Sport as a class struggle

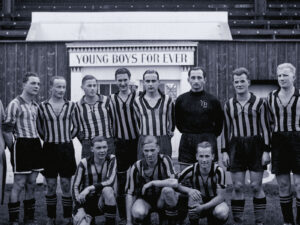

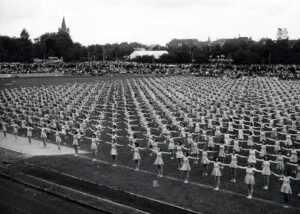

“Sport” as a one-size-fits-all concept has never existed; it is too heavily influenced by societal factors and social milieu. For example, there used to be a strong sports movement for workers.

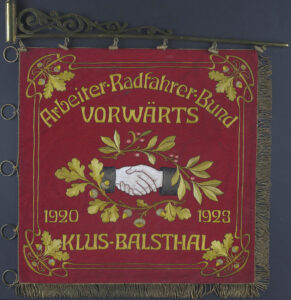

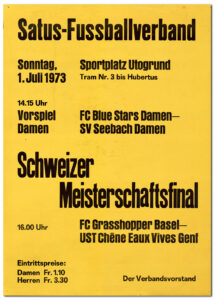

Working class sport and “bourgeois” sport as a sign of social division

Between proletarian internationalism and spiritual defence (Geistige Landesverteidigung)

Loss of relevance in the economic upturn

Swiss Sports History

This text was produced in collaboration with Swiss Sports History, the portal for the history of sports in Switzerland. The portal focuses on education in schools and information for the media, researchers and the general public. Find out more at sportshistory.ch