Keystone Keystone

The cheese collective

From 1914, the Schweizerische Käseunion (SKU, the Swiss Cheese Union) ensured people at home and abroad were kept supplied with Swiss cheese. For that purpose, the Cheese Union monitored both production and prices.

The Genossenschaft Schweizerischer Käseexportfirmen (Association of Swiss Cheese Export Firms), better known as the Cheese Union (SKU), was established in late summer 1914, at the urging of the federal authorities. The members of the Cheese Union were the organised cheese exporters, milk producers and cheesemakers, and the consumers banded together into the Verband Schweizerischer Konsumvereine (VSK, the Federation of Swiss Consumer Cooperatives – now Coop). The purpose of the monopoly was to secure the supply of cheese for the country’s population, and to organise cheese exports. The revenues from the export of hard cheese were used to cover the additional costs incurred in the production of milk due to the price increase caused by the war. This made it possible to keep the price consumers had to pay for fresh milk well below the global market price.

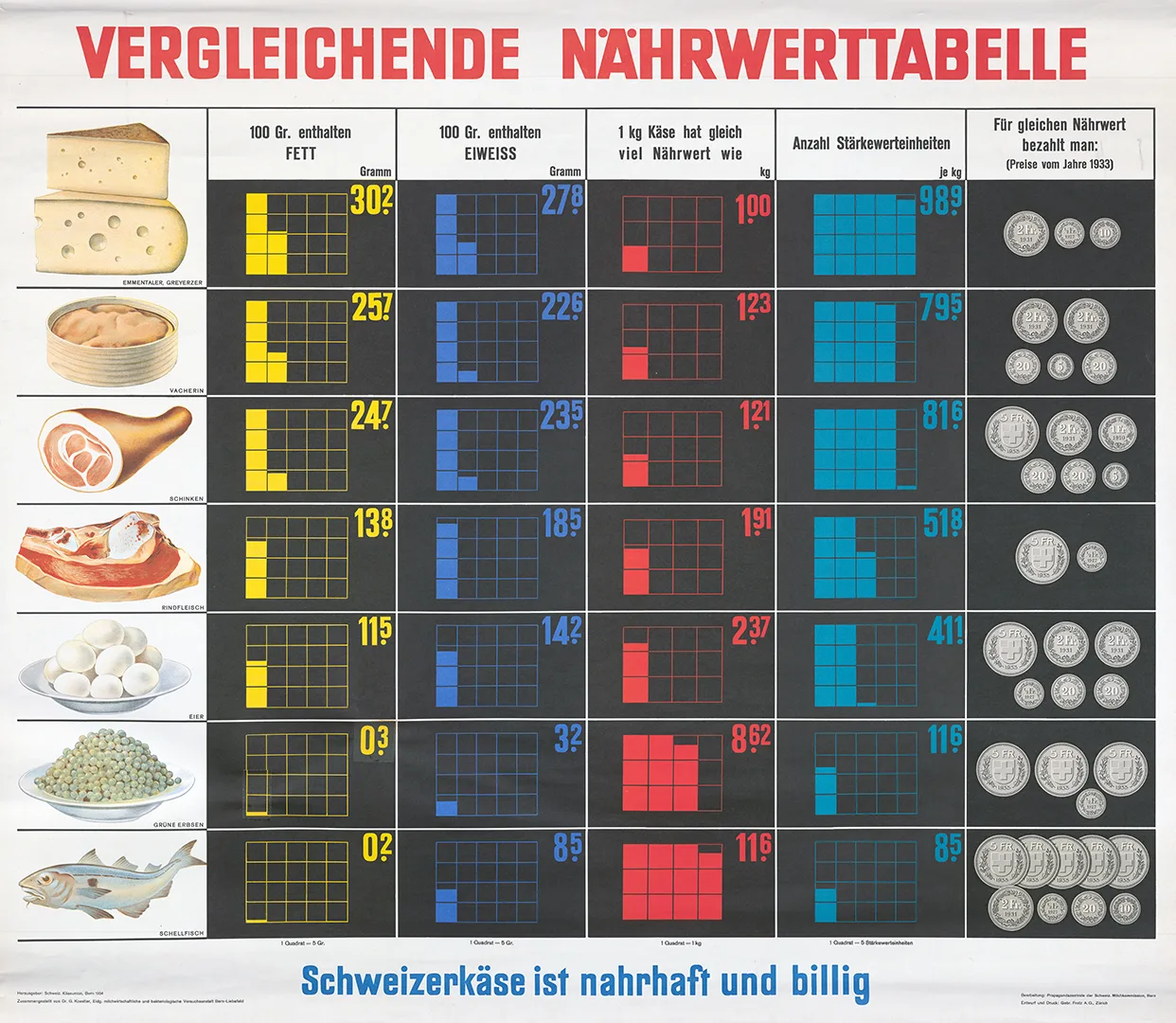

Table of nutritional content produced by the Swiss Cheese Union, 1934.

Swiss National Museum

The fact that milk producers, buyers and cheese exporters were able to arrive at a joint approach so rapidly after the outbreak of the war was quite a feat. Just a short time previously, they had been embroiled in what were known as the ‘Milk Wars’. The conflicts had erupted because milk producers insisted, at the beginning of the 20th century, on making the price of milk an object of negotiation. In the 19th century, the price that farmers received for the milk produced by their cows had been determined by events outside the country. Generally, it was one twelfth of the price the exporters obtained for the hard cheese overseas. Many farmers found it neither right nor fair that that price should automatically also apply for the milk consumed in Switzerland as fresh milk. Just as the workers had begun to open up the discussion, via their unions, of the value of the work they did, so the farmers now wanted to negotiate the value of their milk. To strengthen their position vis-à-vis the milk buyers and cheese exporters, they formed regional and national associations. These associations were able to get hold of figures and knowledge about the price formation mechanisms, enabling them to negotiate on an equal footing with the exporters and milk buyers. While the debates about the ‘correct’ price of milk culminated in the conflicts that were known at the time as ‘Milk Wars’, those involved learned not only how to fight a battle, but also how to cooperate, negotiate prices and make compromises. These proved important foundations for the creation of an organised dairy market, which ensured after 1914 that cheese could be exported at a profit, and at the same time was available throughout Switzerland under the same terms. From 1914 until its dissolution in 1999, the Cheese Union embodied this policy on more than just a symbolic level.

