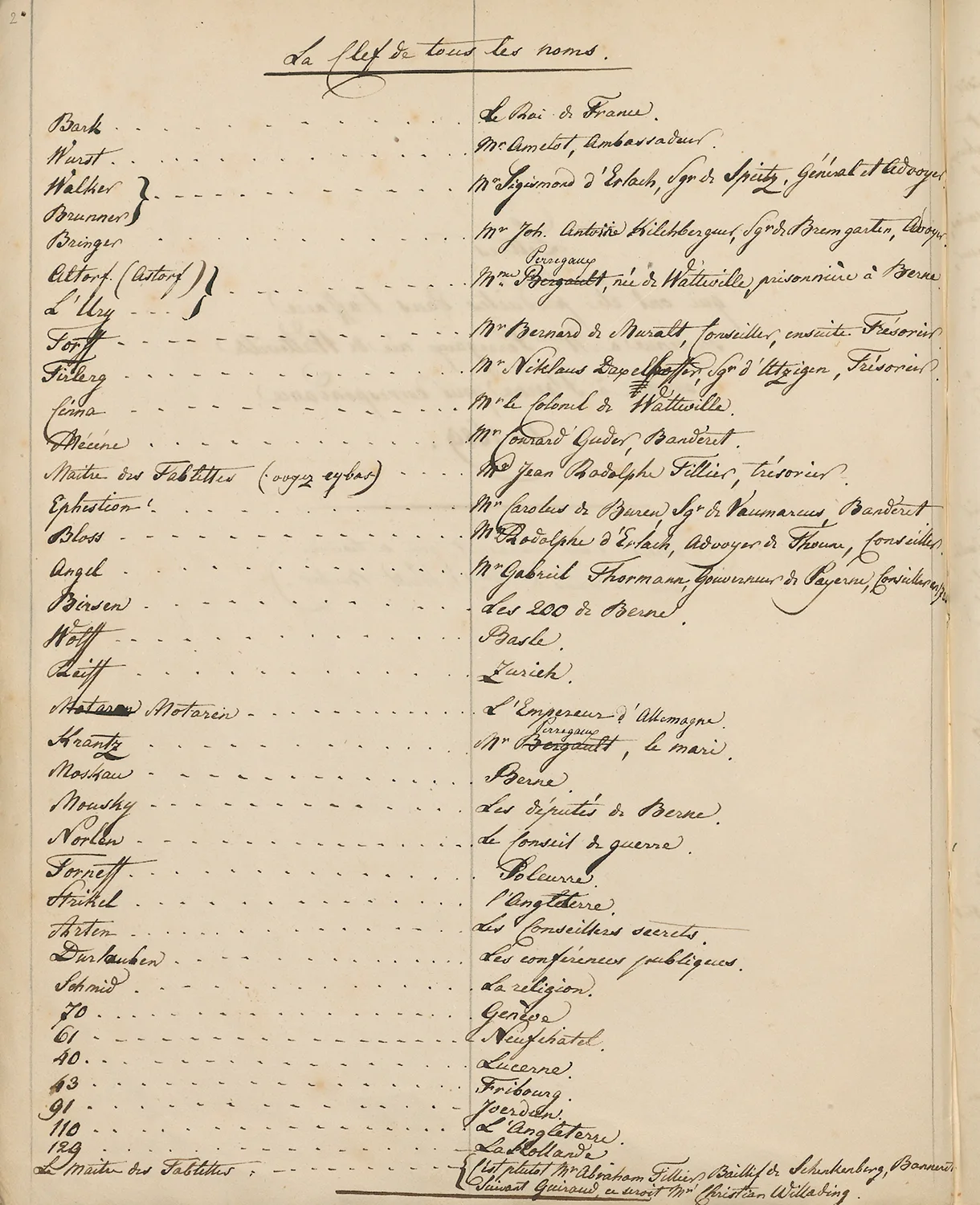

La Sarraz Castle

The Sun King's lady spy

Katharina von Wattenwyl, from Bern, made a name for herself at the end of the 17th century. The price she paid for becoming embroiled in spying for the French court was imprisonment, torture and exile. People are still fascinated to this day by the life and fate of this extraordinary woman.

