The Sopraceneri fortress-builder

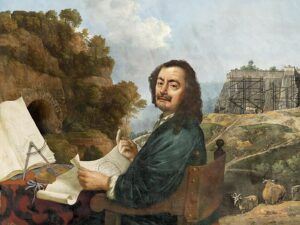

Pietro Morettini was the doyen of fortress-building. Originally from the south of the Confederacy, he worked for a number of different rulers and was held in high regard. Only in his homeland was he a relative unknown compared with his contemporaries.

Tesori — treasures from the Patriziato di Ascona archive

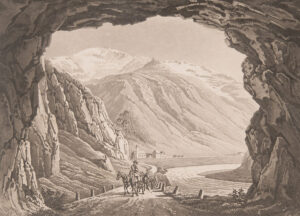

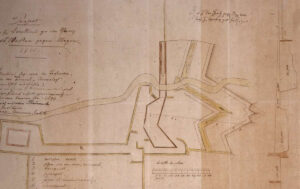

An exhibition in the Casa Vacchini in Ascona traces Pietro Morettini's work in the Ascona-Locarno region. It particularly features projects for rivers and lakes, and the rights of the nobility between the Maggia and Melezza rivers from 1703 to 1711. The display was organised by the Patriziato di Ascona heritage federation along with the Antenna Ticinese dei Verbanisti historical association. It runs until the end of February 2023.