Food rationing in Switzerland

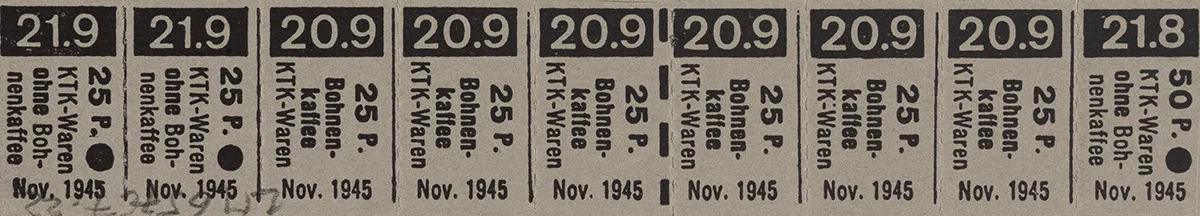

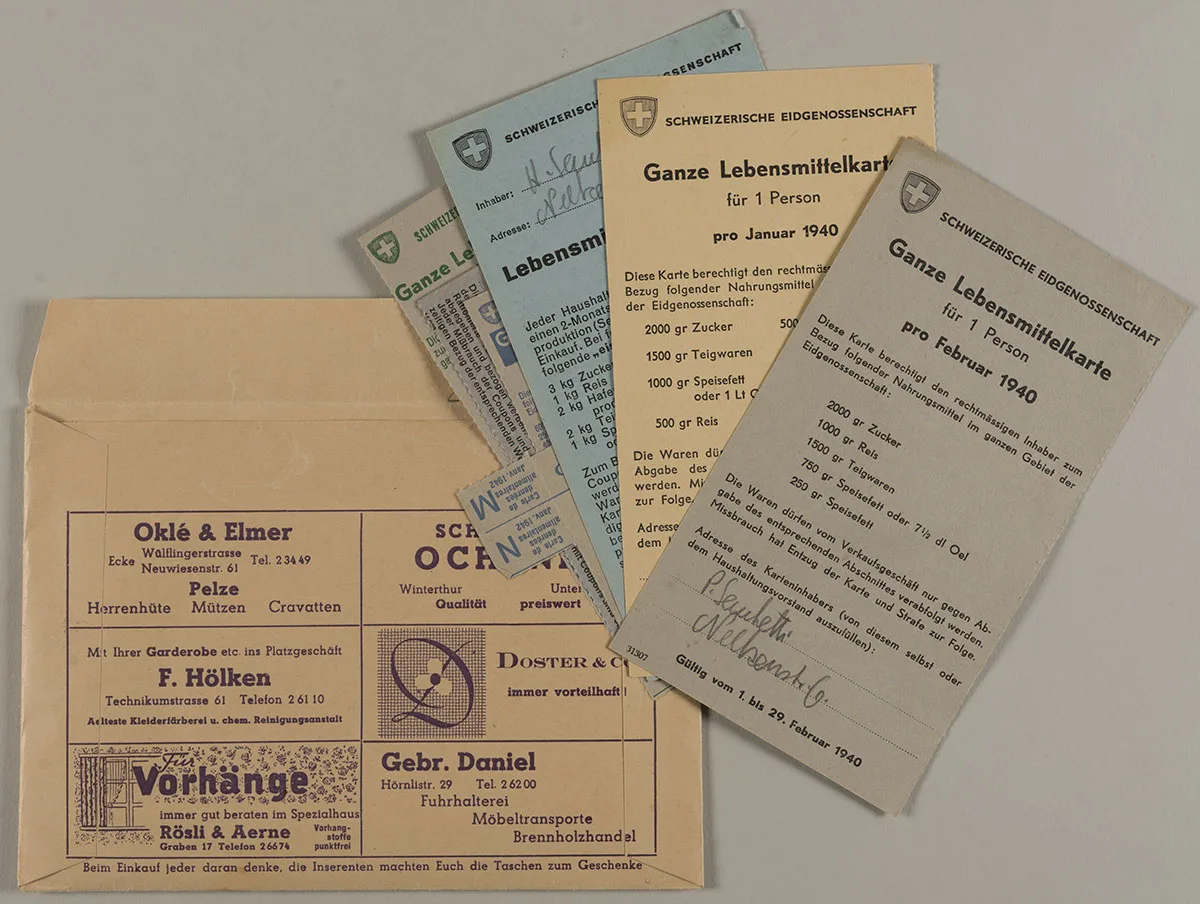