Katharina Franziska Perregaux von Wattenwyl (1645–1714) was a woman who has managed to earn herself a place in the history of early modern Switzerland. Not because the predominantly male historians of the day regarded the daughter of a Bernese patrician as worthy of mention. No, almost everything that we know about Katharina today is thanks to her own memoirs. She wrote these for the French King Louis XIV shortly before her death, while she was in exile in Valangin Castle (NE). So who was this woman, whose fate has inspired works of art and novels and whom we still find fascinating today?

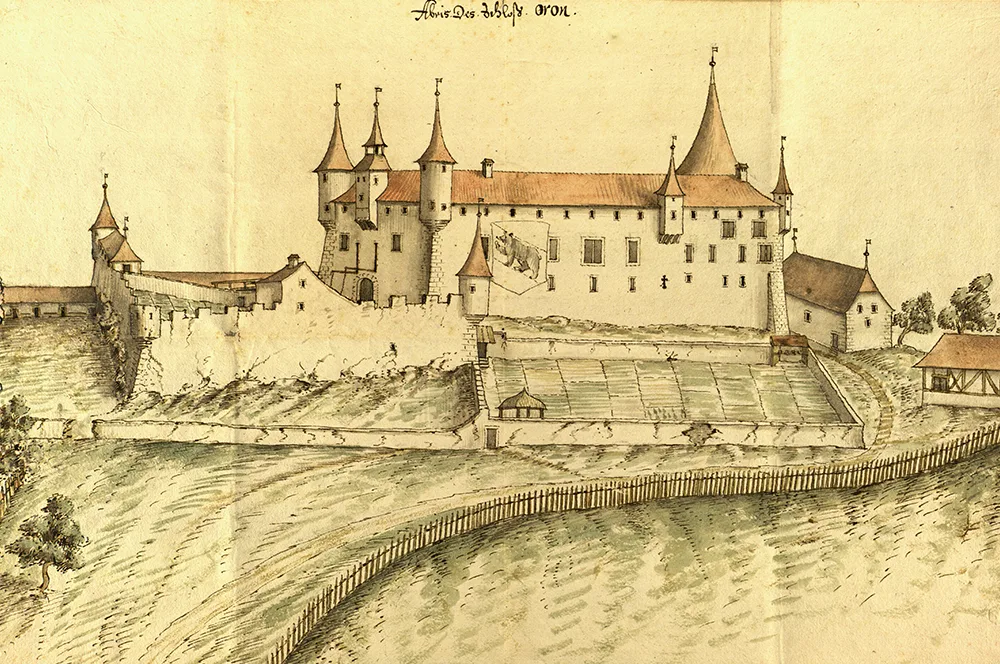

Katharina was the youngest of eleven children. She grew up at Oron Castle in Vaud, where her father was the bailiff. She was orphaned at 13 and from then on lived in the frequently changing care of various relatives. It soon became clear that the strong-willed tomboy was no ordinary girl: Katharina preferred pistols and shooting practice to embroidery or playing with dolls.

Valangin Castle.

Burgerbibliothek Bern

Oron Castle.

Burgerbibliothek Bern

Some of her actions even led Katharina to be compared to the Amazon women of Greek mythology. She learned to ride and proved to have an outstanding talent for it. When she was 20, she got into an argument with a lady at the French court and challenged her to a night-time duel on horseback with pistols. When she found that people who knew what was going on had removed the ammunition from the weapons as a precaution, swords were drawn. Even though a relative broke up the fight, word of the incident soon spread. Even Christina, Queen of Sweden, was impressed by Katharina and wanted the young woman from Bern to be one of her ladies-in-waiting. However, Katharina's family prevented this, because the queen had converted to Catholicism.

Another event that caused waves was when Katharina single-handedly subdued a horse that had been regarded as untameable, and rode it. The owner of the animal was so full of admiration that he gave her a pair of pistols. She very soon made use of those: when a Palatinate count bothered her while hunting in the forest, she unceremoniously shot him in the shoulder.

