wikimedia/Autopilot

Back to the early days of computer gaming with text adventures

In the early days of the computer, there were games that were based entirely on text. Although they were soon replaced by graphics-based games, this genre is central to understanding the history of the computer, and the games still have their fans today.

Larry Laffer is anything but a role model: he spends most of his time in dimly lit bars indulging in alcohol and cigarettes, always on the lookout for the great love of his life who, of course, he’s never going to find like that. Well, even if he’s no role model, he’s still something of a likeable loser…

Larry isn’t an actual person, of course – he’s the main character in an early computer game called Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards. In this game, players had to guide Larry through the local night life. At that time, they had only simple language commands in English at their disposal. The game, which was popular in the 1980s, featured primitive graphics. If you wanted to make progress in Leisure Suit Larry, you needed patience and intuition, as the writer had to experience for himself. The developers may have anticipated that, because the computer also responded to expletives, writing back ‘Don’t swear like a bloody sailor’!

Notwithstanding its simple graphics, Leisure Suit Larry was, in essence, a game based entirely on language. So Larry’s antics are also referred to as ‘text adventures’. The game emerged with the first home computers in the 1980s – the Commodore 64, the Atari and other machines. It was further refined later on, and can still be played in a modern version today.

Screenshots from an early version of the game Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards which, despite featuring some rudimentary graphics, was essentially a text adventure. The game can be played free online at archive.org.

classicgaming.cc

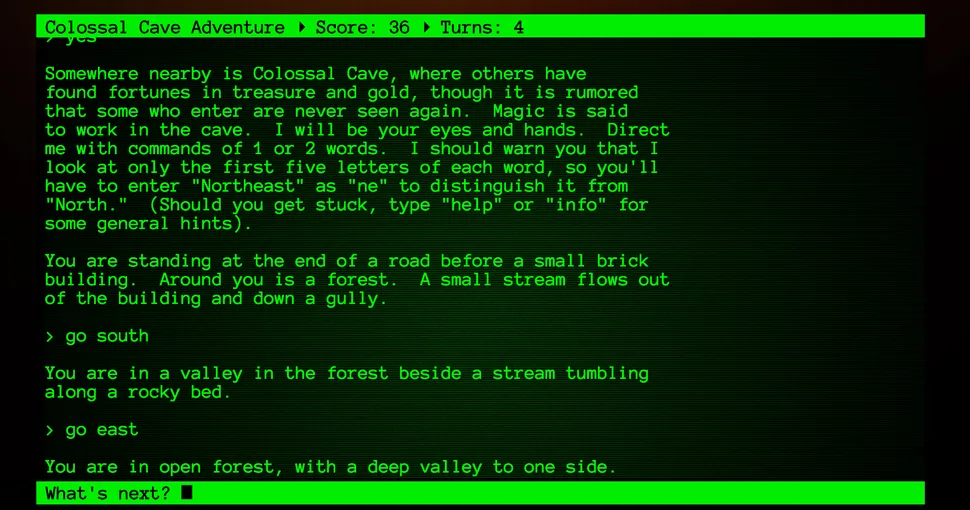

But it wasn’t the first text adventure. This genre was invented back in the 1970s. The first such game was created in 1975, and is attributed to the authors Will Crowther and Don Woods. It was played on a PDP-10 mainframe computer from DEC – a large cabinet – and to begin with was thus an exclusive treat for computer specialists. The player had to navigate through a gigantic cave system. The developers gave the game a variety of names, finally calling it Colossal Cave Adventure. Other computer specialists built on this game idea, and developed the game Zork. Zork starts in a wooden hut and also goes underground, where the player’s objective is to find 20 precious objects. After completing their studies, the developers sold a commercial version in the late 1970s.

Screenshot from the game Colossal Cave Adventure. It is considered the first text adventure. The classic version can be played free online at amctv.com.

These games only had a short life, especially since their reach was limited due to the lack of availability of computers. But they laid the groundwork for future developments. In the early days of home computers, these games were soon obsolete – the market wanted pictures, and the fast pace of development in the computing world got better at meeting this demand year after year.

But text adventures are not forgotten; they live on in their own little niche. This type of game has attracted renewed attention recently due to the keen interest in artificial intelligence (AI). The core of the game software is what is known as a parser, which translates human language into computer commands, and such parsers are also required for AI.

Text adventures have established a new genre: interactive fiction. This refers to stories which engage in dialogue with the reader and always offer a range of different options, determining the flow and outcome of the story. Traditional storytelling thus takes on a new dimension – the task of telling the story is in part suddenly handed over to the computer user who is reading (or playing?). Traditional literary studies are also becoming increasingly interested in how these new scenarios work. In his PhD project in the German Department at the University of Zurich, specialist in German studies Bojan Peric explores the question of the literary quality of digital interactive stories. The genre is still practised today, and requires from its audience a willingness to do a lot of reading and to play through possible narrative alternatives.

This may also be related to the fact that programming such games has become literally child’s play, and is in principle carried out by software that can be installed free of charge. This allows developers to concentrate fully on the language level. Twine is one of the more popular programmes, with a dedicated fan base having become established around this software. Even serious issues can be dealt with, as demonstrated by Zoë Quinn’s game Depression Quest, which caused great controversy back in 2013. The game depicts the world of a depressive person, and aims to foster greater understanding of this illness. It was widely praised by the general consumer press, but received a critical reception from the actual gamer crowd. Like hundreds of other text adventures, it’s easy to find and play today. Text adventures have thus landed virtually unchanged in the present day.