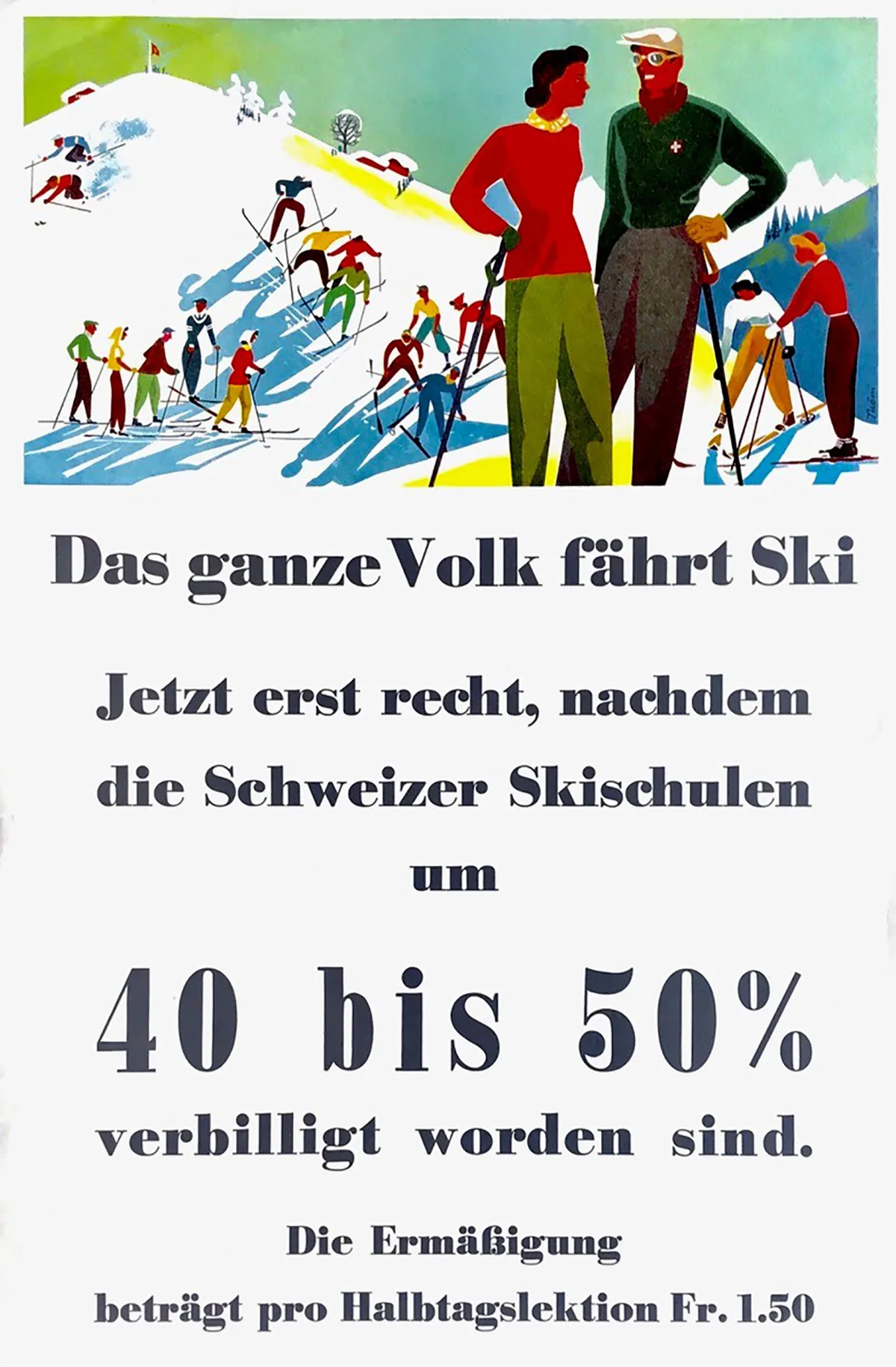

The whole country is skiing! The whole country…?

Switzerland sees itself as a great skiing nation. Where does that self-image come from? Is it more of a myth, or more of a reality?

Vico Torriani’s song made Switzerland see itself as a nation of skiers. YouTube

Alpine skiing is a British invention

Wars make skiing more of a domestic affair

Pirmin Zurbriggen wins Super-G in Schladming, 1988. YouTube

Swiss Sports History

This text was produced in collaboration with Swiss Sports History, the portal for the history of sports in Switzerland. The portal focuses on education in schools and information for the media, researchers and the general public. Find out more at sportshistory.ch