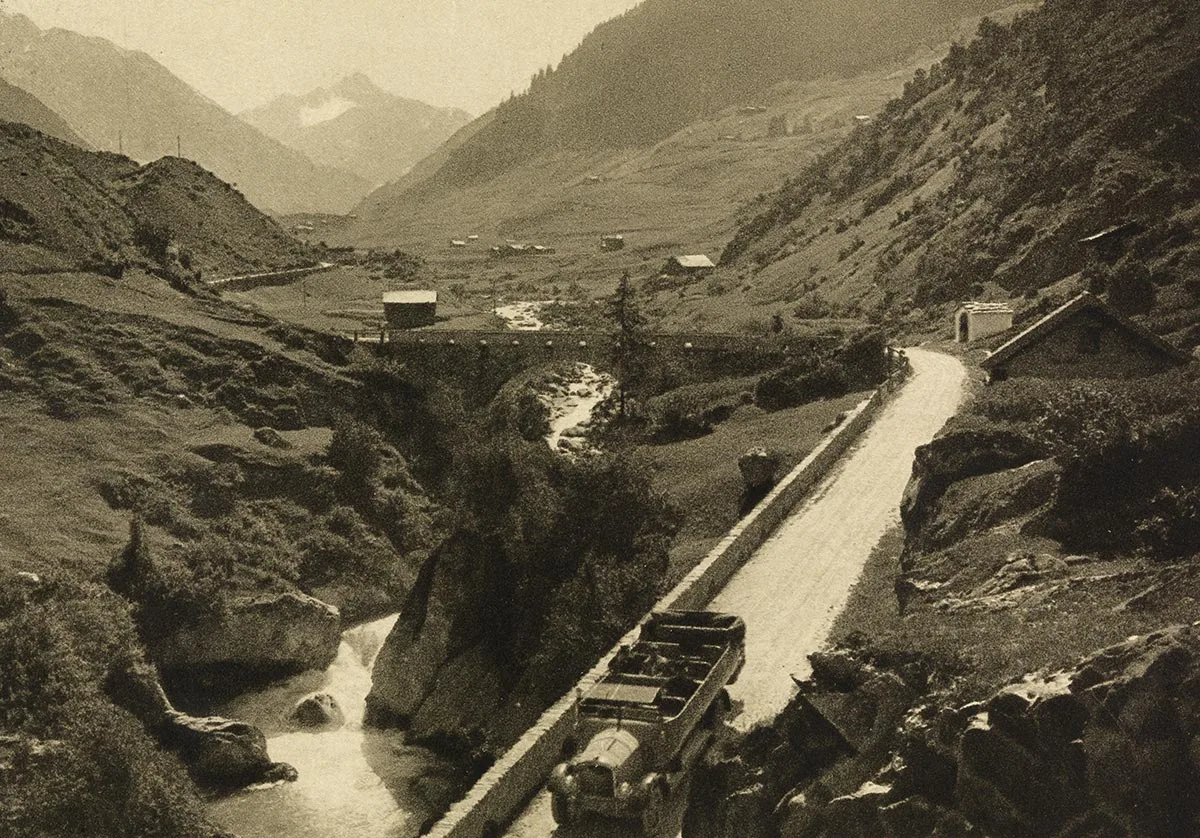

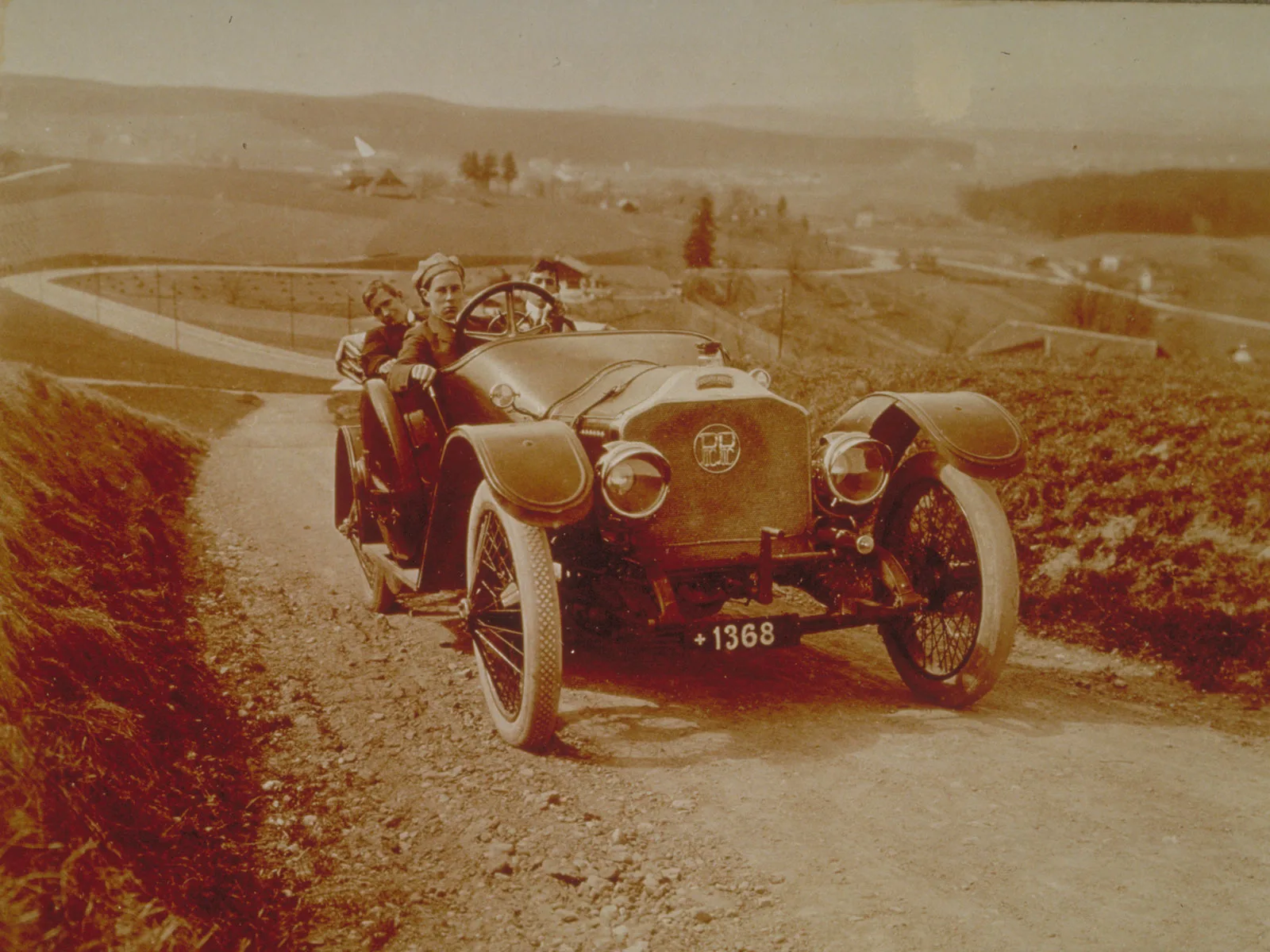

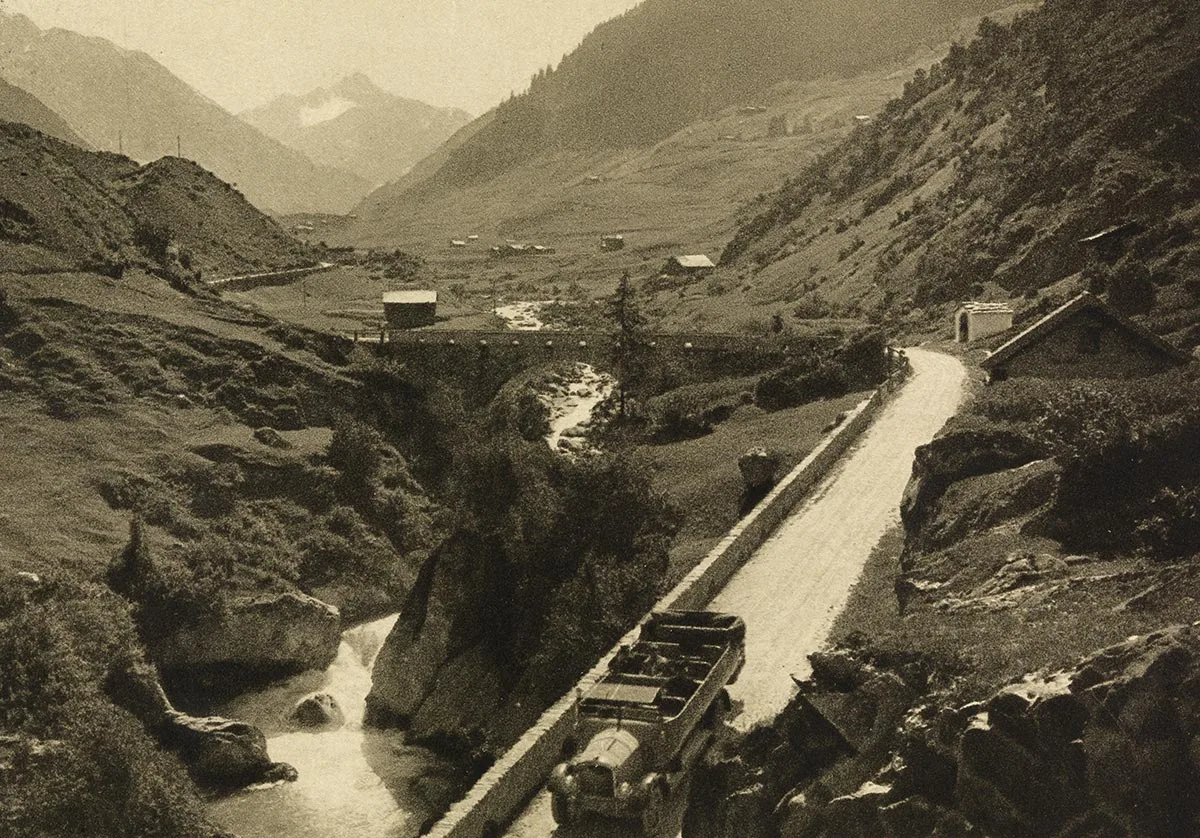

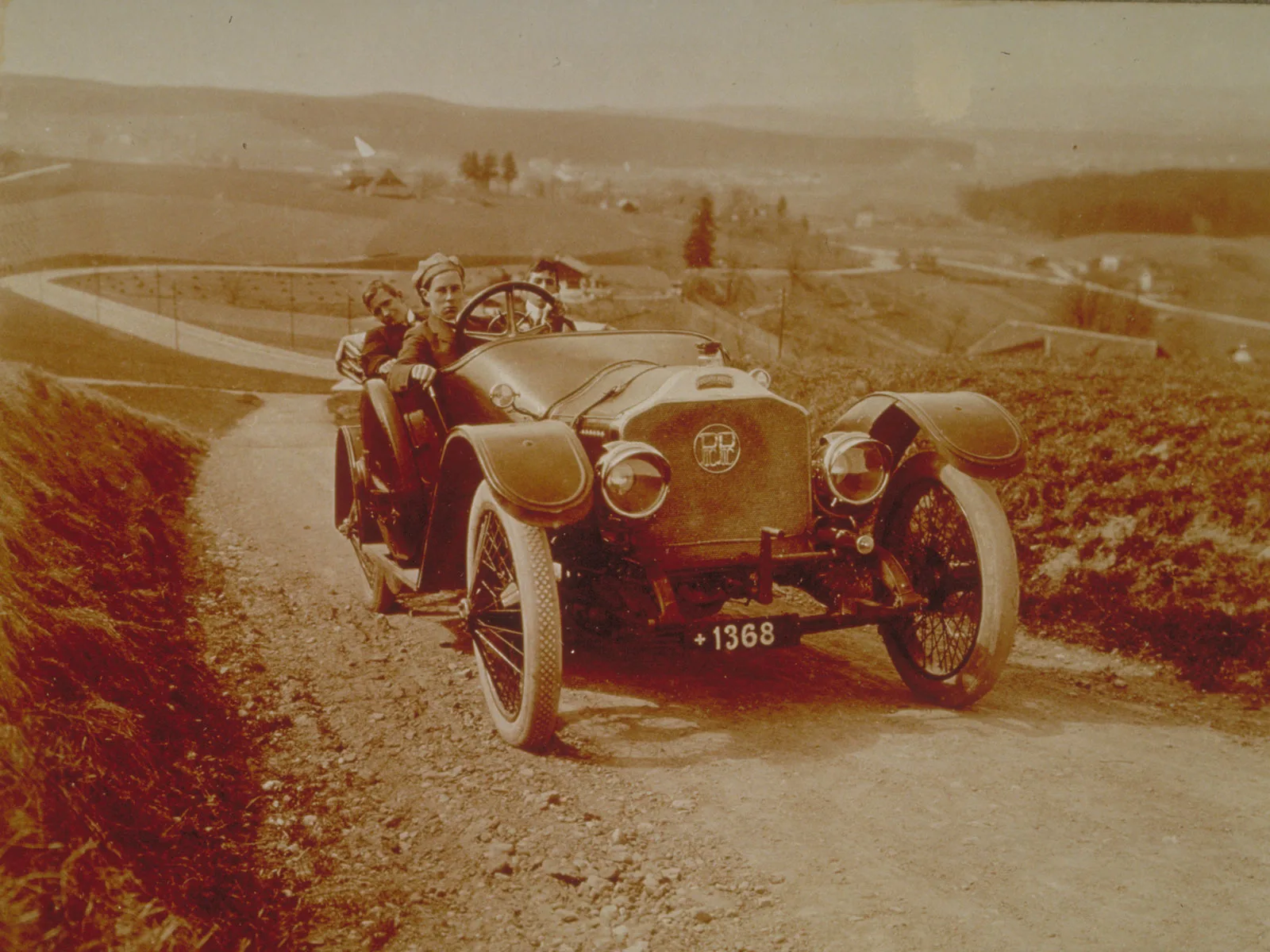

Graubünden: the canton that said no to the motorcar

Cars were banned in the canton of Graubünden from 1900 to 1925. It took nine popular votes to change that.

Expensive road maintenance

Cars were banned in the canton of Graubünden from 1900 to 1925. It took nine popular votes to change that.