Museum zum Rathaus Sempach / Otto Schmid

Sempach 1940 – Souvenir des internés français

In 1940, General Guisan stood on the battlefield and called for resistance. Meanwhile, French internees wanted to sing the Marseillaise. Yet again, women were responsible for their welfare. ‘Allons les femmes de la patrie.’

‘The struggle that begins today will determine the fate of the German nation for the next thousand years,’ declared Hitler on 10 May 1940, issuing the order for the Wehrmacht to campaign west into France (the ‘Westfeldzug’). It was a ‘Blitzkrieg’. Just five weeks later, German troops marched into Paris. France signed the Armistice on 25 June.

Biel, 19/20 June 1940: During the night, 29,737 soldiers of the French army’s 45th Division crossed the Doubs, including 12,934 men of the 2nd Polish Rifle Division, who had continued fighting on the French side following the Wehrmacht’s invasion of Poland. In these June days, many of them have passed through the city of Biel.

mémreg

1000 inhabitants, 900 internees

Three days after crossing the border, 260 French internees arrived in Sempach. In a week and a half, their number increased to 900. The inhabitants of this small Lucerne town barely numbered a hundred more than that. Half of the internees could only be accommodated for a few days. ‘Around 400-500 men have now left,’ the town council noted on 6 July. The other 500 or so Frenchmen were probably there when the Schlachtjahrzeit service, commemorating the historic Battle of Sempach, was held on the hillside above the little town on 8 July.

Interned officers in front of the church in Sempach in summer 1940. The two with ‘kepi’ are French; the other three are Poles. Under an agreement with the Vichy government, the French were able to return to their homeland in January 1941. The Poles, however, had to remain in Switzerland until the end of the war.

Stadtarchiv Sempach / Caspar Faden

Complicated history(ies) à la française

A Wehrmacht officer wrote in his diary in June 1940: ‘We are living with two elderly Frenchwomen. This is their third invasion.’ Three conquests within 70 years. 1870, 1914, 1940. In 1871, 87,000 men of Bourbaki’s army crossed the border into Switzerland, fleeing the Franco-Prussian war. Now, in 1940, this third invasion had brought a good 42,000 men. On both occasions, sections of the French army sought refuge in Switzerland, in desperate need. They were disarmed, rendered harmless, housed, cared for.

In 1798, in the Helvetic Republic, the omens were different. France’s armies invaded Switzerland by force of arms. They brought to our country the achievements of the Revolution: liberty and equality, constitutional rule and human rights. Beyond price – but forced on us at the point of bayonets, by 35,000 men in Bern and 17,000 men in Nidwalden?

How much of their own complicated history were the French internees aware of when they were billeted in Sempach in 1940? And what did they know about the Battle of Sempach when, a few days after the doomed Battle of France, they were present as Guisan came down the hillside to the little town after the commemorative service and was officially welcomed? The assembled schoolchildren waved Swiss flags – and hundreds of French soldiers and officers formed a guard of honour for the General of the Swiss Armed Forces.

French and Polish troops crossing the border, 1940 (excerpts, no audio).

Swiss Federal Archives

Complicated history(ies) à la Suisse

The gist of Guisan’s address was: ‘Lage ist Auftrag’ – military jargon meaning the situation dictates what must be done. Throughout the entire six weeks of the Battle of France, the Federal Council remained silent. Then Pilet-Golaz finally made a statement on the radio: ‘Events are moving quickly. We must adapt to their rhythm.’ How were people to understand ‘adapt’ in 1940? A speech that muddied the waters rather than providing clarification. On the field where the Battle of Sempach had been fought, Guisan now went in the opposite direction, exhorting the Swiss people to resist.

Resistance? Why then had Guisan two days previously, on 6 July, dismissed 300,000 of the 450,000 soldiers in the Swiss army? Partial demobilisation just at the moment of greatest peril? A time-limited gesture of humility towards Germany? Standing on the Rütli on 25 July 1940, Guisan made everything clear: réduit, resistance, at all costs, even if it meant surrendering the Mittelland region to Hitler’s troops.

Service in 1940 commemorating the Battle of Sempach, the decisive snapshot. What looks like a random arrangement is very carefully staged: the priest of Sempach, Pastor Hans Erni, showing General Guisan the Schlachtbrief. The mythical narrative was given an elaborate religious slant.

Lucerne Central and University Library

A second and a first national anthem

The second one, the Sempacherlied, first: ‘Lasst hören aus alter Zeit’. Ostensibly a ‘sacred song’, the text is less so. ‘To the battlefield’, it says, ‘where the warriors with a muffled roar throw themselves into the frenzy of slaughter’. The murderous throng of Habsburg fighters is also mocked. A battle song from 1836 which, over the course of the 19th century, became more or less Switzerland’s second national anthem.

