Museum tours for armchair travellers

Our beady-eyed Museum owl, Hibou Pèlerin, really has no time at all for flight shaming. But at this time of year, her desire for travel and adventure does slow down a bit. So, she took a little surfing trip into the realm of online exhibitions.

Just a few years ago, you were lucky if the websites of most museums could be relied upon to provide the most important information. Now, however, we’re seeing a veritable explosion of online content to help people prepare for their museum visit, and relive the experience afterwards. In some cases, this content is even presented as a viable alternative to the real thing.

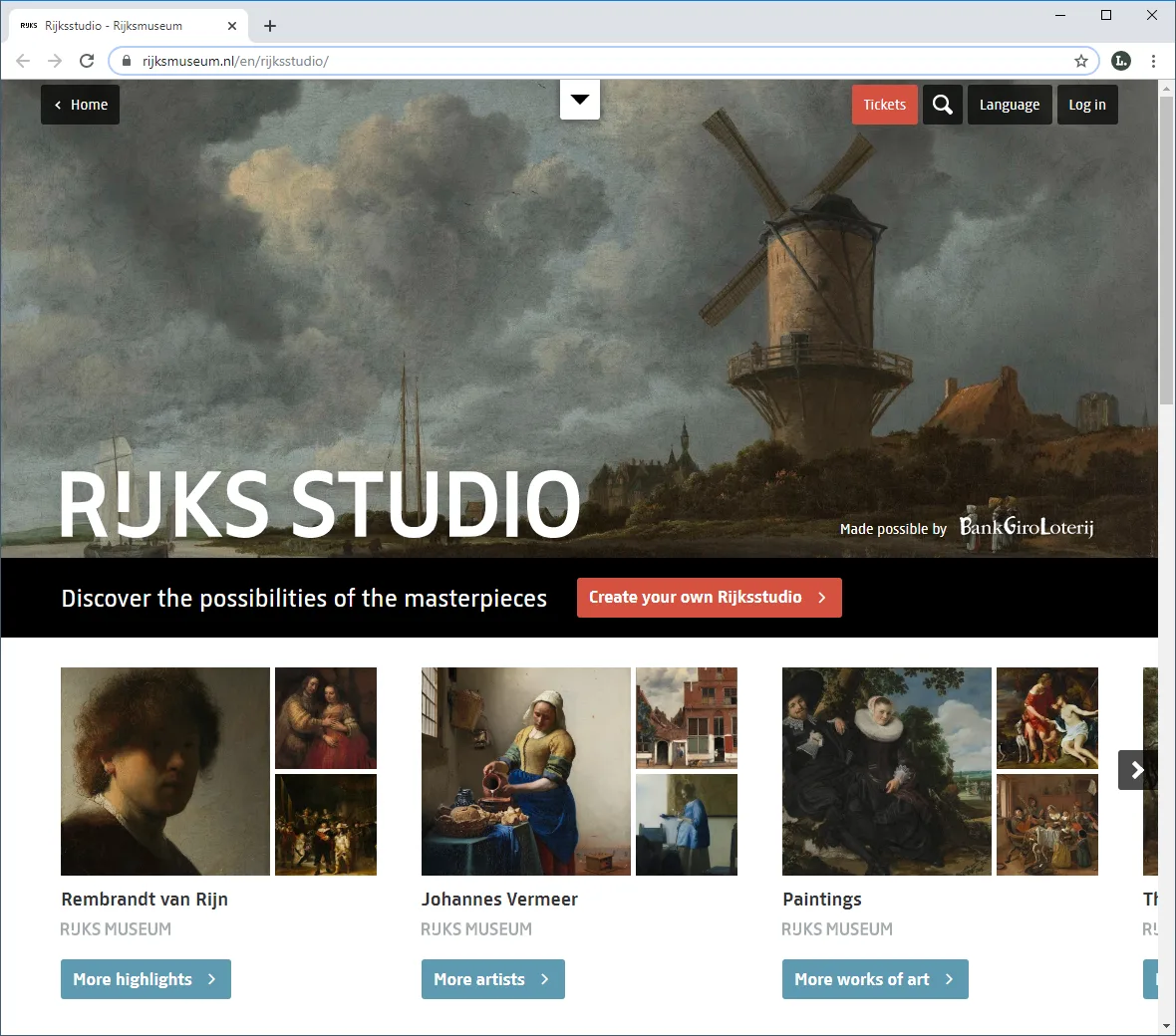

Rijksmuseum

Some of this online content, such as the ‘Rijksstudio’ project by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, has attracted a lot of attention. The Museum has been putting its non-copyright collections online since 2015. Anyone can download the image files for non-commercial purposes; the Museum even provides the tools for digital editing. Visitors have now created a number of virtual tours through the Museum’s holdings, based on the online collection. Are you looking for exhibition material about tulips, Art Nouveau, or even the colour brown? Nothing is impossible. But the enthusiastic public response to this online push by the Rijksmuseum has also revealed its limitations. With just under 700,000 works of art and almost half a million individual ‘studios’ that now need to be examined, the question arises: how do you sort the wheat from the chaff? The best thing is to dip in and have a little taster. And that will probably achieve the campaign’s main goal: you’ll be looking forward to your next visit to the Rijksmuseum, to see the originals.

