ETH Library Zurich ETH-Bibliothek Zürich

Serious crashes

The 1920s were the decade of aviation. Air shows expressed visions of hope and expansion. But because of one fatal accident, aviation in Switzerland took a different direction, moving away from spectacle towards civil aviation. This change of direction happened exactly 100 years ago.

It was Whit Monday 1920: the weather was fine, and the big air display in Romanshorn attracted thousands of flying enthusiasts. The pilots of the company Ad Astra took paying passengers up for short demonstration flights and then, at 2 p.m., the programme featured daring aerial acrobatics. From accounts coming out of World War I, the spectators knew of the daredevil manoeuvres the pilots were capable of performing with their flying machines.

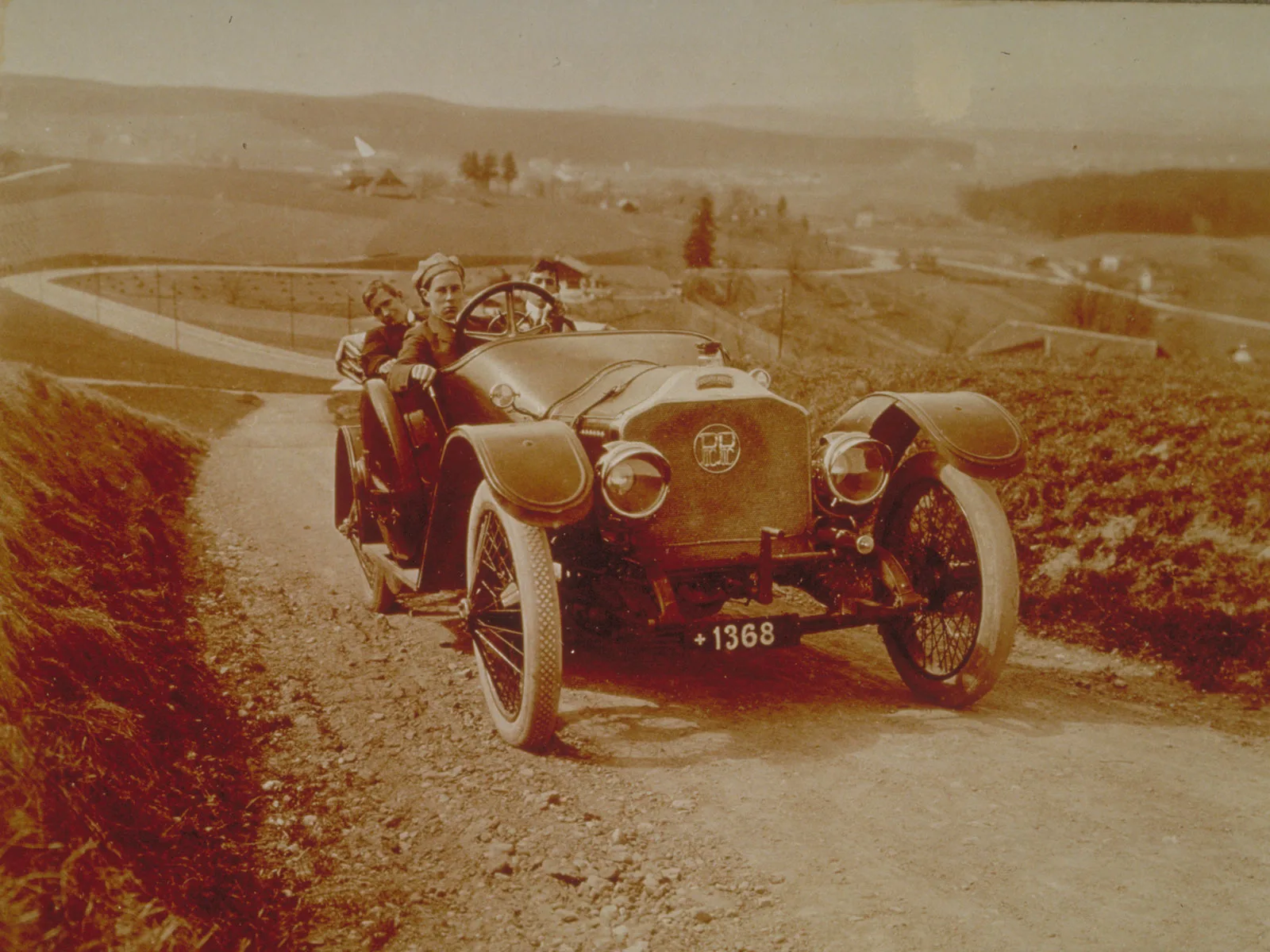

Flight Lieutenant Emile Taddeoli, the second Swiss person to gain his pilot’s licence and, at 41, an experienced flyer, started up his Savoia biplane; his mechanic, 23-year-old head technician Yvo Giovanelli from Milan aircraft engine factory Isotta Fraschini, climbed aboard. People knew about Taddeoli, a Ticino native now living in Geneva, because he had been flying since 1909 and had dazzled audiences with his airborne artistry at numerous air shows, and because he was also active as an automobile racing driver, but also raced motorbikes and bicycles.

Ernst Frick, Emile Taddeoli and Alfred Comte pose in front of a Savoia, ca. 1920.

ETH Library Zurich

Taddeoli’s machine soared into the heavens, did a few pirouettes and then took a heart-stopping nosedive – the people on the ground gasped and applauded. Then Taddeoli steered the aircraft into another steep ascent and at an altitude of 400 metres, out of nowhere, there was an explosion: the plane disintegrated into a thousand pieces. Onlookers on that day, 24 May 1920, claimed to have seen the wings of the biplane, the cockpit, the propellers and the control surfaces fall into Lake Constance one by one. The two aviation pioneers were killed instantly, their bodies mutilated; it was later found that ‘the right side of [Taddeoli’s] skull had been sheared off’.