The Marseillaise, unquestionably the first national anthem of France, is just as sacred. The French internees asked whether they could be allowed to sing their anthem on the Sempach battlefield on 8 July 1940. The response from the authorities has not survived, but isn’t hard to imagine: not likely. Right at that moment, after the fall of France, to permit the singing of the French national anthem in a formal setting, and by French internees, would have been interpreted by Europe’s new overlords as supporting a signal of unwavering resistance – with unforeseeable consequences. Three months later, the French sang in Sempach anyway, but in a different context.

Ich bin ein Schweizer Knabe

Despite the war, the internees were offered something as part of the Schlachtjahrzeit celebrations: concerts, entertainment, dances. The admission fee for locals, 50 Rappen, benefited the soldiers from France. In autumn 1940, a world-class French ensemble of professional actors and musicians performed in the old Sempach Festhalle. Before internment, they had entertained the troops at the front; now, their interned comrades in several Lucerne municipalities, in Hergiswil, Buttisholz, Willisau and Sempach, were lining up to see them. The costumes were provided free of charge by the Stadttheater Luzern.

‘Last Thursday evening, our Festhalle was crammed full of internees and civilians’, said the report in the Sempacher Zeitung newspaper on 14 September 1940. ‘As announced in our last issue, the internee theatre group “D’Artagnan” performed for the general public, with a wide-ranging revue featuring 7 items.

The theatre director Marius Clémenceau, from Théâtre Antoine de Paris, was very impressive in his roles, and also deserves thanks and appreciation here for the entire arrangement. His closing number, “Ich bin ein Schweizer Knabe” (I am a Swiss boy), sung in shepherd’s shirt and short trousers, nearly reduced him to a coughing fit with its “k” and “ch”, but he showed himself yet again the consummate professional artiste, and the curtain came down to thunderous applause.’

Franz Joseph Greith (1799-1869), St Gallen, music teacher and composer. Numerous patriotic folk songs can be traced back to him, notably ‘Ich bin ein Schweizer Knabe’, and the Rütli song ‘Von ferne sei herzlich gegrüsset’.

