Shopping underground

On 1 October 1970, the Shopville shopping centre opened underneath Zurich’s Hauptbahnhof. The underground shopping arcade was a minor sensation.

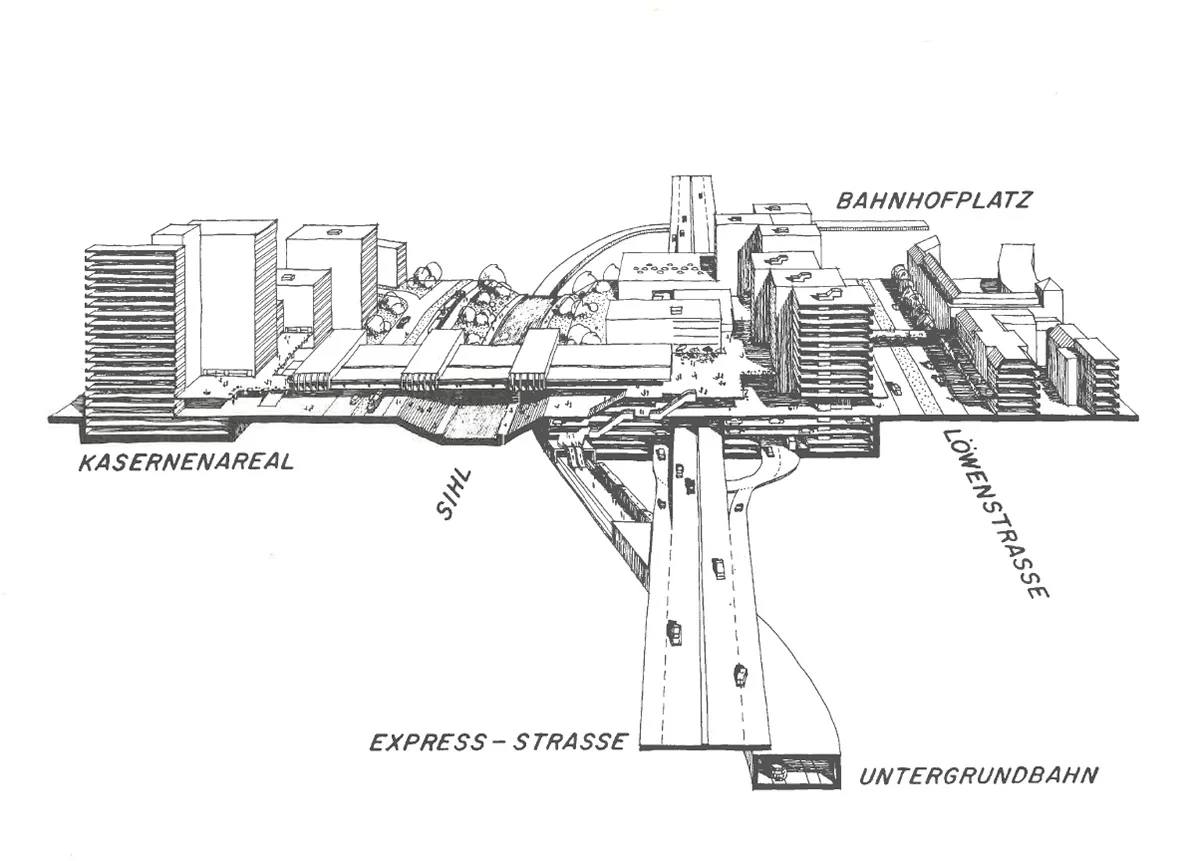

Going underground

A futuristic fossil

A shopping centre in the city centre

Competition and naming

TV report on the opening of Shoppville (in German). SRF

The reopening of the Bahnhofplatz

TV report about Shopville in Zurich, 1989 (in German). SRF