Smuggling between Switzerland and Italy

Smuggling has always been deeply rooted in Ticino’s collective memory, with large swathes of the population having used it to supplement their meagre income for centuries. Border stories from southern Switzerland.

From the young to the old, entire villages have been party to this illicit form of trading peddled over land and sea. The methods used have taken some astonishing forms. One of the root causes of smuggling was the social destitution in the border region, where a large portion of the population struggled to get by day to day. Working predominantly in agriculture, the locals saw smuggling – primarily of tobacco, coffee, alcohol and various foods – as welcome additional income.

Switzerland: the land of low prices

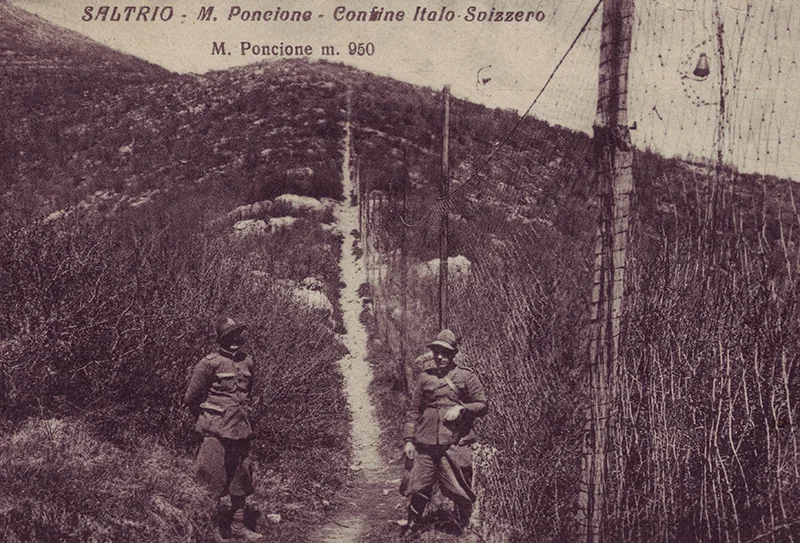

The dominant direction of travel for smuggling from Switzerland to Italy was above all a result of the two countries’ customs policies. While the Italian government imposed protective duties as early as the 1870s, its Swiss counterpart held fast to the principle of free trade. This led to significant price differences: in 1897, one kilogram of sugar cost the equivalent of 0.6 lira in Switzerland and 1.5 lira in Italy, while the price for a kilogram of coffee was 3.5 lira in Switzerland compared with 5.5 lira for its southern neighbour. This meant that the smugglers picked up on the border almost exclusively belonged to Italy’s border communities. The Italian border guard (Guardia di Finanza) had a costly metal fence (ramina) installed along the border to prevent the smugglers from entering the country illegally.

From Switzerland’s point of view, however, export smuggling was simply a crude form of export and was generally benignly tolerated by the locally authorities. Many Swiss businesses on and near the border essentially made their living on the goods delivered by smugglers. These fundamentally different views between the two countries regularly sparked bilateral tensions.

The border fence near Poncione d’Arzo. Photo: G. Haug collection

The «smuggler submarine» fascinated both the border guards and the local children. Photo: Archivio di Stato del Cantone Ticino (State archive of the canton of Ticino)

Pedal-powered submarine

The smugglers had to come up with some inventive ideas to sneak the goods past the border guards unnoticed. In one truly spectacular discovery in 1886, the Guardia di Finanza uncovered a cheese wheel at Chiasso station whose hollowed-out interior was stuffed with 300 kilograms of tobacco products. The smugglers’ methods grew more intricate over time. In November 1948, the Italian border guards found a submarine on the banks of Lake Lugano, a miniature model of which is now on display at the Swiss Customs Museum. It was three metres long and could transport up to 450 kilograms of goods. Most astonishing of all was the means by which the boat was driven: it was powered by foot pedals installed inside the boat and connected to its propeller.