Katharina was given a similar pair of pistols as a gift. Double-barrel pistols from Zurich with flintlock, made by the gunsmith Felix Werder (1591–1673), in around 1645–1650. Image: Swiss National Museum

Katharina's impetuous behaviour – so unsuitable in a lady of her status – troubled her relatives, who feared for the family honour. They were keen for Katharina, who was also a drain on their finances, to marry quickly. She was not allowed to marry the man of her choice – a von Diesbach from the Fribourg line of the family, as befitted her status – because he was a Catholic. Katharina rejected all the other candidates. Against her will, she was eventually married off beneath her status to a younger man, Abraham Le Clerc, a young pastor at the Church of the Holy Ghost in Bern.

Katharina felt humiliated in the role of self-effacing pastor's wife, bound by strict requirements governing the clothes that she would now have to wear. To escape the sneering gossip of the town, she arranged for her husband to take up the post of pastor in Därstetten in the Simmental valley. It was at that time that she had her portrait painted, with her magnificent hair flowing loose and wearing a suit of armour and ermine fur (see illustration). It was a more than risky undertaking for any woman, let alone a pastor's wife who was supposed to be a role model. Other women at that time would have their portraits painted wearing dark, simple clothing, with their hair tucked primly under a cap, and a prayer book in their hand. The contrast with Katharina's painting could hardly have been greater.

Theodor Dietrich Roos, Katharina Perregaux von Wattenwyl, 1674, on loan at Jegenstorf Castle until 14 October 2018.

La Sarraz Castle

Following the early death of her husband, Katharina married again, this time the court clerk S.P. who had also been widowed. It was another marriage beneath her status, because she had no dowry. At 36, she gave birth to their son Théophil. Along with this, her only child, the "Sun King" Louis XIV now also began to play an important role in Katharina's life. She admired him and ultimately became involved in spying for the French court. How did such a thing happen? The War of the Palatinate Succession (Nine Years' War) and the anti-Huguenot stance of the king had driven many religious refugees to Reformed Bern, and anti-French voices in the Council were increasingly drowning out any pro-French sympathisers. The leaders in Bern held secret talks about a possible alliance with the English king. Since the new French ambassador Jean-Michel Amelot in Solothurn, seat of France's ambassadors, could not obtain the information he needed, he used Katharina as a secret informant. Via a messenger, she sent him information, some of which came directly from the hand of the pro-French mayor of Bern, Sigismund von Erlach.

The "Sun King" Louis XIV (1638–1715), 1701, Hyacinthe Rigaud, Louvre Museum.