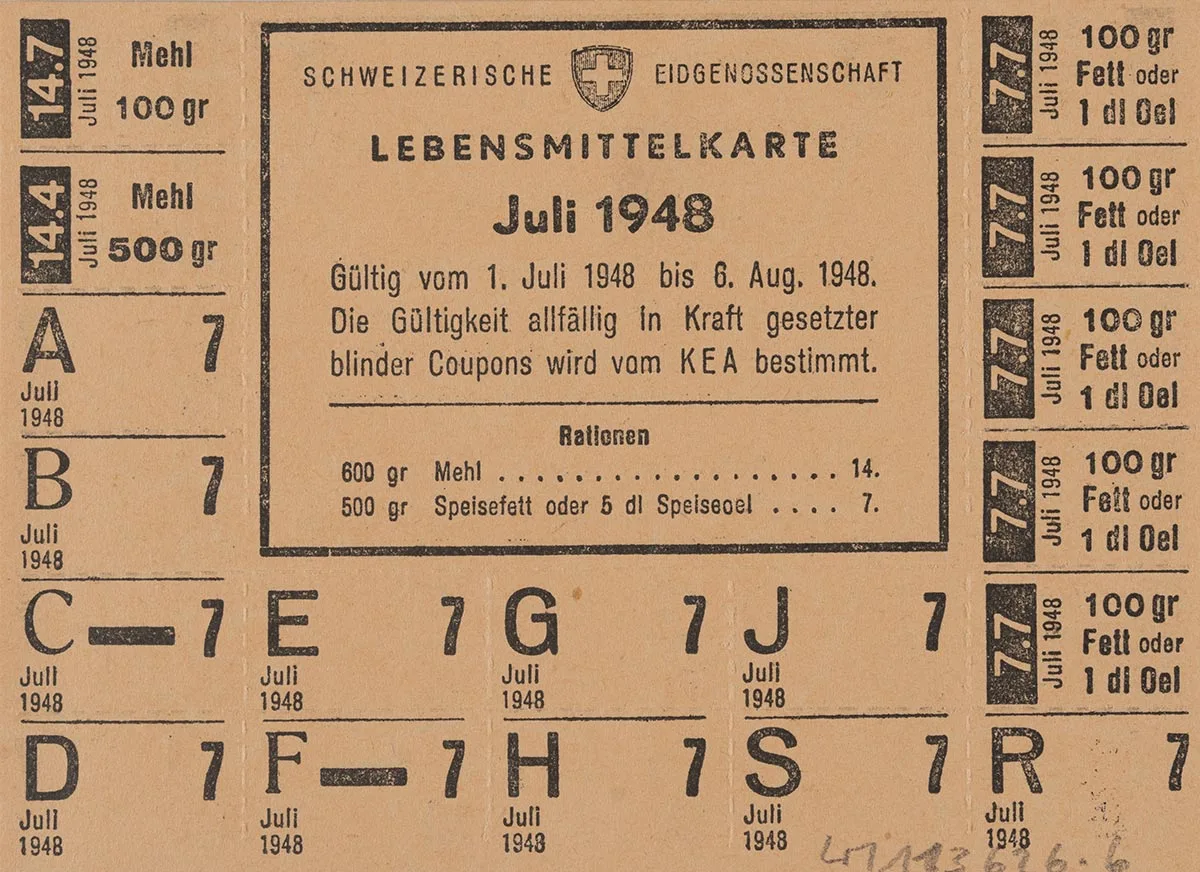

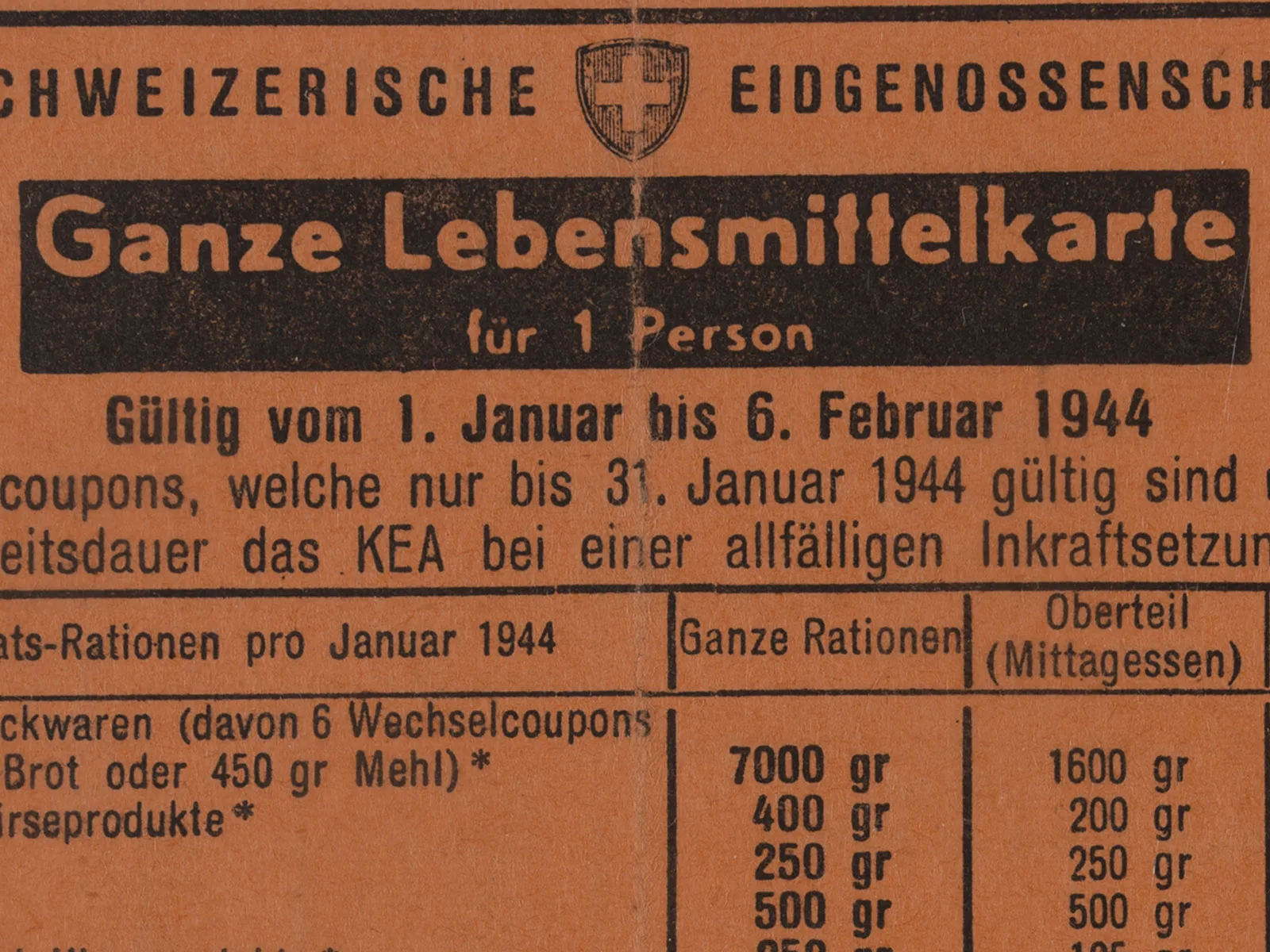