Wikipedia

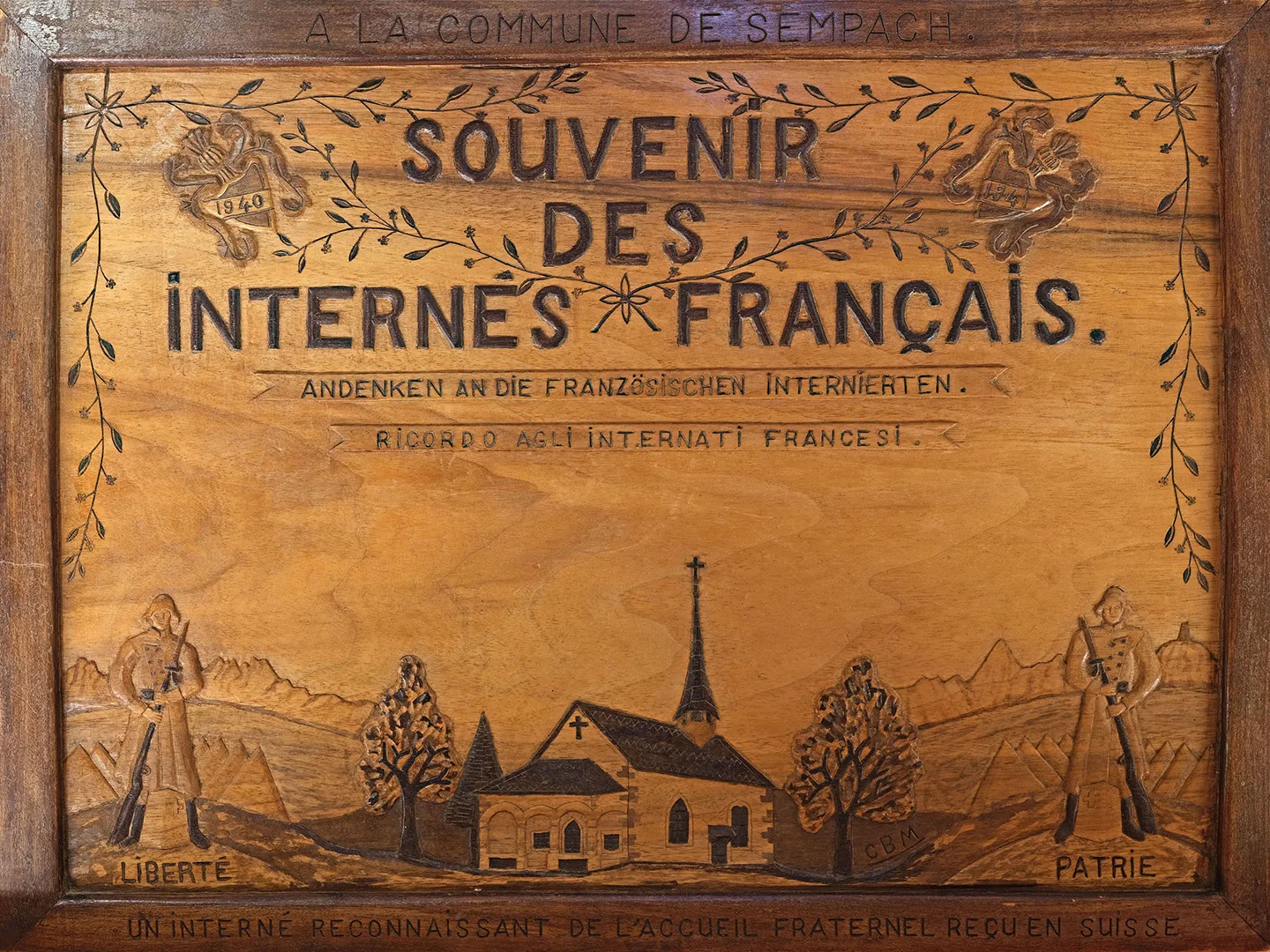

‘À la commune de Sempach. Un interné reconnaissant de l’accueil fraternel reçu en Suisse’ – To the municipality of Sempach. From an internee, in acknowledgement of our warm reception in Switzerland. 1940, 1941, Liberté, Patrie. The Schlachtkapelle in Sempach, guarded by two Swiss soldiers. (Schlachtkapelle, literally ‘battle chapel’, is a term used in Switzerland for a chapel dedicated to the memory of one of the battles of the Old Swiss Confederacy.) The impressive memento (not the only one of its kind) comes from CBM, C. Bailly, Maître, Rue Victor-Hugo, St. Claude, France.

Museum zum Rathaus Sempach / Otto Schmid

Military tribunal proceedings pursuant to art. 107

The ‘command of the local guard detachment’, however, was not impressed by the ‘thunderous applause’. Under threat of military prosecution, it was prohibited ‘to attempt to have contact with internees or to visit internees’ premises’. It was also forbidden ‘to give internees alcoholic beverages, whether free of charge or against payment’ and especially ‘to visit internees without permission; this applies in particular for female persons’, as the population was notified in the Sempacher Zeitung of 27 July 1940.

In 1940, around 500 French soldiers were interned in Triengen, Lucerne, including 30 or so Algerian Spahis. The Spahis wore a turban or fez, like the young woman pictured here, along with a bright red cloak. The exotic appearance of the Spahis aroused particular curiosity in the Suhrental.

Private archive of Alois Fischer / Franz Kost

Allons les femmes de la patrie!

There is no mention of a ‘jour de gloire’ among the women of Sempach. They saw straightaway what needed to be done. ‘These poor, fleeing people, so dreadfully afflicted by the war, lack so many of life’s necessities. Their feeding is taken care of, but who is making sure they are adequately clothed?’, the women are recorded as asking. The list of effects the internees needed was long: 230 pairs of underpants, 120 pairs of socks, 50 shirts, 200 pairs of shoelaces, 140 washcloths, 65 handkerchiefs, 70 woollen blankets, 130 pullovers and much more.

Interned Poles while away the time in summer 1940 in front of the former Zehntenscheune (tithe barn) in the upper town of Sempach.

Stadtarchiv Sempach / Caspar Faden

Women too are stronger together, so they joined forces: the Samaritan association, the Marienverein, the women’s union, the mandolin club and the traditional costumes group. ‘A door-to-door collection would be the most effective solution,’ they agreed. ‘Even timber would be appreciated. Those who have nothing to give in kind could perhaps support the collection with a monetary donation.’

The undertaking was organised with military precision: each small group of women took on a residential area or a street of houses. At least some of them should be named here, representing all those who helped: Postmistress Lieb and Miss Josy Brandenberg: Felsenegg, Rosenegg and Seesatz / Miss Martha Schüpfer and Miss Nina Steger: Rainhöfli as far as and including Schürmann, Honrich / Miss Anna Schifferli and Miss Marie Weber: bottom row of Stadtstrasse as far as Meierhöfli – and so on.

The women not only collected clothes for the internees, but also put them back in wearable order. They kept records of this, as any proper women should. 919 items of clothing were washed, 1,066 patched and mended – voilà!

What remains

A certain Paul B., whose surname can no longer be made out, perhaps an NCO, is believed to have been housed as an internee for seven months, from late June 1940 until after New Year, in the house of teacher Marie Helfenstein at Stadtstrasse 24 in Sempach. Did he just forget to take his canteen with him, or did he leave it as a keepsake for Marie Helfenstein when he left on 24 January 1941?

Canteen of a French internee in Sempach: the material value is minimal, the sentimental value incalculable.

Museum zum Rathaus Sempach / wapico

Under the agreement between the governments in Berlin and Vichy, the French returned home after New Year 1941. One of them, Jean, was housed in Sempach with the Zürcher family, the local butchers. – About 30 years later, on a trip to Switzerland he visited Sempach and heard that Zürcher’s youngest child, Walter, was just getting married to his Theres. The former internee rushed to Kirchbühl, burst through the ranks of guests, embraced the bridegroom and beamed: ‘Quel joli garçon!’ The young man had no idea what was happening – until his mother appeared and exclaimed: ‘Jeses, das isch jo de Jean!’ Local history becomes world history.