Wikimedia

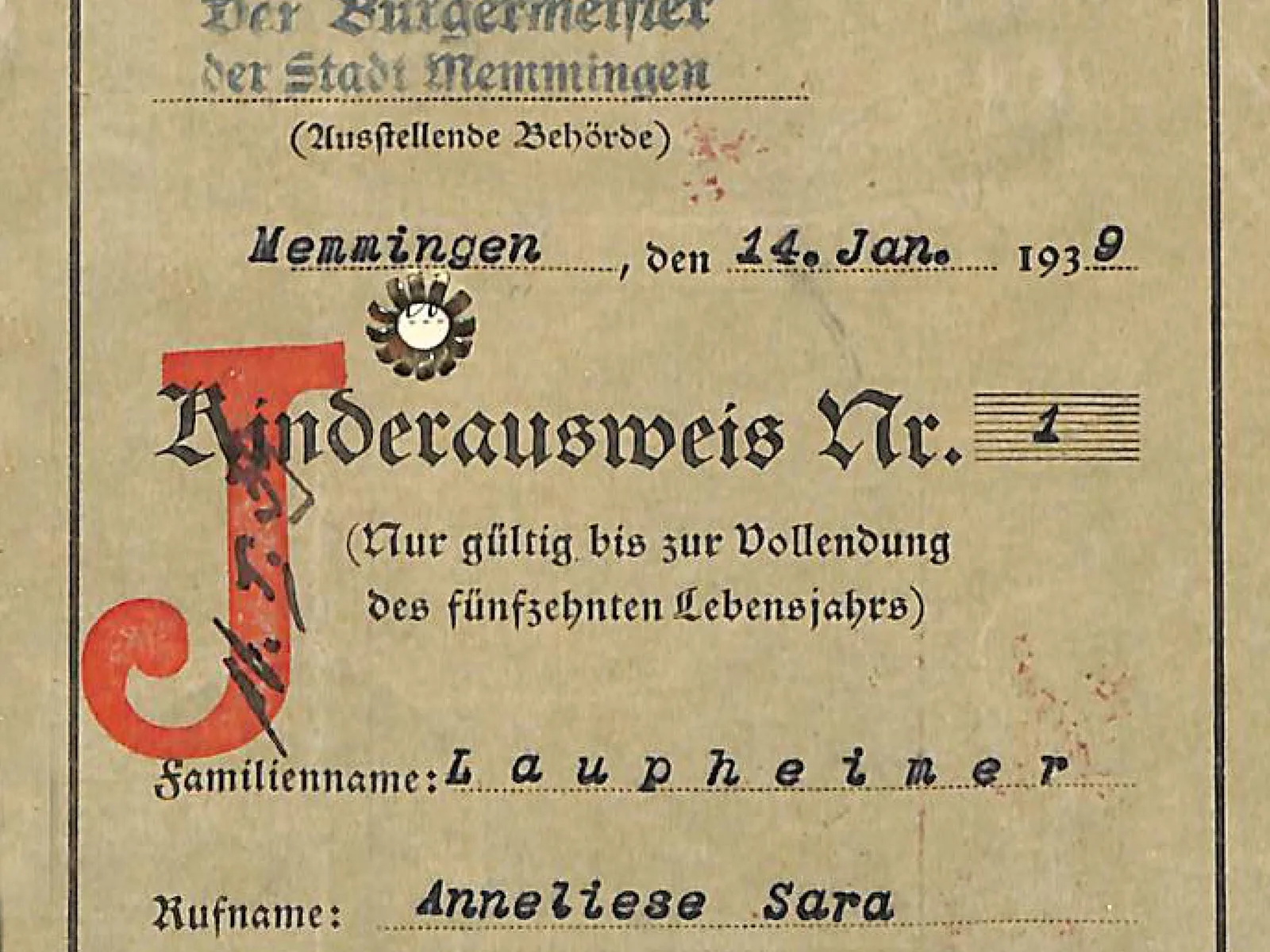

"La Clef de tous les noms" (The key to all names): Extract from Katharina's code-book (copied at a later date) for sending secret information to the French ambassador in Solothurn.

Burgerbibliothek of Berne

Was Katharina acting voluntarily out of political and personal conviction? Or was she hoping to win a position as a pageboy at the French court for her son, who did not have the same career opportunities as a patrician boy, because of his mother's lowly marriage? Or was she even aiming to make a name for herself? We do not know. Anyway, in December 1689 Katharina was exposed when a messenger carrying secret correspondence was intercepted and captured. The Bernese authorities arrested her in the middle of the night and imprisoned her in the Käfigturm tower on a charge of high treason.