Cheese production, around 1926.

Swiss National Museum

First World War cheese ration stamp, around 1914-1919.

Swiss National Museum

While securing domestic supply was at the core of the Cheese Union’s activities during the First World War, in the inter-war period the organisation’s work increasingly focused on promoting cheese exports. After the Second World War it continued to develop this activity, presenting Emmental, Gruyère and Sbrinz at trade fairs, cookery classes and other events virtually the world over. It had its own advertising agencies in many countries.

At home, too, the Cheese Union sought to promote cheese sales. For example, it created new ‘branded products’ such as fondue and processed cheese (Schmelzkäse). The latter was originally developed for export to the tropics, and sometimes made up a fifth of total exports. But it was also relatively popular in Switzerland in the post-war period. In addition the Cheese Union, together with the dairy associations, from time to time obligated the milk producers to buy back as dairy products a percentage of the milk they supplied to the dairies. In particular, the Schmelzkäse processed cheese, popularly known as ‘Blockkäse’, which was sometimes difficult to sell, had to be ‘bought back’ by milk suppliers. However, this form of ‘forced consumption’ probably caused a drop in cheese consumption in the long run: in the 1950s and 1960s, whole generations of farmers’ children grew up (mis)believing that the good milk, in the production of which they were usually directly involved, would mostly be made into Blockkäse. Although this type of cheese did of course have its devotees here and there, on the whole it was quite an unappealing culinary example of what industrial manufacturing processes could make of milk as a ‘natural processed product’.

The Cheese Union as an organisation was broadly supported, but its operations were nevertheless always contentious. In the wake of the neoliberal ideas of social order which took hold during the 1980s and 1990s, the Cheese Union came to be regarded principally as a ‘cautionary tale of abuse of power and fondue’. More recently, however, transnationally oriented historical research has painted a more nuanced picture that also includes the nutritional and socio-political achievements, and the sometimes innovative marketing strategies of the Cheese Union.

The Cheese Union was also responsible for this: the Swiss national team’s ski suit from 1992 to 1998.

Keystone