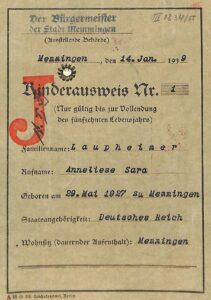

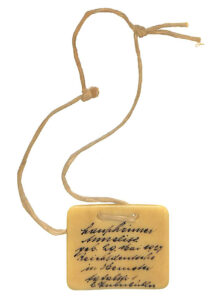

The “300 Children Campaign” of 1939

In 1939, 300 children arrived in Switzerland. The plan was that they would travel on to other countries after a few months. World War II got in the way and many of the children stayed here for years, as Anneliese Laupheimer’s story shows.

Anne Frank and Switzerland

The diary of Anne Frank is world famous. It’s less well known that the journey to global publication began in Switzerland. Anne, her sister and her mother all died in the Holocaust. Otto Frank was the only family member to survive. After the war, he initially returned to Amsterdam. In the 1950s, he moved in with his sister in Basel. From there, he made it his task to share his daughter’s diary with the world whilst preserving her message on humanity and tolerance for the coming generations.