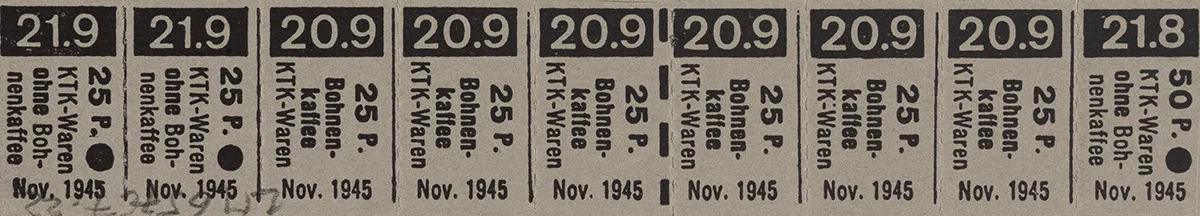

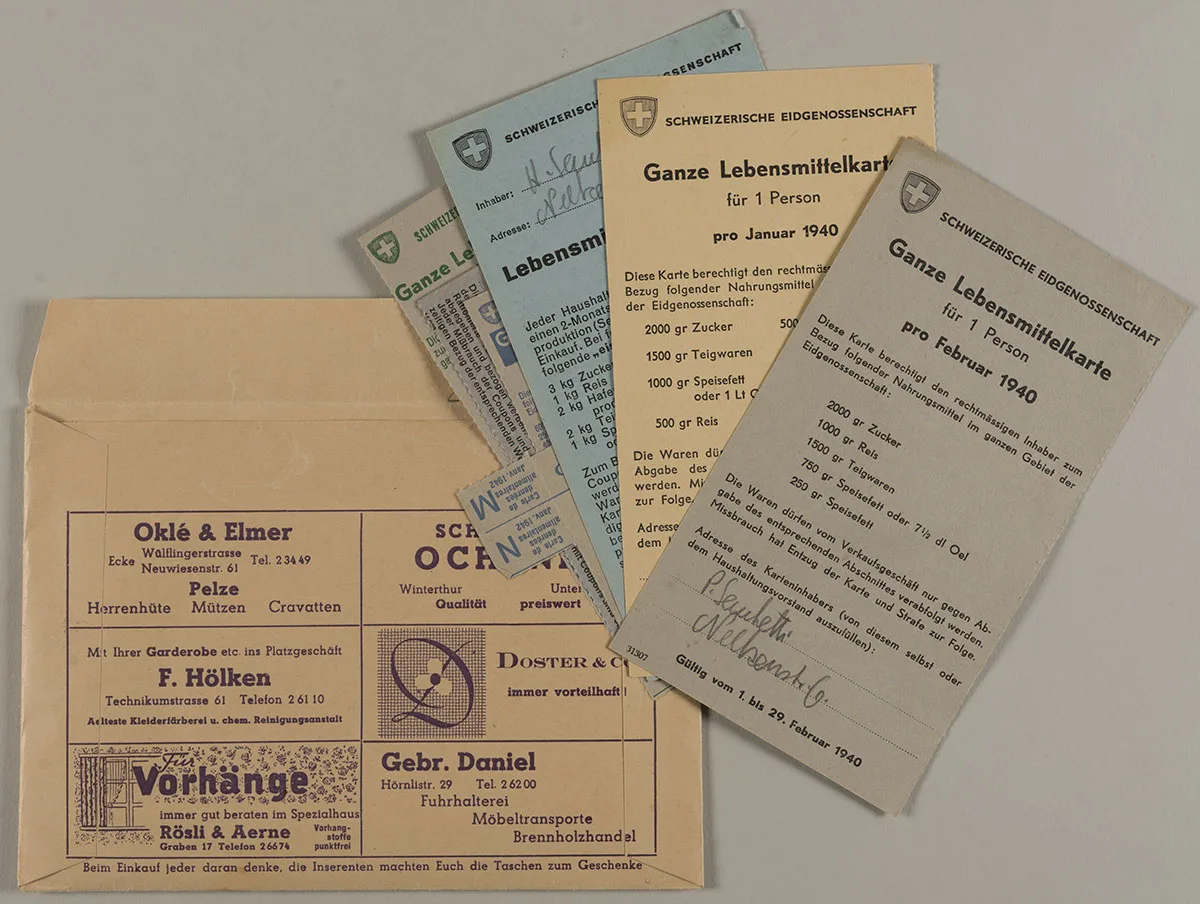