When the bodies were transported to the railway station in Romanshorn, hundreds of people formed a guard of honour to pay their last respects to ‘the deceased conquerors of the sky’, as the local paper Bote vom Untersee reported. To our modern ears, ‘conquerors of the sky’ may seem a strange thing to call the pilots of a plane that crashed, but in those days all pilots were heroes. Between Geneva and Lake Constance, between Basel and the Bündnerland, air displays and ‘Flugtage’ (flight days) were held at which air force pilots trained during the war demonstrated risky loop-the-loops and dangerous nosedives.

Seaplane on the Schützenmatt in Zug.

Zug Library

Air traffic authority, regulations and Swissair

However, the Romanshorn accident had far-reaching consequences for aviation in Switzerland. Since 1 April 1920, the Eidgenössische Luftamt (Federal Air Office) had existed as a government department, on the basis of the Ordnung des Luftverkehrs in der Schweiz (Regulation on aviation in Switzerland). This regulation gave aviation a legal basis and guidelines within which pilots were required to act. Just six months before Taddeoli’s fatal flight, Oskar Bider, another star pilot, had plunged to his death at a flight acrobatics show in Dübendorf.

It would be better, the newspapers were now saying, if, instead of these ‘death games’, air transport were to be operated for a more useful purpose. The company Ad Astra, founded by aviation pioneers Alfred Comte and Walter Mittelholzer, had organised the air show and felt compelled to give a detailed statement. In a letter to the newspaper Luzerner Tagblatt, the company claimed to have started out as a civil aviation company, in the year of the accident. But ‘partly as a result of inadequate information and partly as a result of many preconceptions that still existed’, there was not yet a need for regular air transport services in Switzerland. The company therefore had to use other avenues to generate its income – such as air displays. These flight days were also a good way to introduce the general public to the concept of aviation.