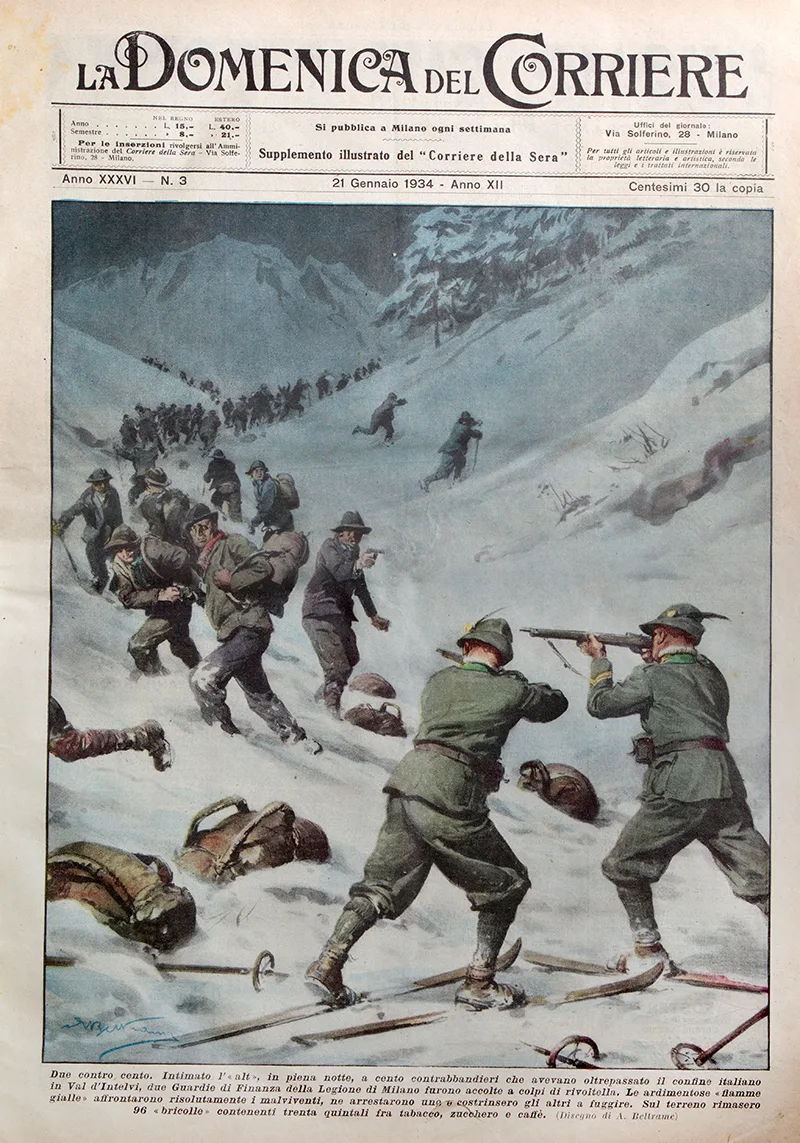

In most cases, the smugglers had to embark on exhausting treks over the so-called green border in groups of three to ten people, carrying a bricolla – a woven wicker container similar to a rucksack. The smugglers made themselves special shoes out of fabric (peduli) to allow them to navigate the woods as silently as possible. Each band of smugglers had its own leader who would go at the head of the pack and act as scout, armed with clubs, knives and even small sickles (falcetti). If the leader of the band discovered a border patrol, he was responsible for warning the other members of the group or giving the order to retreat. In some instances, the border guards – who often led a rather lowly existence themselves stationed at remote border posts – proved open to bribery. In such cases, it was the leader of the band who would negotiate the payment. Even if the smugglers fundamentally wanted to avoid any physical confrontation with the border guards, they regularly ended up in vicious skirmishes.

Smuggling didn’t just involve people, boats, carts and trains as modes of transport – even dogs were loaded up with goods. As well as the small groups consisting of three to ten people, smugglers could also form entire convoys. One of the biggest groups ever discovered had no fewer than 131 people and was spotted by an Italian border patrol between Arogno and the Val d’Intelvi in 1934.

Smuggling should not just be considered a romantic form of cross-border goods trafficking, however. Between 1868 and 1894, roughly a quarter to a third of the tobacco produced in Ticino was smuggled over the border. Small tobacco processing businesses in the area surrounding Chiasso were entirely dependent on the smuggling trade. It must not be underestimated how important smuggling was for the region’s local economy.

The Swiss Customs Museum

You can find out more about smuggling between Switzerland and Italy at the Swiss Customs Museum in Cantine di Gandria. The museum sells copies of the book Das Schweizer Zollmuseum (the Swiss Customs Museum, available in French, German and Italian), which provides more background on smuggling and chronicles the museum’s history.

Open daily from 1.30 p.m. to 5.30 p.m. from 7 April to 20 October 2019.

Admission: CHF 5/2.50 (6 to 16 years); free for under 6 years

Smugglers making their peduli in Scudellate (Muggio valley). Photo: Archivio di Stato del Cantone Ticino (State archive of the canton of Ticino)

Smuggler dog carrying a bastina. Photo: D. Ravasi collection

Picture taken from the Domenica del Corriere newspaper depicting the group of smugglers discovered in Val d’Intelvi in 1934. Photo: La Domenica del Corriere, 21 January 1934