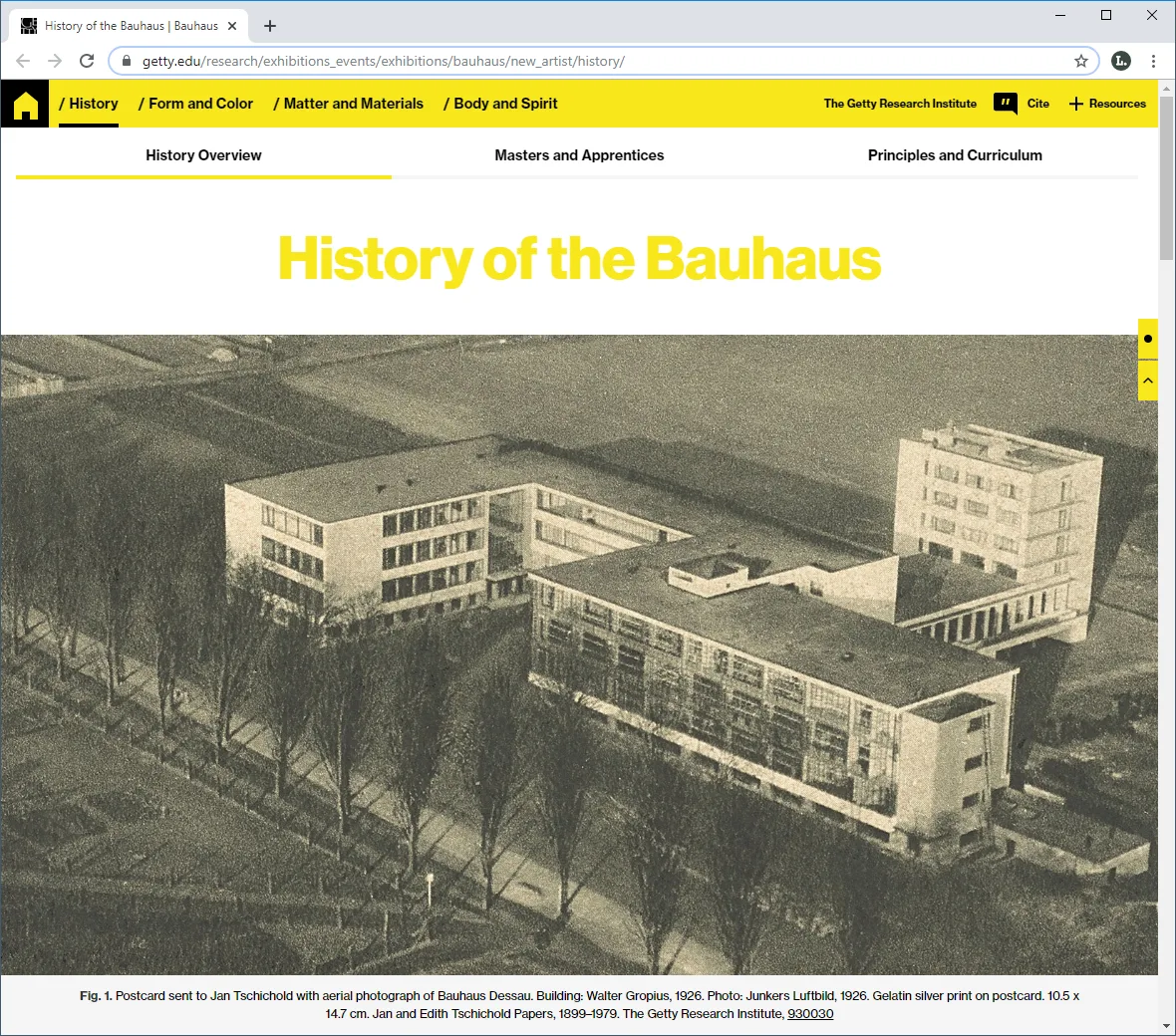

Online Collections

Putting the collection online, at least in part, is gradually becoming standard practice. Leading the charge in this regard are institutions such as the British Museum, with an online database comprising four million objects. The current trend is for ‘online exhibitions’, which either complement an actual exhibition currently being held or are stand-alone, i.e. independent of other exhibitions. For instance, one of the world’s leading art institutions, the Getty in Los Angeles, is hosting a virtual Bauhaus exhibition, entitled ‘Bauhaus – Building the new artist’. The exhibition only exists online, but is based on documents that are also on display in the museum. It has succeeded because it fully exploits the possibilities of the medium, with a mix of video, sound and animation. You can watch a new production of Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet, and a tutorial invites visitors to reproduce the design exercises of Josef Albers. This online show works because it doesn’t succumb to the temptation to indulge in a battle of digital materials, but instead remains focused on the subject at hand.