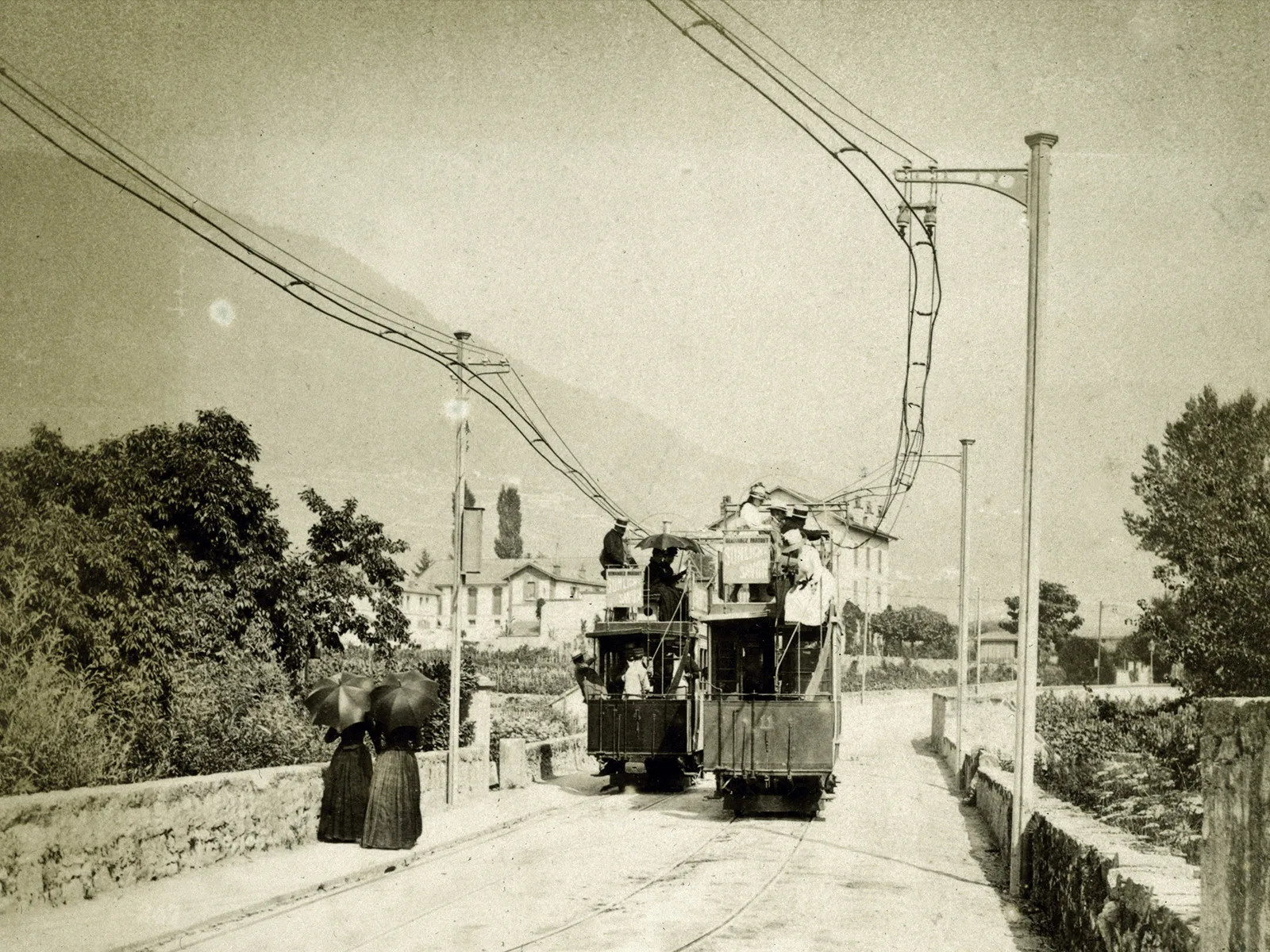

Ad Astra promised from then on not to perform artistic stunts such as dives. Instead, the company focused on offering sightseeing flights for paying passengers, using its seaplanes – civil aviation finally took off. This was a turning point in Swiss aviation history. Because of the accidents that killed Bider and Taddeoli, the use of aviation for civilian purposes became increasingly important. Ultimately, the founding of Swissair in 1931 was a late corollary of these terrible accidents.

Passenger flight on Lake Lucerne.

