Swiss National Museum / ASL

Masterstroke on the Matterhorn

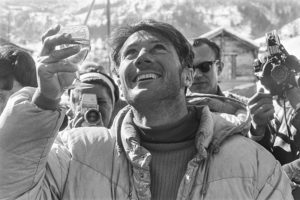

There was a time before mobile phones, a time when press photographers were the eyes of an entire nation. Many of the images they captured are now forgotten. For example, the enraptured photo of Walter Bonatti after his first solo traverse, in winter, of the north face of the Matterhorn.

It’s as if they can’t believe their eyes. Is it him? Is Walter Bonatti really here, back in the valley? The scrutiny puts him in the centre of the action. A colour photograph would show his cap red, his ski goggles yellow, and his jacket – his hallmark – blue. The black and white image, however, depicts a shining presence in the midst of people in dark clothing. On the left and right, wavy hair, fur collars, a necktie, catch the eye. The background is dominated by the mountain massif with the two huts; the sunlight, only just captured at top right, is fading.

The man in the centre has just made history. Not for the first time. The talented and successful Italian mountain climber was famous for numerous first ascents and new routes. In 1954 Walter Bonatti was part of the first ascent of K2, the supreme achievement of Italian alpinism. A scandalous falling-out within the expedition team robbed him of the glory of reaching the summit. Deeply disillusioned and frustrated, he chose after that to climb solo most of the time. That was what was so special about his latest coup. 100 years after the first ascent of the Matterhorn by a seven-man roped party led by Edward Whymper, he conquered the mountain’s north face in 1965 by a new route – in winter and, to cap it off, alone.

Welcome for Walter Bonatti on 23 February 1965 in Cervinia, on the Italian side of the Matterhorn.

Swiss National Museum / ASL

For this brief photographic moment at least, the impression is created that Bonatti would have been more comfortable with the solitude of the mountains than fighting his way through the adoring crowd. His arms are slightly drawn in, shunning contact. Facial expression and posture contrast with the intrinsically dynamic image of the hero, who is trying to move forward, directly towards the viewer. This antagonism between momentum and restraint creates an intriguing abstraction. If you look at the image for long enough, you might even think for a moment that Bonatti is running backwards, as in a film that’s being rewound.

Perhaps, at that moment, Bonatti’s mind was running through not only the several days he’d spent climbing to the Matterhorn summit, but his entire career. His return from the Swiss landmark also marked his retirement from the sport. From extreme mountaineering, at any rate. He then moved into the profession of those he seems here to be reluctant to be around: he became a photojournalist. And author. In his second career, he was interested in sharing his experiences and emotions. For him, the confrontation with nature – the mountain – was synonymous with developing his moral character. This, incidentally, was what his contemporaries always emphasised: Walter Bonatti was kind, calm and courageous.

The press photo agency ASL

Actualités Suisses Lausanne (ASL) was founded by Roland Schlaefli in 1954, and until its closure in 1999 was the leading press photo agency in western Switzerland. In 1973, Schlaefli also took over the archive of Agentur Presse Diffusion Lausanne (PDL), founded in 1937. The holdings of the two agencies comprise approximately six million images (negatives, prints, slides). In the broad range of subjects covered, there is a focus on federal politics, sport and western Switzerland. The agency opted not to take the step into the digital age. Since 2007, the archives of ASL and PDL have been held by the Swiss National Museum. The blog presents, in a loose chronology, images and photo sequences that particularly stood out when the collections were being recatalogued.

A toast to the mountain – a climber’s friend and adversary at the same time. The Bonatti route across the north face of the Matterhorn has been reclimbed only three times to date – by Swiss alpinist Ueli Steck in 2006, for example.

Swiss National Museum / ASL