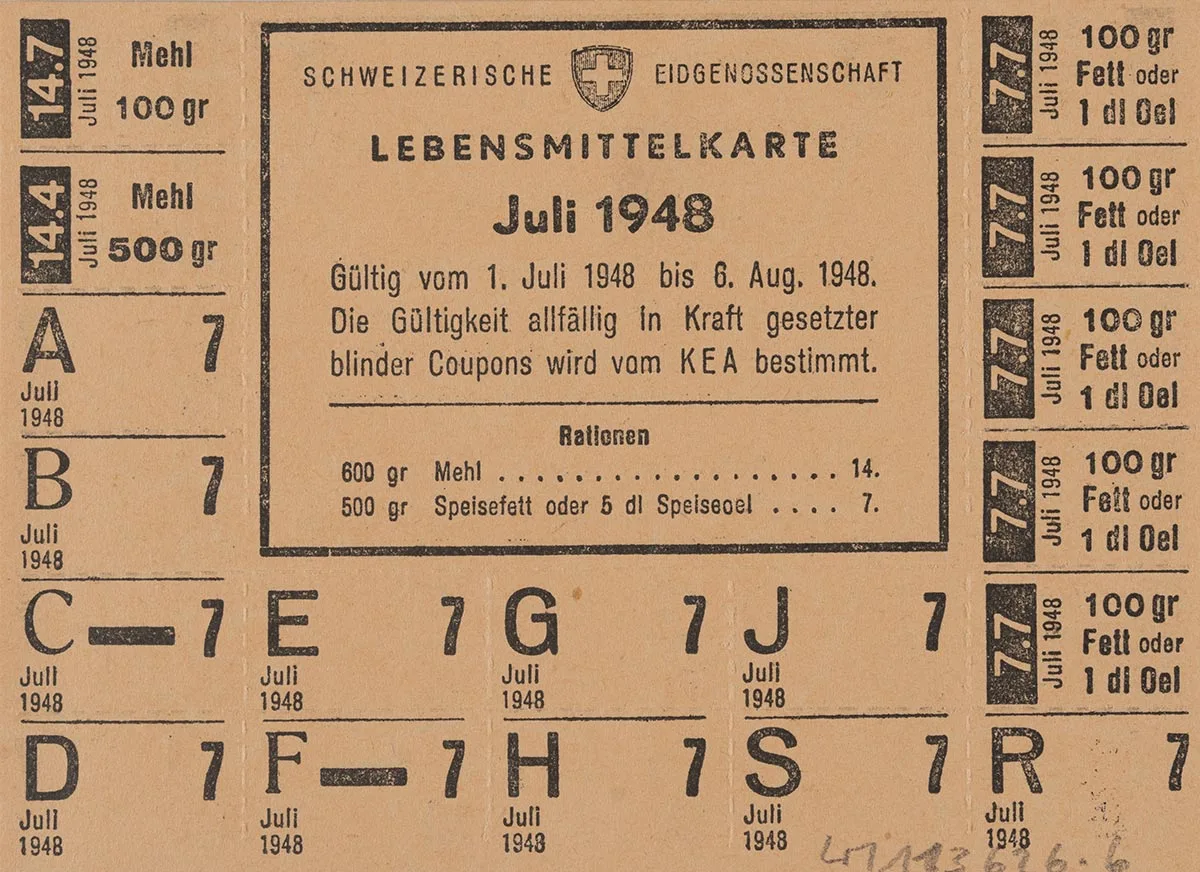

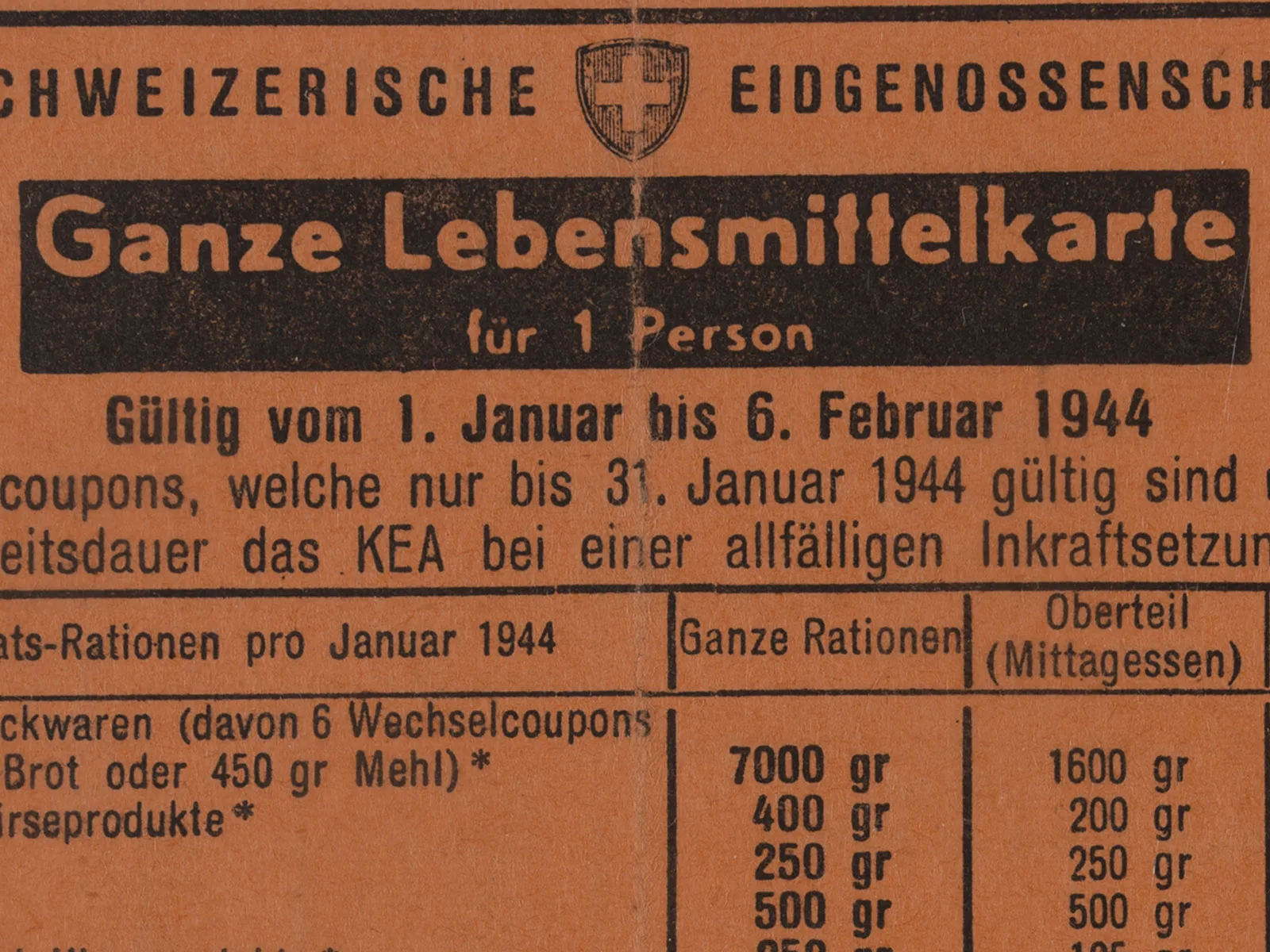

During World War II, you needed coupons to buy milk, coffee and sugar. A story from the non-digital world…

During World War II, you needed coupons to buy milk, coffee and sugar. A story from the non-digital world…