Swiss National Museum

Switzerland’s ‘militia’ system

Even today, Switzerland’s ‘militia’ system of citizen legislature (Milizsystem) is a central tenet of the country’s political culture. But what does the term ‘militia’ actually mean? And how did this system come about?

The term ‘militia’ (Miliz) refers to an organisational principle that is common in public life in Switzerland. Any citizen, male or female, who considers himself or herself capable of doing so can take on public duties and responsibilities on a part-time or voluntary basis. But being part of the citizen legislature involves much more than an additional job or voluntary position as understood in the charitable or non-profit sector. Rather, it refers to a republican identity which – if internalised – is one of the most important mainstays of our Swiss political culture. In that sense, the ‘militia’ principle is still firmly anchored in Switzerland’s political culture and is closely linked to the country’s system of direct democracy.

The term Milizsystem, which is only used in Switzerland, originally comes from the field of warfare (lat. militia). Miliz, usually translated as ‘militia’, is actually the name for a vigilante group, or people’s army, as opposed to the regular army. The term was borrowed in the 17th century from lat. militia, ‘military service; body of the soldiery’, and was initially used primarily in the military sector, and later also for the political sphere.

HISTORICAL ROOTS

The historical origins of the militia principle go back to ancient Greece or, more specifically, to Attic democracy and the early years of the Roman Republic. Even then, the term was used to refer to the exercise of civil office. In the ancient polis, the free and independent, landowning male citizens who were fit for military service met in the People’s Assembly to personally discuss and decide every individual matter. In addition, political offices were usually determined in short-term rotation by the drawing of lots. This was based on the belief that every citizen is obligated and competent to temporarily assume public functions (a system which, with the appropriate political education, would be worth reconsidering today…).

In addition to having their roots in antiquity, ancient Germanic institutions such as the Thing, which are based on old Germanic law, certainly also have their place (He who is honourable is worthy of defending). From the Late Middle Ages onwards, one legacy of these approaches to the concept of a citizen legislature has been the pre-modern collective democracy of the cantonal assembly (Landsgemeindedemokratie) operating in the Swiss Confederation. But clear indications of the militia principle are also found in the federal city cantons.

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) saw, in the old Confederation, the return of the Roman principle of the unity of citizen and soldier, and in his ground-breaking book Il Principe he espouses the principle that a republic such as the Confederation must rely on its own soldiery and not on foreign troops. In respect of the old Swiss Confederation, he therefore stated: ‘The Swiss are well armed and very free’.

The cantonal assembly (Landsgemeinde) is a symbol of the Swiss system of citizen legislature. Here, the cantonal assembly of Glarus, 1941.

Swiss National Museum / ASL

Militia army

In Switzerland, the principle of the people’s army, as opposed to the regular army, goes back to the citizen’s militias that were active in the individual confederate states in the Late Middle Ages. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) had the Swiss federal principle of the people’s army in mind when he wrote in 1772, in his opinion on the complete revision of Poland’s constitution after his return from exile in Switzerland: ‘Tout citoyen doit être soldat par devoir, nul ne doit l’être par métier. Tel fut le système militaire des Romains; tel est aujourd’hui celui des Suisses; tel doit être celui de tout État libre […].’ (‘All citizens should see being a soldier as their duty, not as a profession. Such was the case with the Roman military system; such is the case with the Swiss system today; and such should be the case with any free State […].’) Rousseau thus establishes the positive connection between citizen and soldier, between militia army and liberal state.

Following the model of the French and American revolutionary armies, the first constitution for Switzerland as a whole, the Helvetic Constitution of 1798, laid down the militia principle in Article 25, inter alia: ‘Every citizen is a born soldier of the Fatherland’. From 1830 onwards, the reframed cantonal constitutions then also adopted this principle. The Federal Constitutions of 1848 and 1874 approved compulsory military service (conscription) and prohibited the federal government from maintaining a standing army. It wasn’t until 1999 that the military Milizsystem was explicitly enshrined in the Federal Constitution, under Article 58: ‘Switzerland shall have armed forces. In principle, the armed forces shall be organised as a militia.’ Incidentally, this mention in the Constitution is the only reference to the ‘militia’ principle. The political ‘militia’ principle is thus to a large extent part of the unwritten constitutional tradition. That is likely why it has so far been given scant attention in the constitutional and historical research and literature on the old Swiss Confederation and modern Switzerland.

THE CITIZEN LEGISLATURE SYSTEM IN POLITICS

Since antiquity, there has been evidence that the militia system has also been carried over to the political sphere. From the 13th or 14th century onwards, the federal towns and cantonal assemblies already mentioned have implanted the militia concept in their populations; see, for example, the Federal Charter (Bundesbrief) of 1291, and other founding documents of the Swiss Confederation. The political roots of the militia system are therefore firmly planted in the Ancien Régime. The principle of voluntary, non-paid action has left its mark on scores of cooperative forms of organisation on the territory of present-day Switzerland. The collective relied on the ‘most able’, on their willingness to sacrifice their time and resources for the community. No doubt the Christian principle of caritas – that is, the duty to provide assistance to the sick, the handicapped, the poor and the destitute – was also at work, as reflected in an array of charitable voluntary organisations such as the Samaritans.

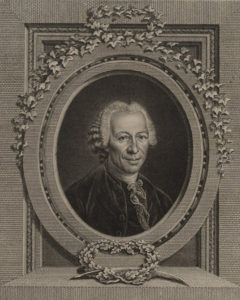

Beat Ludwig von Muralt (1665-1749), an Early Enlightenment philosopher from Bern, and the Basel Enlightenment philosopher Isaac Iselin (1728-1782) called for Switzerland to create a republican identity of its own. Within this framework they emphasised the concept of the militia and the principle of mutual interest, laying the foundations, with their philosophical writings, for a discussion of virtue. Republican values such as courage, thrift, mutual aid, trust in one’s own judgement and contempt for courtly grandeur were necessary in order to establish a national self-image and a Swiss communal republic. Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746-1827) and Philipp Albert Stapfer (1766-1840) then developed these ideas further, creating connections between the modern republicanism based on the idea of the militia, and Switzerland’s early liberalism.

Graphic print with a portrait of Isaac Iselin, about 1780.

Swiss National Museum

The reframed cantonal constitutions from 1830 onwards then explicitly carried over the militia system to the municipalities and their system of self-government. In all public affairs, citizens were required to shoulder their share of responsibility for the local community. This was the basis on which the republican form of government was founded, and from which it continues to draw its vitality. It was therefore common for the key positions in government to be occupied for the term of office not by salaried municipal authorities or civil servants, but by ordinary citizens.

Together with the associations and societies which took hold in the 19th century, in political terms the ‘militia’ principle is still a fundamental characteristic of our federalist, populist nation, at municipal, cantonal and federal level.