Steel helmet on!

Some soldiers who enlisted to fight in the First World War still wore caps, though the army soon realised that only steel helmets could protect heads against shrapnel injuries.

At the beginning of the 20th century, a new development emerged in warfare that immeasurably increased the destructive power of weapons and explosives. The battle tactics, but especially the soldiers’ equipment, lagged behind this development. As late as 1914, men still went to war with coloured uniforms and shiny helmets or shakos – a head covering made of felt and leather. In the hope and belief that this would be a conventional and brief war, little attention was paid to the physical protection of the soldiers. Things turned out differently, with battles of attrition of unprecedented proportions and trench warfare. Only days into the war, the warring parties discovered first-hand the disastrous effect of prolonged shelling with fragmentation and shrapnel grenades. Around 80 percent of wounds were attributable to artillery fire, a quarter of these to head injuries with a fatal outcome in most cases.

Skull cap and Brodie helmet

France was the first to react and designed a skull cap, which soldiers wore underneath their Kepi caps. Head injuries were reduced by 60 percent. This was followed by the creation of the familiar Adrian helmet. The British also developed a simple Brodie helmet made of thick manganese steel, which was issued to the troops from November 1915. On the German side, the Army Detachment commanded by General Hans Gaede designed a headpiece consisting of a two-kilogram steel plate, which was mounted on a leather cap and went down in history as the Gaede helmet. Two German engineers developed a steel helmet made of tempered chrome-nickel steel with eye and neck protection, which was first issued as a batch of 30,000 helmets in February 1916. This helmet offered the most effective protection of all the types of headgear known up to that point.

Soldiers equipped with the Gaede helmet, 1915. Photo: reddit.com

And Switzerland?

In Switzerland, the army leaders followed developments on the front lines with interest. They were well aware of the heavy losses caused by shrapnel injuries and started to think very early on about effective protection. They turned to Neuchâtel artist Charles L’Eplattenier, a famous Swiss painter and architect. He created a series of prototypes – all designed based on artistic considerations. A 700-gram model available in two variations and with different colours went into small-scale production, with 100 helmets sent to the troops for testing. However, ballistic tests were unsatisfactory and when the required 350 tons of nickel steel sheet arrived from abroad it became apparent that the strongly rounded moulds of the helmet could not be produced on an industrial scale.

Prototype of the Model 17 steel helmet by Charles L’Eplattenier, around 1917. Photo: Swiss National Museum

A soldier wears the Model 17 steel helmet with chip guard. Photo: Swiss Federal Archives

After an unsavoury debate with accusations flying back and forth, a different team designed another model. The new helmet was officially introduced as Model “M 18” on 12 February 1918. It was sprayed olive green and had a smooth surface. But it was not long before this model too revealed flaws. On moonlit nights the helmet was visible from 300 paces and after it rained the helmet glistened in sunlight. In addition, when riding a horse or a bicycle, the airflow created whooshing and whistling noises, and in cold weather there would be an unpleasant draught, which meant that the soldier had to plug the air holes or wear a cap underneath the helmet. In 1943, the smooth, olive-green surface was equipped with a rough coating of anthracite-coloured sawdust and glue, which was intended to disguise it better.

Kevlar follows steel

Since the helmet had other shortcomings as well – it did not sit perfectly on the head and had to be worn back to front when the soldier was shooting so that he could aim properly – the army began working on a new model by the 1960s. This was introduced from 1976 as the “M 71”. It was field-green as usual but now available in five sizes. The Swiss army still uses the M 71, but for some time now it has gradually been replacing this with a next-generation helmet: the bullet-proof 04 helmet made of Kevlar.

Model 18 helmet, sprayed field-grey, from 1918. Photo: Swiss National Museum

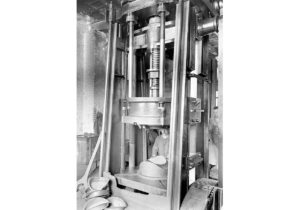

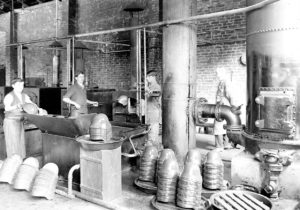

Production of the Model 18 helmet. Photos: Swiss Federal Archives