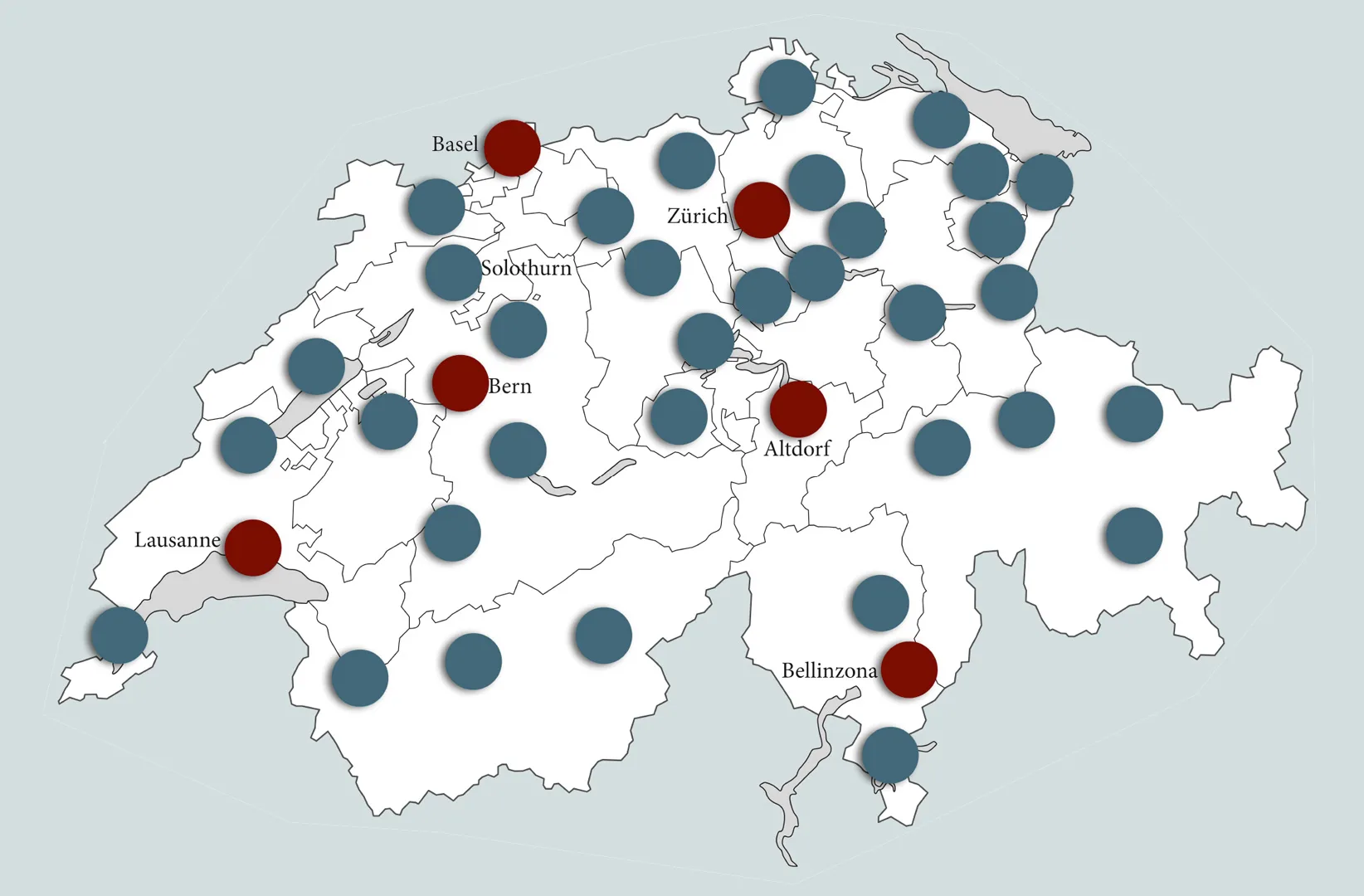

P-26 was organised in 40 regions throughout Switzerland. There were 34 ‘blue’ and six ‘red’ regions. The latter were located in economically, politically and logistically important areas, and had more personnel. For each of these 40 active regions, there was a sleeper region on the sidelines as a back-up plan, which would have been capable of taking over if the active region failed (Hydra principle). The regional groupings were kept separate. Each region consisted of several small groups, and members only knew each other within these individual groups.

In 1990 P-26 had around 300 members who had attended at least one course. Some women were also members of the organisation – but fewer than Efrem Cattelan would have wished for. He explained this with an ‘interesting social phenomenon’: ‘Even in an age of progressive emancipation’ it wasn’t possible for women to be absent from home for several days with only a vague reason given.

P-26 was financed out of Federal funds – from 1979 to 1990, it cost around 54.3 million francs. In an emergency, the group was to have been activated by the Federal Council.

Distribution of the 40 regions of the P-26 organisation. The red regions were more fully developed than the blue ones.

Map from Titus J. Meier, Widerstandsvorbereitungen für den Besetzungsfall. Die Schweiz im Kalten Krieg (Preparations for resistance in the event of occupation. Switzerland in the Cold War), NZZ Libro, 2018; Editing B. Maggio and N. Hänni.

P-26 was a clandestine project and its members were bound by an obligation of secrecy. This remained in force even after the organisation’s existence was exposed. It wasn’t until 2009 that the confidentiality requirement was lifted. Since then, a handful of individuals have gone public, while others have told at least their closest family and friends about their previous work in P-26. Some have chosen to remain silent. The membership list remains under seal until 2041.

Interview with Susi Noger, a former member of P-26, on the ‘Aeschbacher’ programme broadcast on 15 January 2015 (in German).

SRF