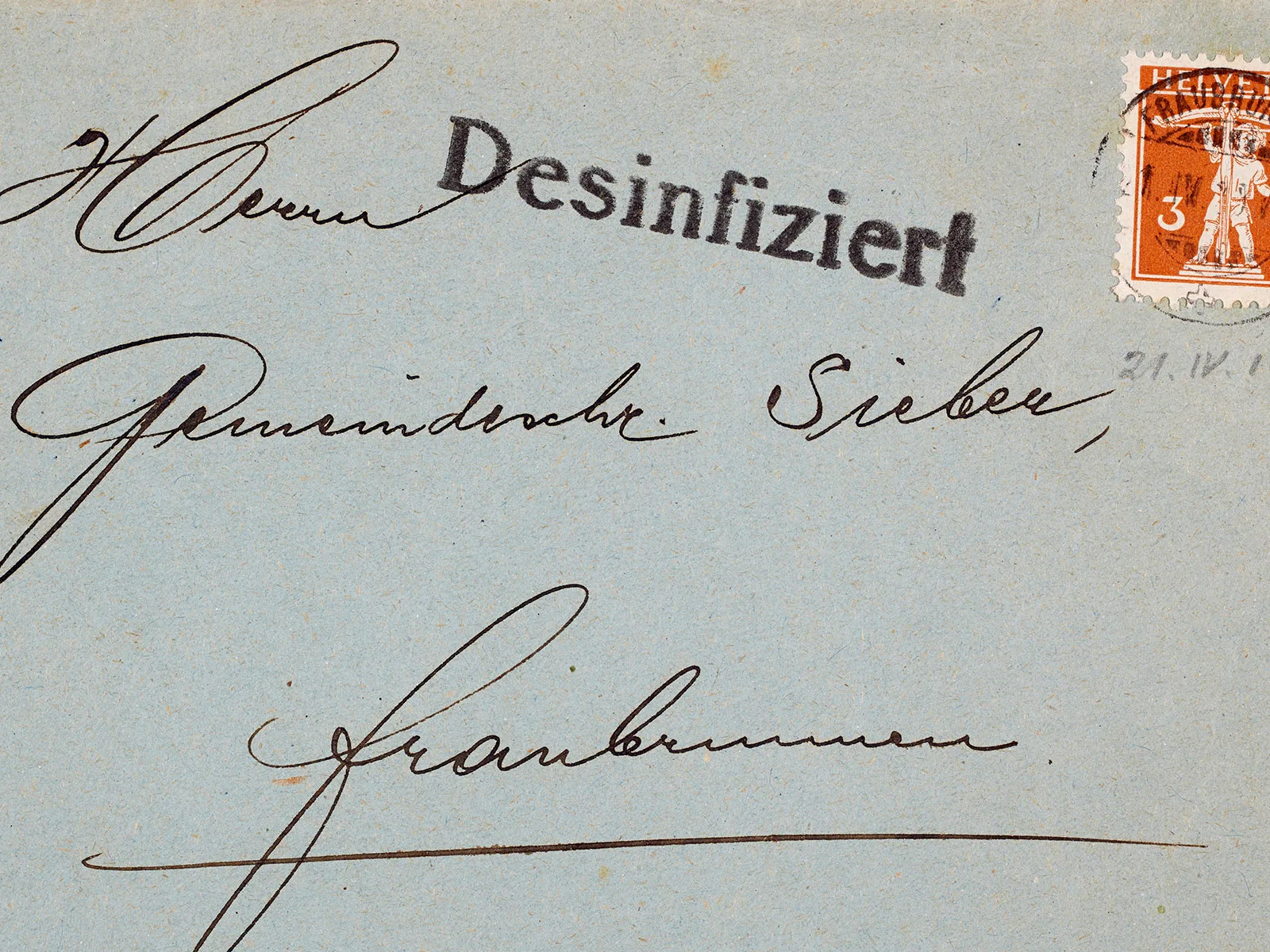

Disinfected letters

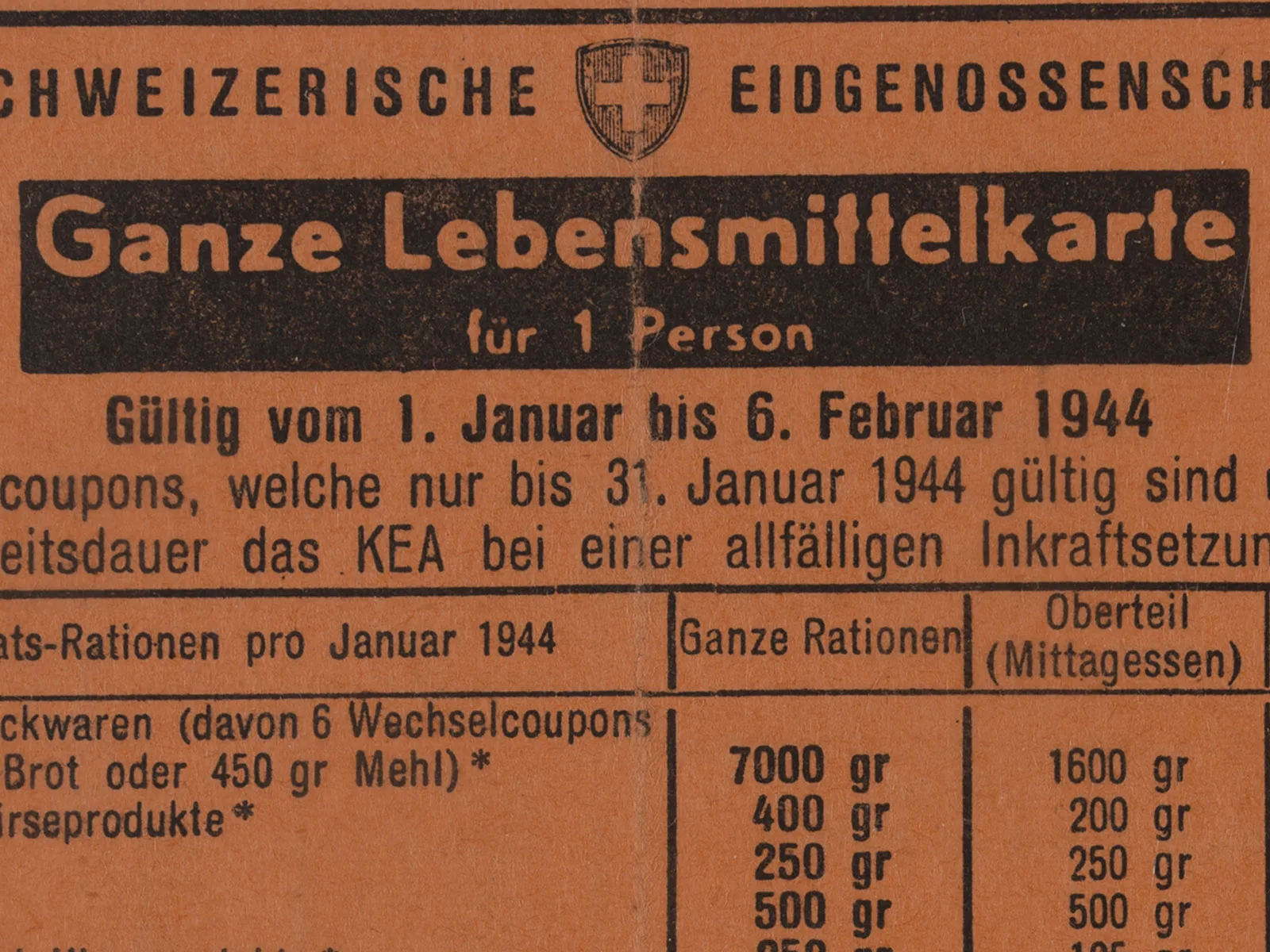

From cholera to coronavirus – epidemics have always had an impact on the postal service in Switzerland. A look back at the PTT archives shows how crisis situations were dealt with in the past.