ZHB Lucerne

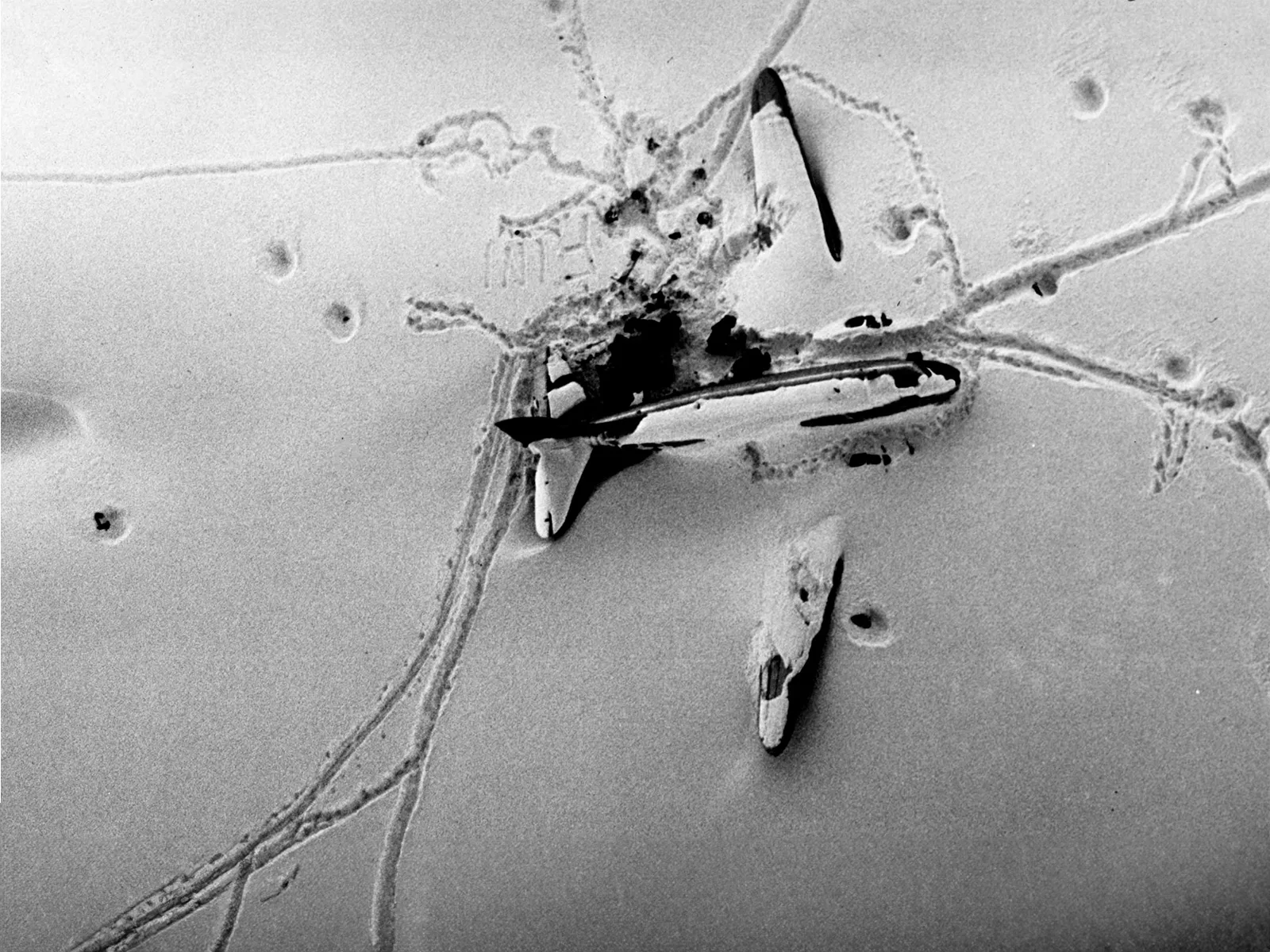

One of countless accidents: crashed aircraft of Lieutenant Tobler with the path of the downed aircraft marked out, 1923.

Swiss National Museum