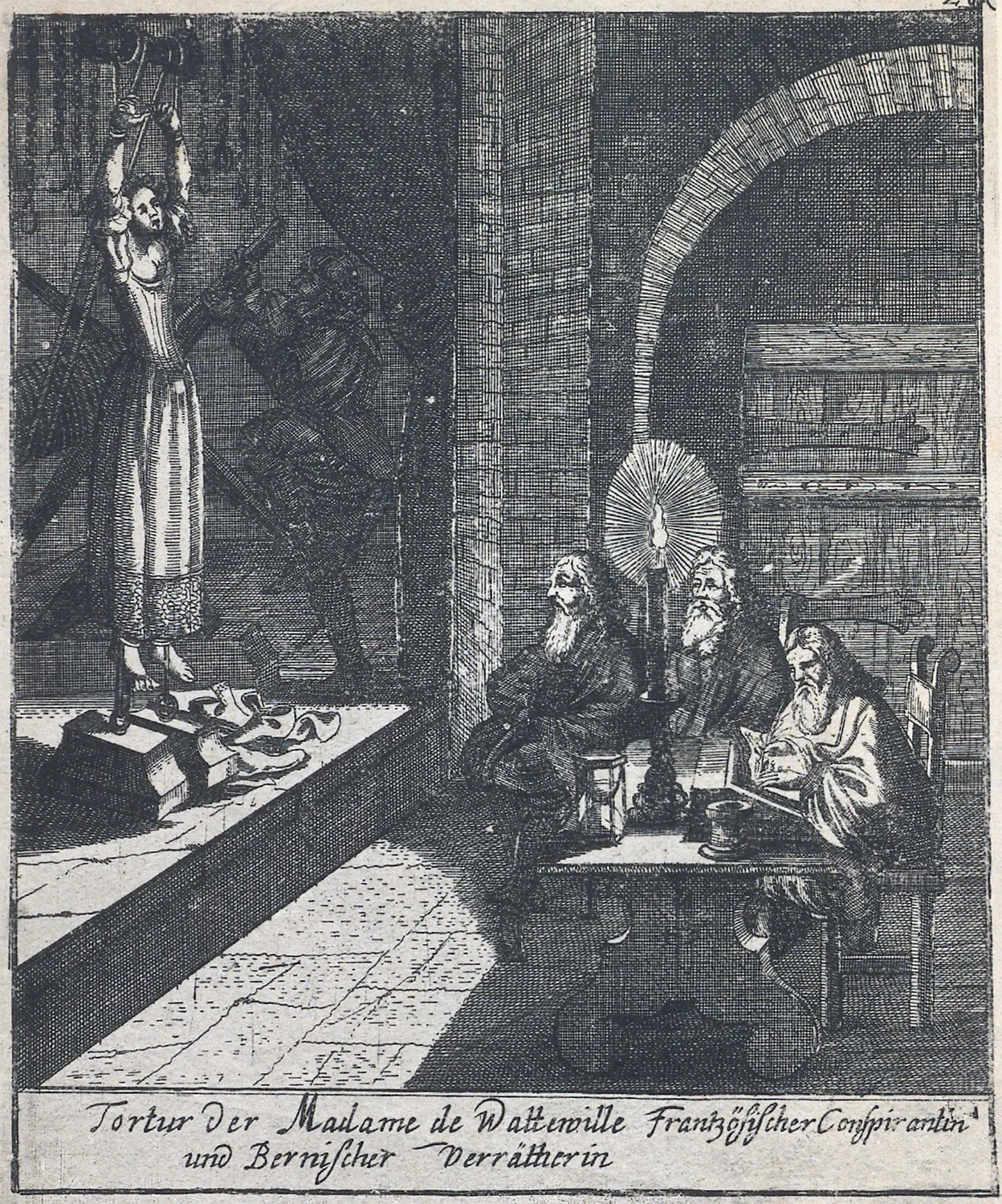

After weeks of interrogation involving cruel torture, the trial ended with Katharina making some confessions, although it is still not clear whether she revealed the whole truth. In any case, it was finally concluded that Katharina had received large sums of money from the French ambassador but that she had mostly invented the information that she passed on. Nevertheless, Katharina was condemned to death. It was only thanks to intervention by her powerful family that the sentence was commuted by the mayor of Bern into a lifelong exile from the territory of Bern, "because they knew that this woman had never been in full possession of her faculties but even from her youth had been believed by everyone to be a crazy fool or half-mad idiot (...)."

It can be assumed that Katharina was a scapegoat in the power struggle between the pro- and anti-French factions in the Bernese government. As a vulnerable woman, she was an easy victim who could be used as an example of how friends of the French were dealt with. Others on that side tried to present Katharina as having acted alone. Her male accomplices escaped scot-free from the whole business, with the true circumstances being hushed up. Most of the court records have been destroyed. However, the French ambassador Amelot did pay the 200 pistoles to settle the court's costs for which Katharina was in fact liable.

Katharina had on her side the founder of the Bernese postal service, Beat Fischer, who is believed to have been a good friend. Shortly after her release, he instructed the well-known Bernese painter Joseph Werner to record the events surrounding the trial in a cycle of allegorical paintings. The ten panels – it is believed there were originally twelve – are today owned by the Jegenstorf Castle Foundation. At the special exhibition "Our women" (see text box), in which Katharina plays a central role, the complex content of the huge paintings, which fill a complete room, can be explored with the help of a new multimedia guide.

The torture of Katharina von Wattenwyl in the Käfigturm in Bern.

Burgerbibliothek Bern

Iron thumbscrew, Oberägeri, 1700–1800.

Swiss National Museum