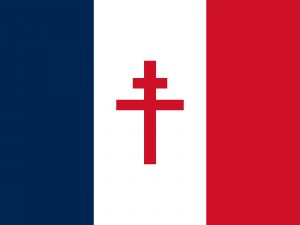

Swiss nationals in the Resistance

Thousands of Swiss people helped liberate France from German occupation. Hundreds of them were punished by Switzerland. They shall now be rehabilitated.

Geneva as a hub

Powerful allure

Documentary about Swiss nationals in the Resistance, September 1995 (in German). SRF

Great fear, tough sentences

Some empathy