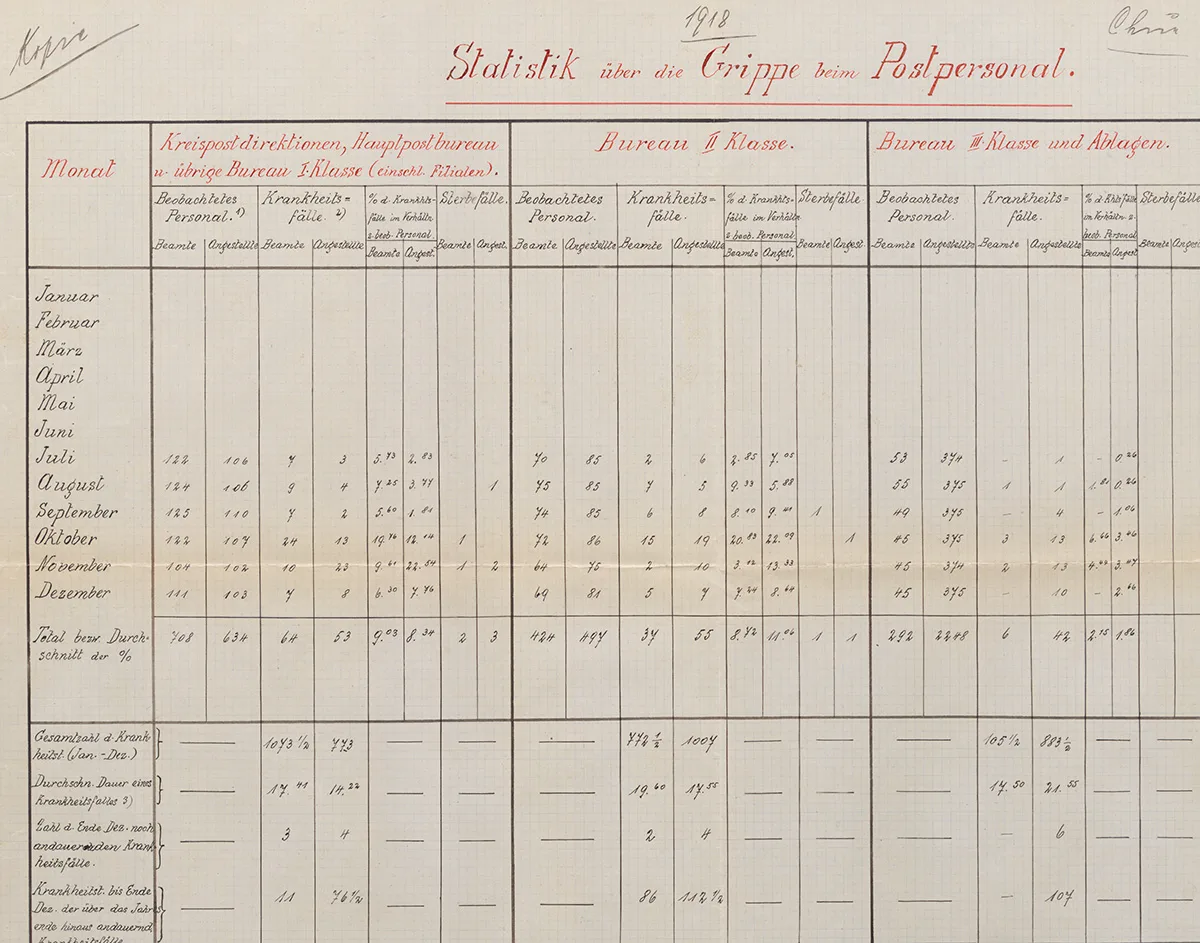

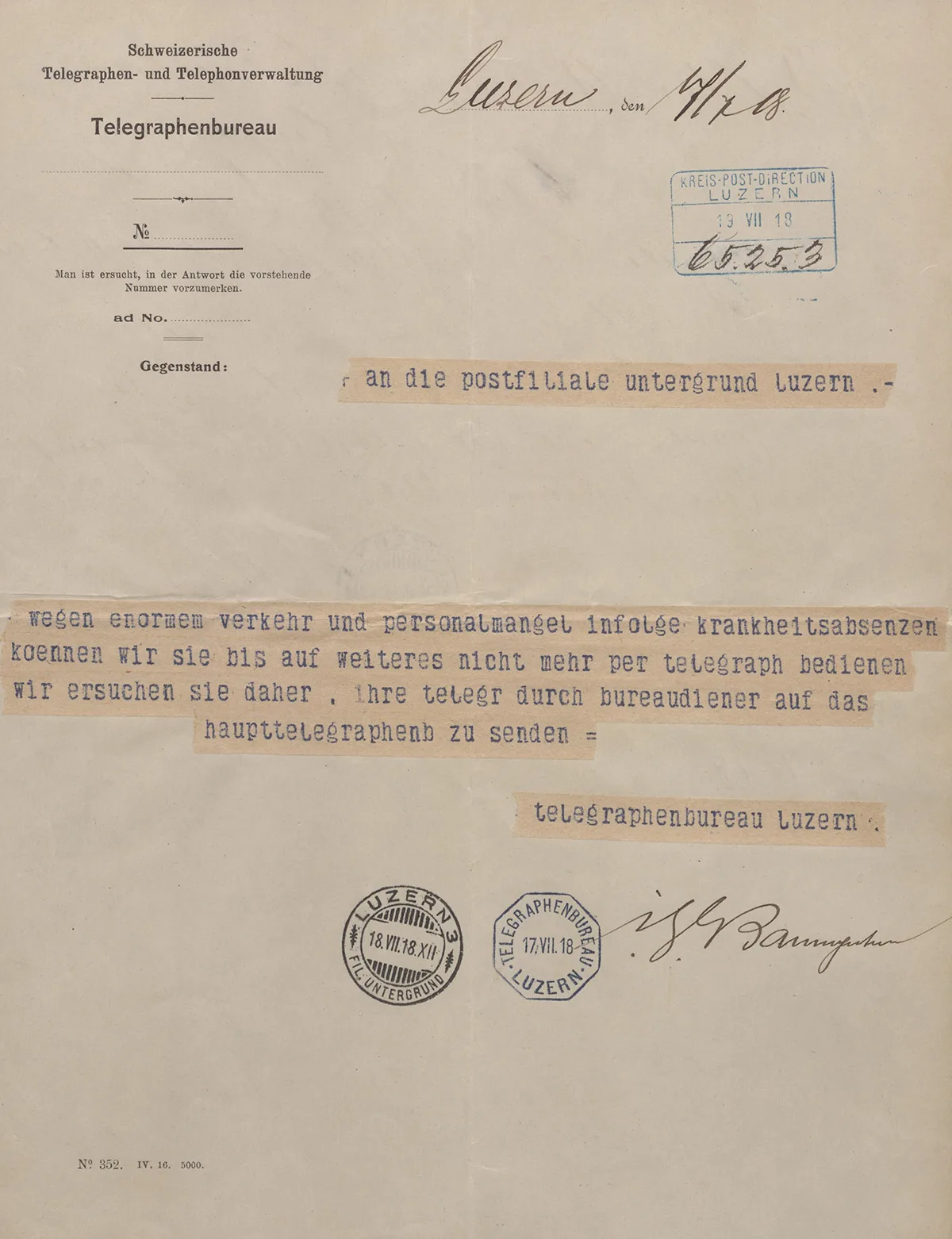

Powerless against the flu

Epidemics and creatures great and small