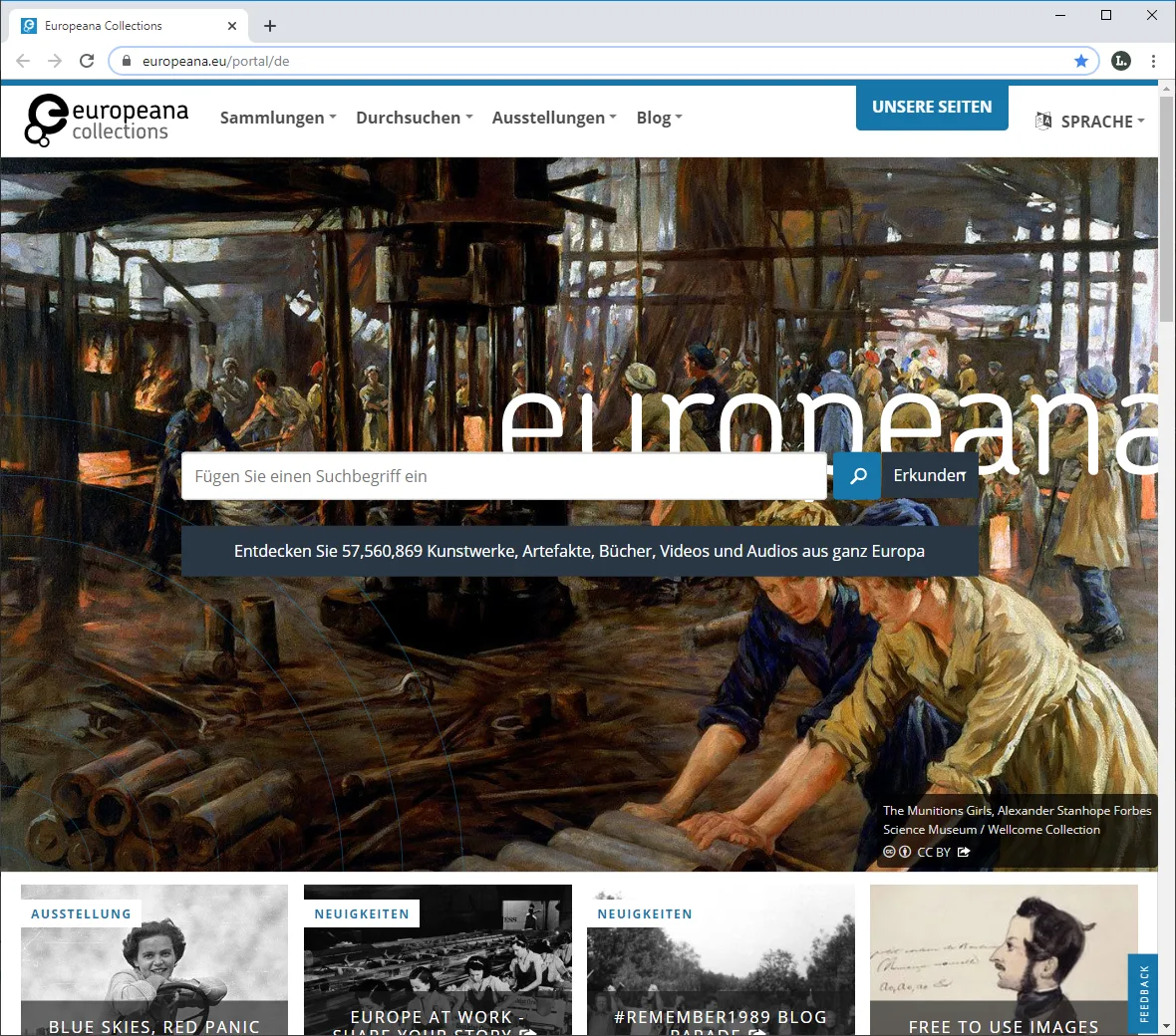

Europeana

The European digital platform Europeana, a European Union project which is still relatively unknown among the general public, is a veritable treasure trove of exhibitions that are only offered online. The platform brings together on a single site a large number of public archives from across Europe. The main focus is on photographs, art, historical documents such as old maps, and ethnographic musical recordings. Visitors to the platform can select specific sections, enter key words or browse the documentation and blogs compiled by an editorial team. Those using the site will stumble across scores of original and unexpected surprises. Quirky material such as ‘Liberation skirts’, home-made skirts ingeniously put together out of fabric scraps after the Second World War, or photographs of historic neon signs. There are also contributions relating to more current issues, such as a piece on the subject of restoration in the wake of the Notre-Dame fire. The archive is more than just a pool of resources provided by numerous European institutions – it’s also designed for participation. At present, for example, members of the public can upload their images of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Iron Curtain. Europeana also has a political dimension in terms of internet usage. It is a statement in support of public, non-commercially oriented online content.

