The Second War of Kappel

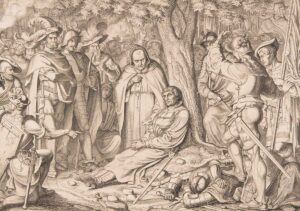

In 1531, two years after the legendary Milchsuppe (milk soup) incident, a battle took place at Kappel after all. The Protestants suffered a crushing defeat, and were forced to abandon their dreams of an exclusively Protestant Switzerland.

Surprise attack by night