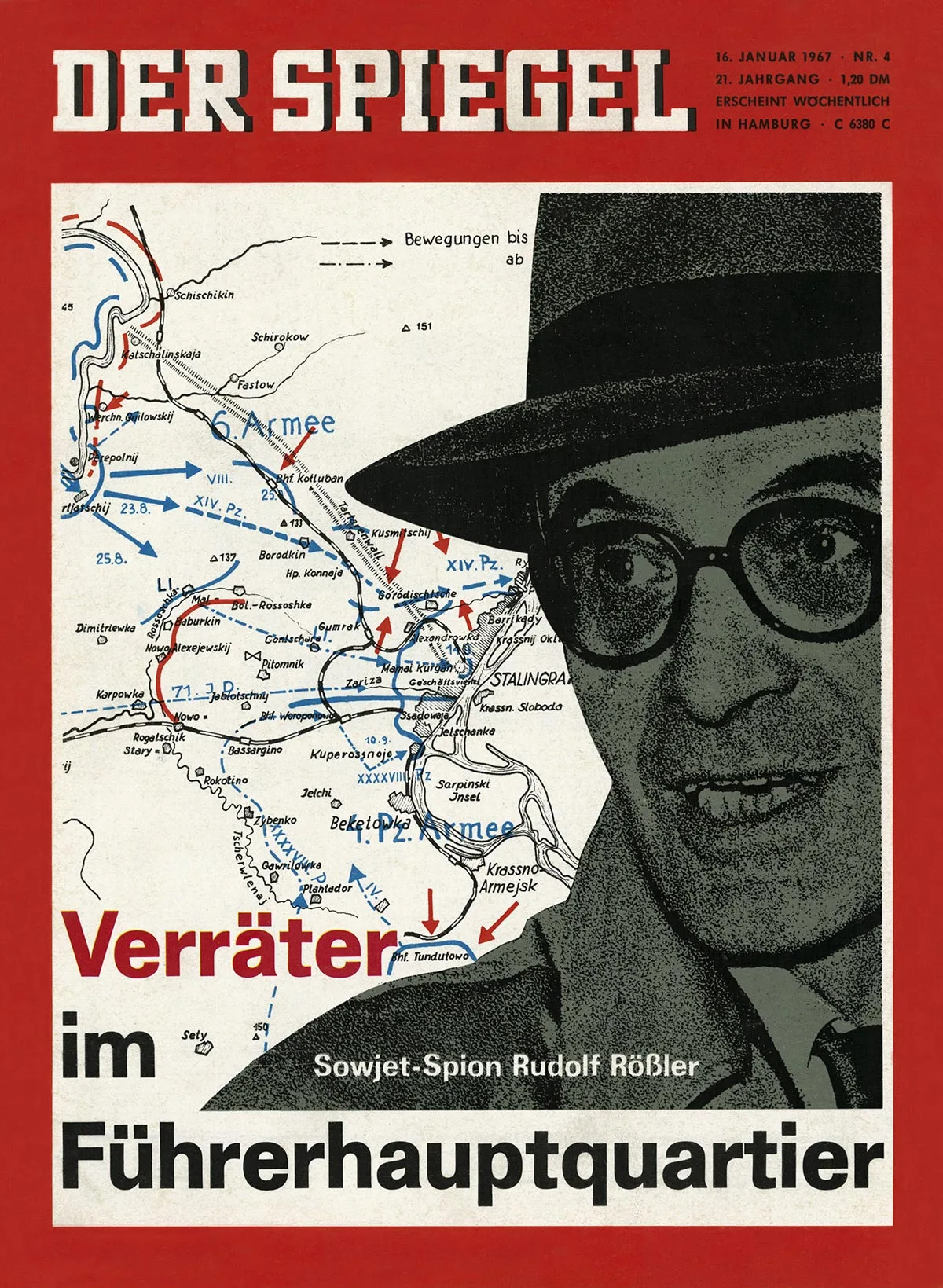

A spy called Lucie

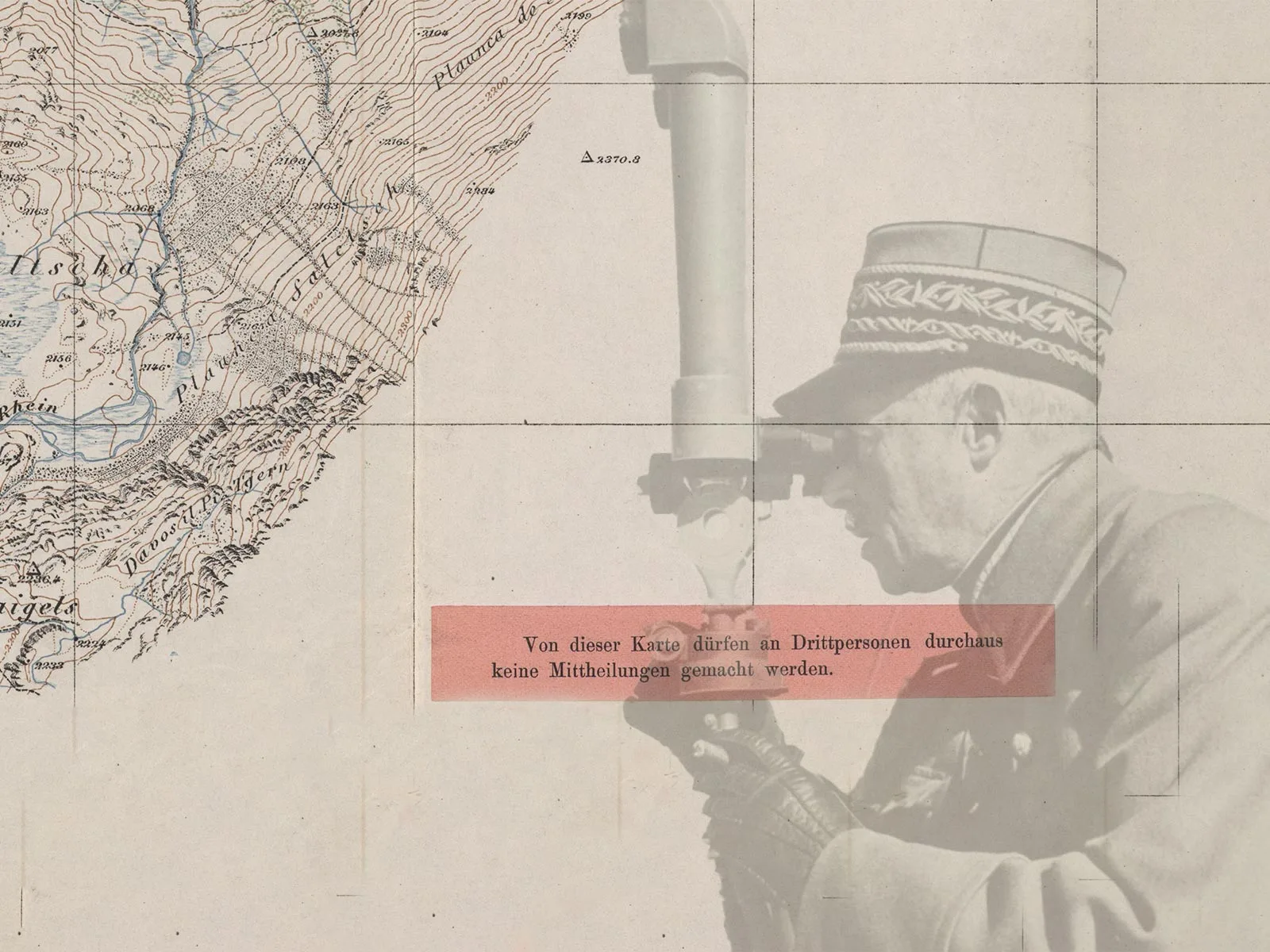

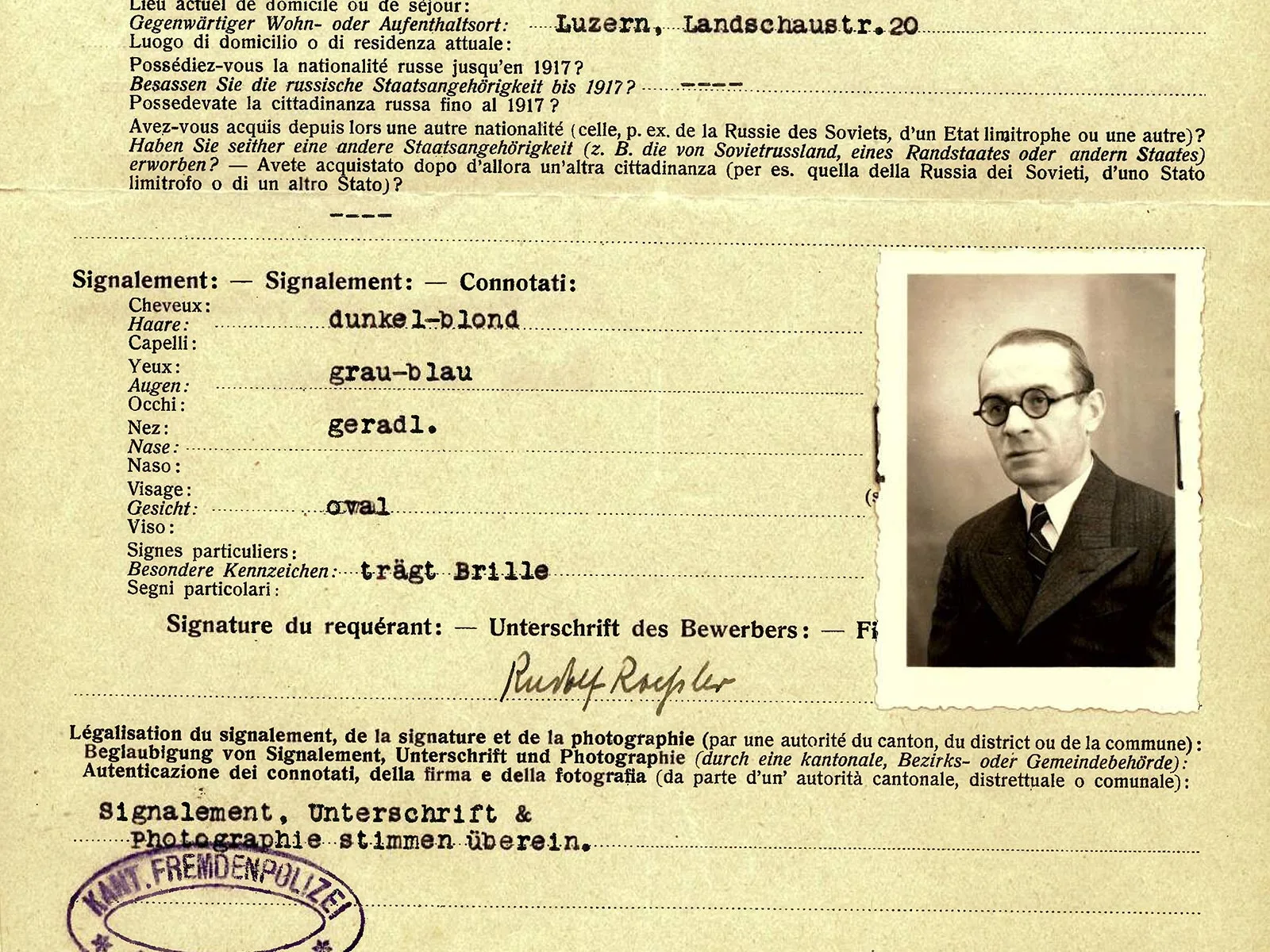

Rudolf Rössler was a mild-mannered journalist who ran a publishing firm in Lucerne. At the same time, he was supplying the Soviets with highly sensitive information straight from the Führer’s headquarters. The story of the master spy Lucie.

Dora, Rosa, Maud, Eduard and Jim