Smithsonian Institution

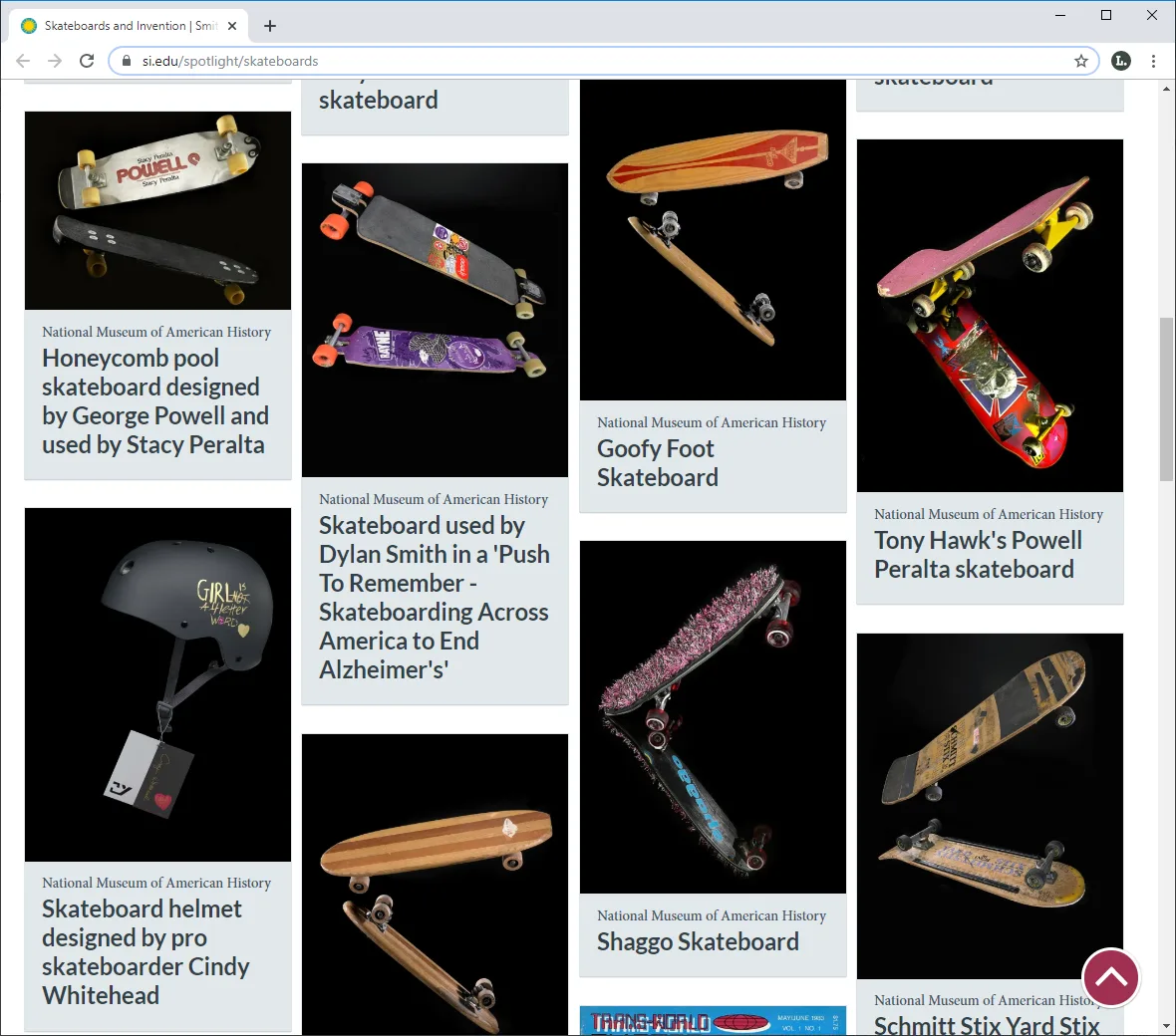

When surfing all this content, it very quickly becomes clear that larger, well-funded museums are able to have a more lavish online presence. This is particularly true in the United States – for example, at the venerable Smithsonian Institution in Washington, which brings together under a single umbrella several museums of natural and cultural history. Like Europeana, the Smithsonian offers a plethora of themed online exhibitions, likewise on subjects to pique the curiosity. ‘Skateboards and invention’ explores skate culture’s creative spirit and history of innovation, with commentary on examples from the Smithsonian’s various collections. Another story highlights the role of the accordion as an instrument commonly used among migrants.

MET and MOMA

Another treasure trove is the website of the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The site offers not only more than a thousand online stories, but also a whole array of specific online content, such as #MetKids for children. The ‘Digital Timeline’, now famous among experts, gives access to the complete Museum holdings in chronological order.

Even the individual museum history is discussed here and there. This is where the recently refurbished Museum of Modern Art in New York, which has now placed on the web photographs and documents relating to the five thousand or so exhibitions held since the Museum opened in 1929, delivers a brilliant performance. Naturally, the Museum is also underlining its not unproblematic claim to wielding interpretive authority in the field of art and design.

There are other examples that are relatively easy to find – some of which show that a new business model is apparently evolving. This includes the global, and not entirely uncontroversial, Google Arts & Culture project. Instagram, by contrast, is still more of an experimental corner for image blogs of every kind, including those of artists such as Cindy Sherman (@cindysherman) and photographers such as Martin Parr (@martinparrstudio) and Stephen Shore (@stephen.shore). But at this juncture we will leave the actual terra firma of the museum and arrive, finally, at the crucial question for the museum folk: how do we get the upcoming generation of ‘digital natives’, those who are permanently attached to their devices, into museums in the future? One thing is now clear, and that is that without well-made digital content, that’s unlikely ever to happen. And well-made means that, ultimately, the content will result in the user being seduced, sooner or later, into seeking out an encounter with the real objects in an actual museum.

PS: We were extremely delighted, on our surfing tour, to make the acquaintance of the long-time Museum owls of the Smithsonian. True to the mission statement of the Institution’s founder, which envisaged increasing and diffusing knowledge, the owls are named ‘Increase’ and ‘Diffusion’. We couldn’t agree more.